31

Shot of the Month – October 2017

If you love color, check your calendar and your compass as it is likely that Mother Nature is putting on a glorious show somewhere near you. In the northeast of the US, the best time is in the autumn with the fall foliage. Here in Washington state there is a lovely explosion of color in the meadows near Mount Rainier each summer. How good is the display? Well, Bob Gibbons, in his book, “Wildflower Wonders: The 50 Best Wildflower Sites in the World” lists Mt. Rainier as the #1 location to visit!

If you love color, check your calendar and your compass as it is likely that Mother Nature is putting on a glorious show somewhere near you. In the northeast of the US, the best time is in the autumn with the fall foliage. Here in Washington state there is a lovely explosion of color in the meadows near Mount Rainier each summer. How good is the display? Well, Bob Gibbons, in his book, “Wildflower Wonders: The 50 Best Wildflower Sites in the World” lists Mt. Rainier as the #1 location to visit!

The best time to see the show? Well, Mother Nature is an artist and is not fond of strict schedules and the like. She creates as the mood suits her. This mountain park is divided into three zones by altitude. Dense forests cover the low to mid-elevations of the park from 2,000 to 4,500 feet. The cool, shady conditions found here suit wildflower species that won’t be found higher up. These flowers tend to bloom earlier in the summer. Next, we have the subalpine zone from 4,500 to 6,500 feet. The subalpine zone often has the most impressive wildflower displays because the growing season is so short here. Snow can linger in the subalpine meadows into June and even July — so the flowers need to burst out as quickly as they can before the snows return. Climbing higher is the alpine zone from 6,500 feet to the summit of the mountain. There are a few hearty flowers in this zone but it is not where you want to be for the most color. (source)

The “peak” bloom for subalpine wildflowers is very dependent on weather and precipitation patterns. Typically, most flowers will be blooming by mid-July and by early August the fields can be bursting with color. But some years the peak happens in late June. Also, climate change is starting to impact the timing and seems to be shifting the bloom to earlier in the summer. So far I have found the 1st or 2nd week of August to be the most colorful.

What will you see? Mt. Rainier has hundreds of species of wildflowers — a cornucopia of blues, purples, oranges, reds, whites, greens, pinks, and on and on. In this quiet, peaceful sunrise image above we look over a long sloping meadow dominated by sub-alpine lupines (purple) that leads to snow-covered Mt. Rainier off in the distance. There are also dashes of red (Scarlet Paintbrush) and pink (Pink Mountain Heather). Come on a different day, at a different time of day, on a different trail and you can see a completely different color palette. Here to the right is a rambunctious burst of afternoon color dominated by yellows (Broadleaf Arnica and Bracted Lousewort)) and reds (Scarlet Paint Brush) amongst others.

whites, greens, pinks, and on and on. In this quiet, peaceful sunrise image above we look over a long sloping meadow dominated by sub-alpine lupines (purple) that leads to snow-covered Mt. Rainier off in the distance. There are also dashes of red (Scarlet Paintbrush) and pink (Pink Mountain Heather). Come on a different day, at a different time of day, on a different trail and you can see a completely different color palette. Here to the right is a rambunctious burst of afternoon color dominated by yellows (Broadleaf Arnica and Bracted Lousewort)) and reds (Scarlet Paint Brush) amongst others.

The canvas changes by the hour.

If you do dig your hiking boots out of the closet to take in a mountainside color exhibition do take great care. Mountain wildflowers are exceptionally fragile. Each step you take off the trail can crush 20 plants. Even if a plant survives the weight of your footstep its growth can be stunted for years!! Stay off the artwork!!

A few resources:

Here is a good article on planning a trip to Mt. Rainier to see wildflowers.

A nice collection of hikes on Mt. Rainier to see wildflowers.

A handy wildflower guide of Mt. Rainier.

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikkor 17-35mm (@17mm), f/16, 1/10 sec, ISO 200, EV -0.666

30

Shot of the Month – September 2017

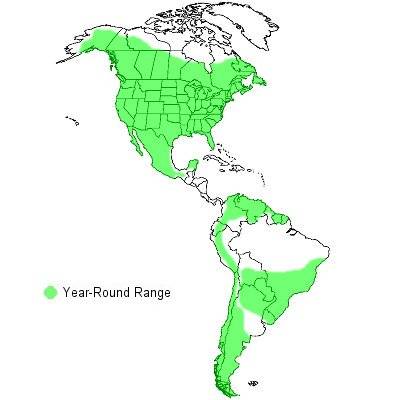

Despite all my early morning gallivanting in the woods over the years I had never seen a Great Horned Owl (GHO). I find this even more astounding having recently learned that the GHO is THE most common owl in America. If you live in North America there is probably a Great Horned Owl family living in a tree not far from your house. These owls are incredibly adaptable and can live just about anywhere and can be found from the Arctic to South America.

