30

Shot of the Month – June 2019

This month a photo of a tulip that demonstrates the power of isolating your subject to help create a compelling image. In this shot there is no doubt about what this photo is about — our eyes can’t help but be drawn to that lone red tulip in the center of the frame. In this image I used several techniques to isolate the subject:

Choice of depth of field

In this shot I used a very shallow depth of field (aperture of f/5.6) to ensure that almost all of the other flowers in this field were out of focus. Our eyes are naturally drawn to the part of the image that is in focus. For comparison look at the same image taken with a very wide depth of field (aperture of f/22). In this version  the field of flowers is more in focus and, at least for me, more distracting. I find that my eye jumps around more from one part of the photo to the next and weakens the visual impact. Click on the image to see it larger. Here is a primer on understanding depth of field.

the field of flowers is more in focus and, at least for me, more distracting. I find that my eye jumps around more from one part of the photo to the next and weakens the visual impact. Click on the image to see it larger. Here is a primer on understanding depth of field.

Point of View (POV)

To get this image I shot while crouched on my knees to get a low angle — this allowed me to shoot up and through the red flowers in the foreground and create depth in the image. This POV also allowed the red tulip to appear higher into the field of purple in the background and helped create more separation and space between the subject (red) and the foreground (red). Don’t be afraid to move around and explore the scene to make sure you are including the elements you want in the shot, and perhaps even more importantly, explore how your POV can help remove elements that weaken your image. Try higher. Then lower. Move to the right. To the left….shake it all about….

Contrasting Color

I was immediately drawn to this scene by how the red tulip popped visually against that purple background. The lovely green stem of the subject also adds more contrast and leads the eye to the subject.

Centered Subject

While it is often not recommended to center your subject it can sometimes be a useful technique under the right circumstances (See my post here on this topic). I usually try multiple compositions with the subject to the left, right and centered to help find what works best for the scene. I also often shoot in both landscape and portrait orientation to see which leads to a stronger composition. Given the vertical nature of the flowers portrait orientation worked best.

Wow, so much to consider to just get a pretty picture of a flower! These are in fact just a few of the ways that one can isolate the subject of an image. What are the others? Hmmn, that sounds like fodder for a future post….I just need to get outside and get the shot….stay tuned.

Until next month…m

31

Shot of the Month – May 2019

This month we visit with the glorious Selasphorus rufus, aka the Rufous Hummingbird. For those of you who are a bit rusty on your color palette (I was):

Rufous: reddish brown in color.

So while the name is not terribly creative it is accurate. The male Rufous is adorned in reddish brown on the crown, tail and sides. His back can be rufous, green or a bit of both. But the pièce de résistance for the male is that flame-orange gorget. Gor-what? It is a term that refers to the piece of armor that knights wore to protect their throats. It now refers to the patch of color that can be found on a bird or animal. The intense glint of the gorget is the result of iridescence, rather than colored pigments. The bird’s throat feathers contain minutely thin, film-like layers of “platelets,” set like tiles in a mosaic against a darker background. Light waves reflect and refract off the mosaic, creating color in the manner of sun glinting off oily film on water. The color and intensity of the gorget changes depending on your angle of view. (Source) The female Rufous is not nearly as flashy — she typically is greenish above with rusty-washed flanks, rusty patches on her green tail with a spot of orange on her throat. (Source)

In researching the Rufous I was surprised to see how often the word “fiesty” came up. One article said that the bird was “well known to be incredibly feisty and pugnacious.” As far as hummingbirds go the Rufous is considered to be on the small side, usually between 2.8 to 3.5 inches and weighing about 3.5 grams. For comparison a US penny weighs about 2.5 grams! Apparently no one told the Rufous — they are commonly considered the most aggressive of the hummingbird species! As one literary-minded observer noted:

“The male Rufous, glowing like a new copper penny, often defends a patch of flowers in a mountain meadow, vigorously chasing away all intruders (including larger birds).” (Source)

Ever have a Rufous at your backyard hummingbird feeder? Yikes — I can tell you from personal experience that they defend those feeders with equal zeal. They drive off other hummingbirds, bees, wasps, birds and other insects without respite. I had one hover 2 inches from my face trying to scare me off. We eventually set up more feeders around the house to try and give the other hummingbirds a chance at some food.