Despite all my early morning gallivanting in the woods over the years I had never seen a Great Horned Owl (GHO). I find this even more astounding having recently learned that the GHO is THE most common owl in America. If you live in North America there is probably a Great Horned Owl family living in a tree not far from your house. These owls are incredibly adaptable and can live just about anywhere and can be found from the Arctic to South America.

The GHO is a big bird – it is the second heaviest owl in North America and as such is a fierce predator and can take prey much larger than itself. These owls normally begin nesting weeks or even months before other raptors – here in Washington State GHO chicks typically appear in February! Keeping eggs warm during the winter is very difficult. Why take such a risk and not just wait till later in the spring like most birds? Well, given the large size of the species, the chicks need more time to grow and develop into young adults. Also, young GHOs must master complex hunting maneuvers. By hatching early in the spring they maximize the time available to practice flying and improve their hunting skills while the weather is mild and prey is abundant (source).

GHOs typically nest in trees such as cottonwood, juniper, beech, pine, and others. They usually adopt a nest abandoned by another large bird, but they also use cavities in live trees, dead snags, deserted buildings, cliff ledges, and human-made platforms.

Fun fact: As a rule, no owl species builds its own nests. I didn’t know that, either. (source)

This year I went from never seeing a GHO owl to having the good fortune of finding not one, but two GHO nests. In Nisqually NWR (an hour south of Seattle) I found an owl family with three chicks. As you can see, in their youth they are adorable fluff balls. The Nisqually family was raised in a cavity in the tree though from time to time the chicks would come out and stand on this fork in the trunk and give us a view. Here to the right, you can see one of the rare moments where all three chicks can be seen at once.

In Nisqually NWR (an hour south of Seattle) I found an owl family with three chicks. As you can see, in their youth they are adorable fluff balls. The Nisqually family was raised in a cavity in the tree though from time to time the chicks would come out and stand on this fork in the trunk and give us a view. Here to the right, you can see one of the rare moments where all three chicks can be seen at once.

In the Skagit Wildlife Area (about an hour north of Seattle) I found this family on the left with two chicks.

In the Skagit Wildlife Area (about an hour north of Seattle) I found this family on the left with two chicks.

Despite the wide distribution of these wonderful owls, we rarely see these denizens of the night. Many people do hear their classic owl Hoots either early in the morning or at night.

If you are fortunate enough to find a GHO nest do take care. GHO adults, monogamous for life, are dedicated parents and both males and females will stand guard over the chicks. The male typically roosts nearby, out of sight, but from a location where he can watch over the nest. The female alone incubates the eggs while the male will go off to hunt and bring food back for his mate. GHOs will defend their nest with great vigor and they have been known to attack humans that wander too close to a nest.

You’ve been warned…

Great Horned Owl Range (Source)

Until next month

Nikon D500, Nikon 600 mm f/4, 1/500 sec, ISO 2200, +2 EV

31

Shot of the Month – August 2017

To be honest, I am not big fan of Canada Geese. As a photographer I am drawn to capturing species that are elusive and rarely seen. This ubiquitous waterfowl seems to be EVERYWHERE which, unfairly or not, bores me. Also, visually, I don’t find them all that interesting. Black and white with a side of Bleh.

On many an occasion I have been in the field and detected movement and quickly readied my camera. But once I saw those common features, a quick sigh would follow, “Just a Goose,” and a feeling of chagrin at the false hope of something special.

They are my avian Rodney Dangerfield — they get no respect. (For the uninitiated, Rodney Dangerfield was a comedian that made a very successful career providing numerous examples of how no one respected him: “When I was born, the doctor came out to the waiting room and said to my father, ‘I’m very sorry. We did everything we could but he pulled through.’ ” Here is a small sample. Rodney is also famous for his roles in Caddyshack, EasyMoney, and Back to School).

But I digress.

The point is, I never imagined that I would post a Shot of the Month featuring a Canada Goose.

But then this lovely little scene happened. Usually it almost impossible to properly expose a Canada Goose due to the strong contrast between their black and white features. On this cloudy day the light was soft and and allowed the details of the feathers to come out. And then we have that adorable little fluff ball of a chick. Can’t argue with that. And I like the family moment as the ever watchful parents guard over their little one. The bend of the neck really adds something. I love the collection of plants in the front and then the layers of out of focus colors in the background. The purple adds a little zip to the composition.

And voila, put all the different elements together and we get a very pleasing image.

Canada Geese are native to the arctic and temperate regions of North America, though they will sometime migrate to parts of northern Europe. They have also been introduced to the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Argentina, Chile, and the Falkland Islands. As to WHY they would do that, I have no idea.

Normally these geese will fly south for the winter; as a child I remember seeing the large V-shaped formation of birds flying overhead — a clear sign that winter could not be far away.

But with the changing climate, the nature of human settlements, and farming patterns, many Canada Geese are beginning to shorten the distance they fly or, increasingly, becoming permanent residents of parks, golf courses, and suburban sub-developments. Changes in farming practices leave more waste grain available for the geese making it easier to stay put. Also the proliferation of lawns and grassy fields are ideal habitats for Canada Geese — grass is part of their diet so their buffet has grown in size, and the manicured lawns are attractive because they provide a wide, unobstructed view of potential predators. As a result these birds are especially abundant in parks, airports, golf courses and other areas with expansive lawns.

Canada geese were not always so numerous. In the early 1900s they were almost pushed to extinction due to over-hunting and loss of habitat. Tougher hunting policies and other programs helped stem the tide, and the bird’s ability to adapt to the nature of human settlements has allowed the Canada Goose to not only thrive but in some areas, become a pest. For example, just fifty geese can produce about 2.5 tons of poop in a year. A flock of Canada Geese can turn your local park into a very icky slip and slide. We now have about six million Canada Geese in the US. Dat’s alotta poop.