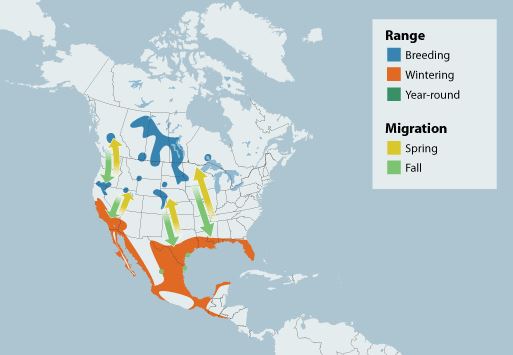

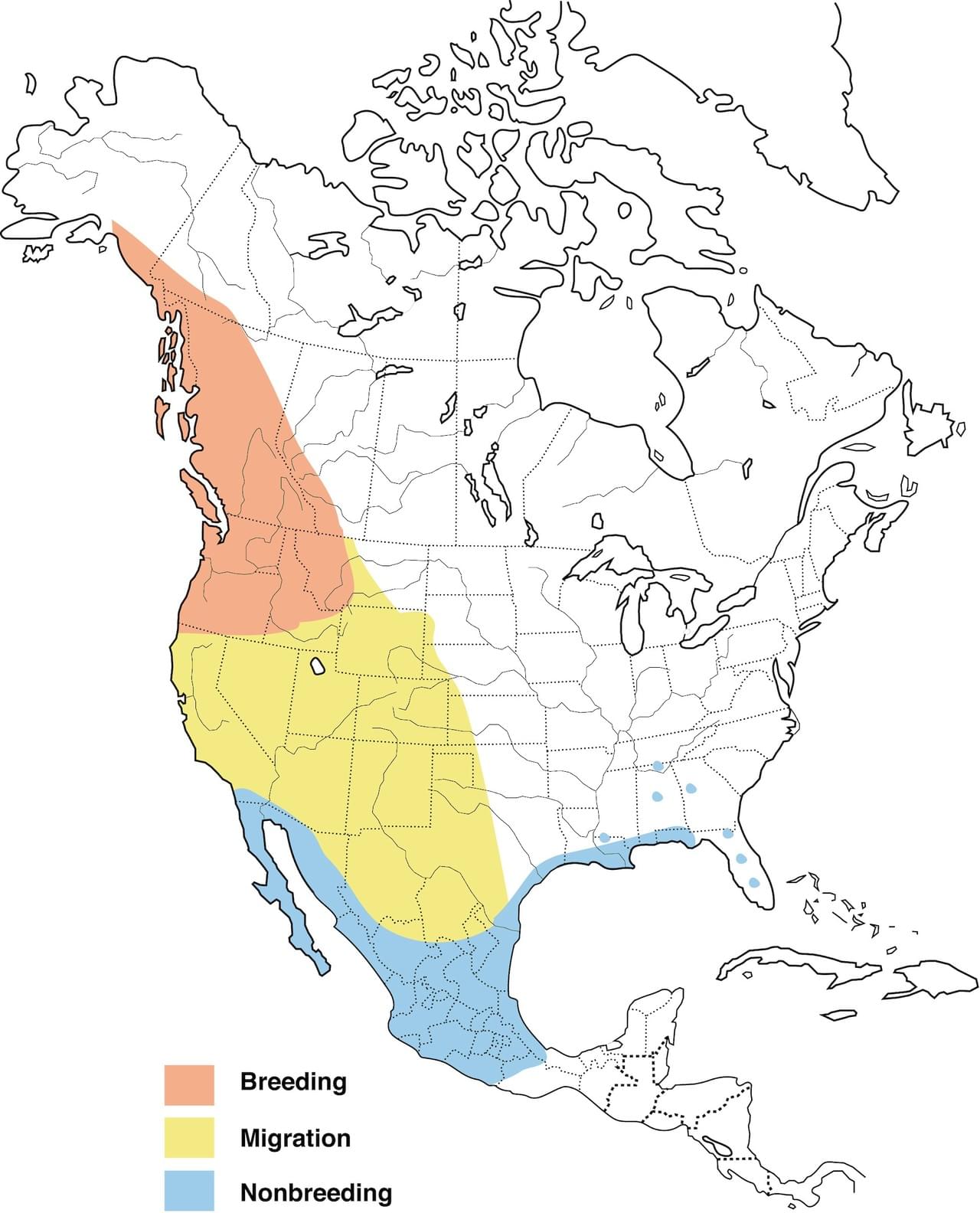

Rufous Hummingbird Range (Source)

Like other hummingbirds the mainstay of their diet is protein and sugar. They get their sugar by feeding on the nectar from colorful, tubular flowers which they access with their long extendable tongues. Preferred flowers include columbine, scarlet gilla, penstemon, indian paintbrush, mints, lilies, fireweeds, larkspurs, currants, and heaths. The flying pennies get their protein and fat by catching insects like gnats, midges and flies in the air. They will take aphids off of plants also. Given their frenetic lifestyle they consume three times their body weight in food each day. The Rufous has a fantastic memory that helps it find flowers and feeders along its long migration route from previous years. (Source)

Speaking of which, the Rufous hummingbird has the longest migration of any hummingbird — they can fly up to more than 2,000 miles in one direction from the northwest United States down to Mexico and the Gulf Coast where they winter. While the Rufous hummingbird is found predominantly in the western US this far ranging bird has been spotted in every state except Hawaii. These guys get around!!

I can’t help but admire this little bird — the Rufous is a real beauty to behold, is a tremendous athlete, has a sharp mind, and has the fighting spirit of a heavy weight boxer – all rolled up into a thimble-size body!

Until next month…..michael

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/500 sec, ISO 400, -0.333 EV

30

Shot of the Month – April 2019

This month we visit with the most powerful cat in the Western Hemisphere — the Jaguar. This heavyweight of the feline world is the third largest in the world, coming in just behind the Lion and then the Tiger. The jaguar is the only member of the “Big Cats” that is found in the Americas. I photographed this jaguar in the Pantanal, in Brazil.