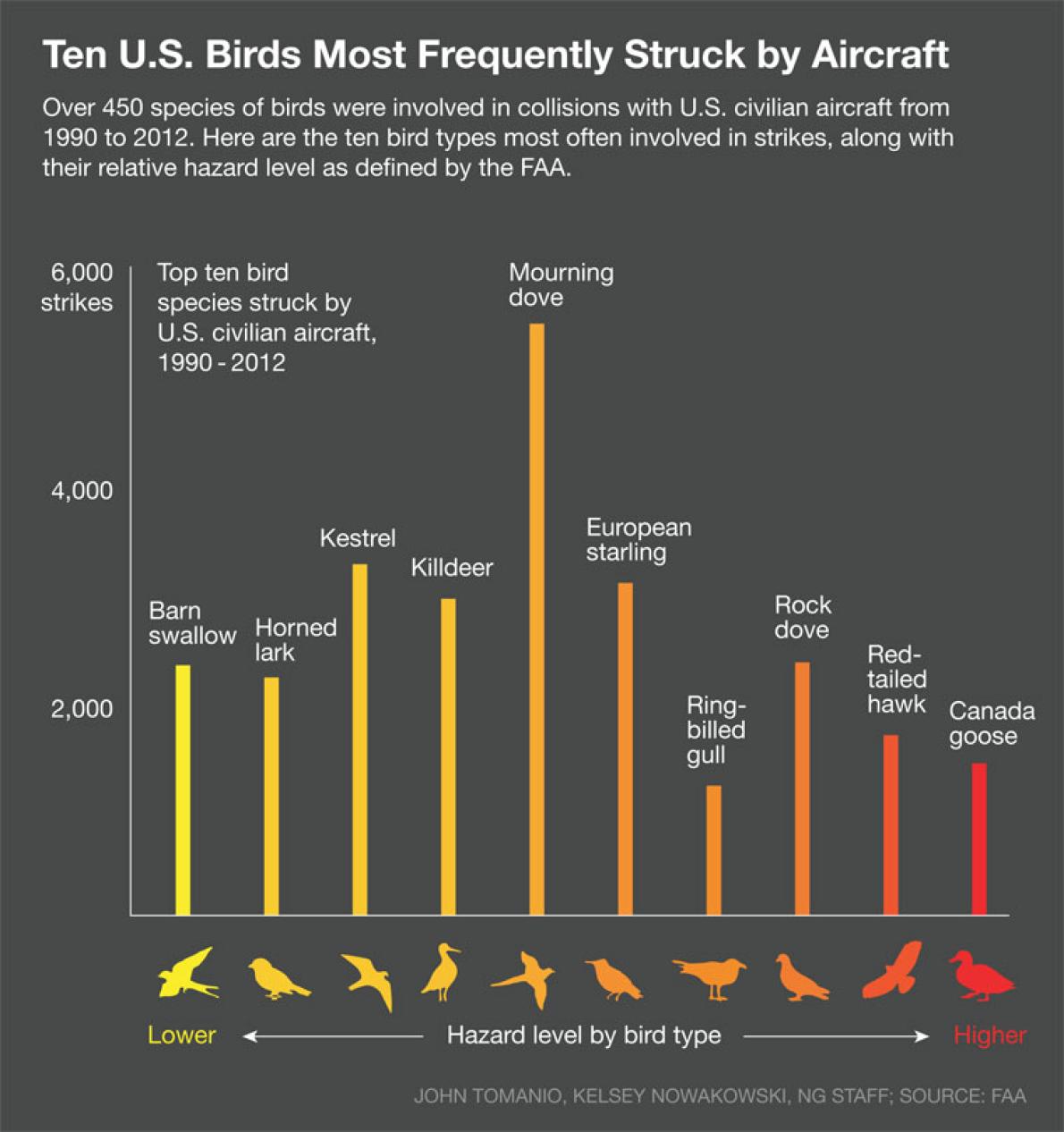

Because of the large size of Canada Geese, they are a major concern at airports because they can cause fatal crashes when they strike an aircraft’s engine. Remember the “Miracle on the Hudson” when a US Airways plane that took off from Laguardia Airport in New York in 2009 and had to ditch in the Hudson River? As the plane took off it collided with a flock of Canada Geese. Luckily Captain Sullenberger (Sulley) managed to execute a perfect “water landing.”

So, I am still rather ambivalent about the world’s largest goose, though I do have to admire its resilience — back from the precipice to pest in just a hundred years. Uh, well done!?

Until next month…..

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/11, 1/200 s, 1.4x TC, ISO 800, EV +0.5

31

July 2017 – Shot of the Month

The tallest mountain in Washington state, Mt. Rainier, is famous for its glorious summer wildflower blooms. In 2016, with our first summer in the state approaching, we decided that we should make the pilgrimage to catch Mother Nature’s wonderful show. Such a trip however would push me out of my comfort zone on several fronts — first, I am not a fan of mountain hiking (at least not with many pounds of camera gear); and second, I rarely shoot landscape photography so I tend to struggle to “find the the shot.”

So we cobbled together two long weekends to toil up and down mountain trails in search of colorful flora. I lumbered under the weight of my gear and generally grumbled most of the way. Lots of work for little reward.

However, on the next-to-last day, we found a mother marmot with two youngins right by a popular trail. These Hoary Marmots (HMs) were very comfortable with humans and we could readily watch them as they came and went from their burrow and explored the stream and hills nearby. As an “Easterner,” I was quite excited by my first marmot encounter. I ran back to the car to get my big lens to allow me to photograph these guys properly.

Photographing critters, “ahhhh…back in my element.” I love this shot in that it gives a nice view of the marmot and offers a small hint of the bouquet of flowers beginning to cover the meadows and surrounding hills.

I have since learned that marmots were actually not that exotic to me — in fact, I had grown up around marmots my whole life while in Pennsylvania. How so? Turns out that what we call groundhogs (aka woodchucks) in the east are also a type of marmot. There are 15 marmot species, classified as large ground squirrels by scientists, and they are spread far and wide across the Northern Hemisphere in places that include Canada, the US, Europe, and parts of Asia. Most of these species prefer Alpine habits but some can be found at lower elevations.

The hoary marmot, as photographed here, can be found in the mountains of much of Alaska, western Canada, and the extreme northwest of the United States. The HM is a social creature that can live in colonies of up to 36 individuals — a colony can be spread across 35 acres and includes a dominant male. This group living is quite different than that of my childhood woodchucks who live solitary lives.

These cute rodents are vegetarian and live on leaves, grasses, and sedges, and these rascals will devour the gorgeous wildflowers before your eyes with no shame.

Though, in their defense, while the sign says “Stay off the flowers,” it actually says nothing about not eating them.

Until next month….m

Nikon D4s, Nikon 600 mm, f/8, 1/640 s, ISO 800, +0.5 EV

30

Shot of the Month – June 2017

So no, I don’t have a studio — this image was shot in the wilds of nature at the Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge. These lovely Snowy Egrets (SEs) had gathered en masse with a large collection of other herons and assorted egrets during a feeding frenzy along a dark mangrove channel. To properly expose for the pure white bird, in bright sunlight, I had to significantly underexpose the shot — which produces this dramatic “studio” look.

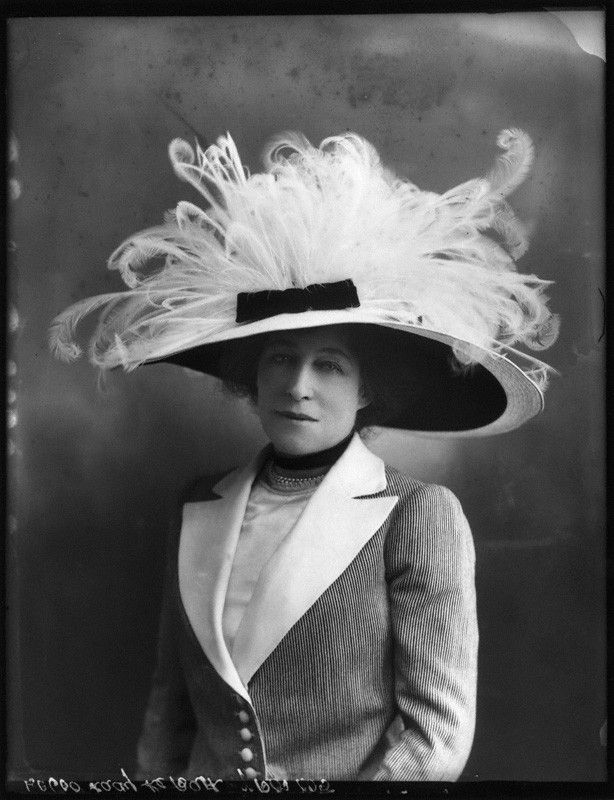

This image was shot in December when the SEs are beginning to morph into their exquisite mating plumage — during this period they develop long wispy feathers on their backs, necks, and heads. As the season progresses the coloration on their faces will transition from yellow to reddish. And those bright yellow feet will take on a richer orange-yellow hue.

In the late 19th century Snow Egrets were almost wiped out as they were decimated by hunters collecting the breeding plumes for use in women’s hats. In 1886 these plumes fetched $32/ounce which was twice the value of gold at that time. During the “Plume Boom” hundreds of millions of birds were killed — for example from 1901 to 1910 over 14 million tons of feathers were shipped to the United Kingdom with a value of 20 million pounds. Wow, that’s a lot of feathers. (source)

And a lot of dead birds.

Fortunately, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 curtailed much of this slaughter and today the population of Snowy Egrets and other herons has improved quite a bit.

Snowy Egrets eat mainly fish, frogs, worms, mice, crustaceans, and insects. They typically stalk prey in shallow water, often running or shuffling those brightly colored feet, flushing prey into view. They will also sometimes catch prey while “dip-fishing” as they fly with their feet just over the water.

Snowy Egrets are permanent residents in most of South and Central America. In the US they can be permanent residents along the Atlantic coast north to Virginia Beach, Virginia, along the Gulf Coast, and along the Pacific lowlands from central California southward. During the breeding season, snow egrets can be found as far north as Rhode Island.

With its lovely, delicate, and refined looks one could easily imagine a Snowy Egret as a runway model. Rather ironic given that high fashion almost wiped out this elegant bird.

Silly, terrifying humans…

Until next month.

Nikon D4s, Nikon 200-400 mm (@ 200mm), f/4, 1/4000, ISO 400, -1.5 EV

31

Shot of the Month – May 2017

This month we visit with a ram that fully embraces his name – the Bighorn Sheep (BHS). We found this big fella in Yellowstone National Park and our guide mentioned that this was one the largest set of horns he had seen in 30 years of visiting the park.

This month we visit with a ram that fully embraces his name – the Bighorn Sheep (BHS). We found this big fella in Yellowstone National Park and our guide mentioned that this was one the largest set of horns he had seen in 30 years of visiting the park.

As I discussed in a previous post, “Bighorn Sheep” is a rather chauvinistic name for the species as the females also have horns, though they are not nearly as big, nor curved. The lads get all the attention, a-gain.

These rams definitely know that they are impressive — this one walked by me with his shoulders back, chest out and his head raised, as if saying, “Yes, soak it in, I am magnificent.”

Those horns can weigh 30 pounds, equal to the weight of all the other bones in the ram’s body. A ram can weigh 174 to 319 pounds so those horns can make up about 10% of their total body weight.

Mature males spend most of the year as part of a bachelor flock. Ahhh, those were the days…

The rams join the female groups in November when the mating season begins. The BHS rams are most famous for their epic head-clashing battles to win the right to mate with the females.

These fellows will smash their heads together as they hurl themselves at each other at 20 mph — generating about 800 pounds of force – sixty times more force than needed to kill a human. The rams can survive these violent collisions because their skulls have two layers of bones above the brain that act as shock absorbers. The sound of these collisions can be heard from a mile away.

These battles can last for 24 hours until one sheep decides that he has had enough and simply walks away. Wait, that’s it??!! I expected a denouement with a bit more operatic panache given the fury and scale of the spectacle.

Oh well. The clash of the Mountain Titans ends with a quiet, “I’m out.” I suppose that there is a certain civility in that.

You can catch the mind-numbing show here. (I wasn’t able to embed the video)

The prelude to the fight can be seen below (very nice footage).

In case you were wondering, the title of this post is a nod to Bam Bam Rubble…an adorable character from my youth who seems to capture the simple essence of a bighorn ram’s approach to life…

Until next month…m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm f/4, 1/800 sec, ISO 800, +0.5 EV

30

Shot of the Month – April 2017

Another shot for the “Awwwl” Collection. For those of you not keeping score at home, this collection includes huddling hyraxes, a burrowing owl, loon chicks with mom, and a pika. This image is a favorite among moms everywhere and is one of my most popular cards. I photographed this adorable baby elephant in Botswana.

Female elephants live their entire lives as part of a tightly-knit family group. Life in the herd revolves around breeding and the raising of calves. A new calf is typically the center of attention for all herd members. The little one photographed above must be pretty new — it is so small that it could easily walk under the elephant behind it.

Females are ready to breed at the age of thirteen and will give birth after a 22-month pregnancy. At birth, all of the other elephants will gather around the newborn to touch and caress it with their trunks. In the video below you can see a herd’s reaction to a newborn.

Soon after birth, the mother will select several full-time baby sitters or “allomothers” from her group. These allomothers will help in all aspects of raising the calf. The more allomothers a baby has the more free time the mother has to feed herself and produce nutritious milk, increasing the chances of survival for the calf. The allomothers also benefit by gaining experience on how to raise a calf which makes them better mothers when they are finally ready to breed.

Here you can see a whole herd come together to help a baby elephant that is stuck in a water hole:

Given all that love and protection, baby elephants seem free to enjoy life. I have watched them play in rivers and they are just like human children at the beach. They run and chase each other. They splash one another and the teenagers knock the smaller ones over – all in good fun. Check out this little guy (the fun starts around 0:35 seconds):

There is an African proverb that says “It takes a village to raise a child.” Gee, I wonder where the inspiration for that may have come from?

Until next month…

31

Shot of the Month – March 2017

Here we see an Osprey doing what it does best — catching a fish. This was one of the first images I ever captured of an osprey in action. I have to confess however that this is not a completely “wild” setting. Let me explain.

A couple of years ago while living in Vermont I heard about ospreys that regularly visited a fish hatchery that was about an hour from where I lived. The hatchery had an assortment of holding tanks that held fish from uber small to quite big. The biggest fish, rainbow trout, in this case, were held in an outdoor pond. For an osprey, this was like shooting the proverbial fish in a barrel.

Initially, the osprey parents would stop by to catch a couple of fish each day to feed themselves and the kids. When the chicks were old enough to fly the parents would bring them to this pond to practice fishing. I heard about the spectacle and spent a couple of weekends sitting by the pond to see what I could catch. It was interesting watching the parents circling above as they called out to their offspring, seeming to implore them to give it a go. It was easy to distinguish the parents from the newbies — the parents would circle briefly and dive in with great confidence and efficiency. The kids, uh, not so much. They would start a dive and then abort. Come in for another try and pull up at the last second as they got close to the water. Eventually, after numerous false starts, they would dive in, occasionally catching a meal.

As for me, I had a grand ole time. I had a front-row seat and could see up close and personal how an osprey earned a living.

Ospreys are true piscivores — fish make up about 99% of their diet. Given their love of fish, osprey nests are usually found within 12 miles of a body of water. They typically fly about 30 to 100 feet above the water surface and use their exceptional eyesight to spot a meal. Osprey tend to prefer shallow bodies of water since it can only plunge about three feet under the water’s surface with its feet-first dives. These hawks are pretty good at what they do and usually catch a fish in 1 out of 4 tries. It takes an experienced adult about 12 minutes of hunting before making a catch.

The osprey’s feet are highly adapted to facilitate holding on to its slippery catch. Osprey can shift one outer toe to the back if needed to better grasp a fish. No other birds of prey can do that. Their feet also have barbed pads on the soles and the talons have backward-facing scales — all adaptions to help maintain a firm grip. To facilitate an efficient flight back to the nest or the preferred dining locale, an osprey will orient the fish headfirst to minimize wind resistance!

As they say, you can teach a man to fish, but he still won’t be as good as an osprey. Or something like that.

Until next month…

Here is a great video showing how osprey hunt:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm, f/8, 1/2000 s, ISO 800, -0.5 EV

28

Shot of the Month – February 2017

This month we visit with the natural world’s “Unbreakable” star – the coyote. I photographed this fine-looking fellow in Yellowstone NP. For the uninitiated, the film “Unbreakable” is an American film about a man who learns that he has supernatural powers and basically, he can’t be killed. The Coyote, at least as a species, seems to have similar powers. (I recommend the film, if you haven’t seen it)

In the last two hundred years we have done a wonderful job of wiping out many of the continent’s top mammals. Fifty million bison were reduced to about twelve thousand. The grey wolf used to inhabit the entire United States but is now largely extinct from most of the country. The North American cougar was extirpated in the eastern half of the country by the beginning of the 20th century.

And we have been working overtime to kill off the coyote. We kill a coyote every minute in the United States. I’ll repeat that morsel, in case you blinked.

We kill a coyote every minute in the United States. In other words, we kill about 500,000 coyotes each year.

Coyote Killing Contest (Source)

We are very determined to wipe this animal out. In the 1920s the US government created the Eradication Methods Laboratory whose sole job was to kill predators that we didn’t like. Congress passed a bill in 1931 allocating $10 million to the lab to launch a poison campaign. From 1947 to 1965 the agency killed about 7 million coyotes using blanket poisoning, sometimes putting out up to 4 million poison baits at a time. Since the 1970s this job was handed over to the Wildlife Services Agency, which is part of the Department of Interior. Since 2000 the agency has killed 2 million mammals (coyotes, wolves, and cougars) and 15 million birds. More recently the government uses airplanes to shoot about 80,000 coyotes per year on behalf of the livestock industry. Many states have a bounty on coyotes and you can pretty much kill coyotes at will in many places. In some states, they have contests to see who can kill the most coyotes in one day.

Normally, this is the part where I tell you how dire the situation is for the coyote. How they are highly endangered and near extinction. Not this time, my friends. As I mentioned, the coyote is unbreakable.

In fact, the coyote is THRIVING. Never been better, thanks for asking!

How is that possible??!!

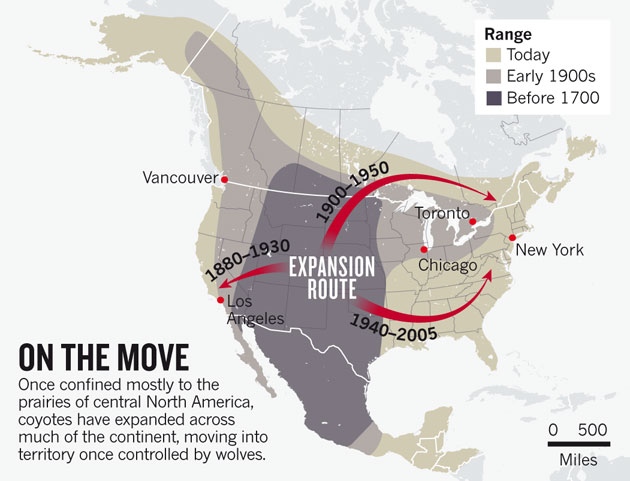

The coyote’s superpower is adaptability. They are masters of exploiting the changes in the environment caused by humans. When the settlers arrived coyotes only lived on the western plains but once we killed off the wolves everywhere else the coyotes began to migrate into new territories and they now occupy most of the continent.

Coyotes historically were smaller than wolves and couldn’t compete with them. In the 1800’s the wolf population was at a low density due to human persecution and wolves had a difficult time finding a mate. As coyotes migrated east the wolves took the next best option and mated with their smaller “cousin”. As a result, the northeastern coyote-wolf hybrids were bigger, stronger, and able to kill larger game. This allowed coyotes in the east to be able to kill deer, something their smaller relatives in the west are unable to do.

Coyotes have also moved into urban centers and seem to love life in New York City, Washington D.C., Chicago, and Los Angeles, to name a few of their favorite haunts. Turns out that cities are pretty safe because people are not shooting, trapping, or poisoning them there. The coyotes adapted their diet to eat squirrels, household pets and discarded fast food. In rural America coyotes live for about 2 to 3 years while in the city a coyote can live for 12 to 13 years!

Under normal conditions, coyotes have 5-6 pups in a litter. However, when the coyotes feel persecuted they increase their litter size to 12 to 16 pups. You can kill off 70% of coyotes one year, but by the next summer, their numbers will have recovered. They use howls and yipping to create a kind of census of the coyote population. If their howls are not answered by other packs, it triggers an autogenic response that produces larger litters. (Source)

Coyotes also developed a fission-fissure adaption to help them survive. If life is going well, coyotes will live and hunt in packs. However, if they are persecuted, say by wolves or humans, then coyotes will abandon pack life and scatter across the landscape in singles or pairs. For example, the poison campaign of the 1970s really helped scatter coyotes across the country.

There you have it, another sad tale that makes me embarrassed and ashamed to be a human. But congrats to the coyote for stickin’ it to the man. I’m rooting for ya!

Check out Project Coyote to learn how you can get involved to stop the slaughter of coyotes and MANY other animals.

For more outrage, click here:

National Geographic article on the Wildlife Services Agency

Washington Post article on the Wildlife Services Agency

I got much of my information for this post from these great articles. Highly recommended:

How the Most Hated Animal in America Outwitted Us All (National Geographic article)

Rise of the coyote: The new top dog (Nature Journal article)

Until next month…..

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm f/4 lens @ f/8, 1/2000 s, ISO 400, EV +0.667

31

Shot of the Month – January 2017

As you may recall from an earlier post, I am a BIG fan of owls so it is an exciting day when I get to add a new owl species to my portfolio. Let me introduce the Short-eared Owl (SEO), as captured here in this lovely winter scene that I found about an hour north of Seattle. Upon moving to Washington State I learned that Short-eared Owls (SEOs) winter over in my new state to escape the cold of northern Canada. Accordingly, I have been spending many a chilly weekend out looking for these aerial acrobats.

Owls can be very hard to photograph as they are usually most active at night. SEOs are one of the easier owls to view, relatively speaking, in that they often hunt during the day. Bless them.

The Short-eared Owl prefers open terrain and can be found in prairies, coastal grasslands, meadows, savannas, tundra, marshes, and other low-vegetation habitats.

These owls specialize in hunting voles and other rodents. The owl usually flies just a few feet off the ground as it scans for a meal — its flight can be highly erratic

and undulating. As it listens and looks for prey it may suddenly bank to one side or another, or slam on its air brakes to drop to the ground feet first to grab its victim. Sometimes it will hover over a spot as it waits for an opportunity to pounce.

Imagine a large moth flying over a field and you will have a sense of its herky-jerky flying style. As a photographer, I can tell you that trying to capture an image of an SEO in flight is one of the most difficult types of photography I have tried to do. I will be tracking it, tracking it, just about ready to release the shutter, and then, poof, the bird vanishes from the viewfinder. This happens A LOT.

On a typical day, I will arrive at sunrise and take up a position in the field. And then I wait. As the sun rises, and the voles and mice become more active, the SEOs suddenly appear from the ether. I have seen as many as seven SEOs working a large field at the same time. The owls crisscross their way over the terrain in sortie after sortie as they look for prey. It is an amazing scene to behold though it must be a rather terrifying experience if you are a vole.

On a typical day, I will arrive at sunrise and take up a position in the field. And then I wait. As the sun rises, and the voles and mice become more active, the SEOs suddenly appear from the ether. I have seen as many as seven SEOs working a large field at the same time. The owls crisscross their way over the terrain in sortie after sortie as they look for prey. It is an amazing scene to behold though it must be a rather terrifying experience if you are a vole.

The airspace above these fields will soon fall quiet as the owls begin to migrate back north for mating season which starts in March. I imagine that spring can’t come soon enough for the voles — a few months respite from the constant onslaught from those malevolent, murderous moths.

Until next month…

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm f/4, 1/1600 s, ISO 1600, +0.5 EV