Looking like a heavyset leopard these cats are built for life in the tropical rain forest where they are found — they have muscular limbs and large paws which allow them to climb trees and swim rivers with ease. Unlike most felines, these cats absolutely love the water and rarely stray too far from the river. That being said, they are adaptable and can be found in other habitats including grasslands and deserts.

The jaguar is a stalk-and-ambush hunter unlike lion and cheetah which chase their prey. These cats walk slowly, and silently through the jungle in search of a meal. They also walk along the river’s edge, or even in the water as seen in my image above. We watched this impressive male, known locally as Mick Jaguar (Groan, I know. It doesn’t seem as corny when you are there seeing this incredible cat….) hunt along the river for several hours. Even though Mick is past his prime now, perhaps 11 years old, he is still the top cat in this part of the river. You can see that his one eye is injured but we were told that he can still see with it.

Medium-sized mammals make up the majority of Mick’s diet and can include deer, capybara, Peccaries, and Tapirs. When hunting in the water prey may include turtles, fish, and caiman (a relative of the crocodile and alligator). In total Mick and his brethren can take over 85 species depending on what they can find. One of the few jaguars that lived in the US was known to even kill and eat American black bears. (source)

Like most big cats Mick kills large prey with a deep throat bite that suffocates the animal. Jaguars have the most powerful bite of any cat and sometimes kill their prey by biting through the animal’s skull! When hunting large caiman the jaguar will sometimes jump on the back of the reptile and bite through the base of the skull and sever the cervical vertebrae which instantly paralyzes the animal.

Blah, blah, blah. So many words. Watch this unbelievable video of Mick himself on a hunt from several years ago– this video will show you everything you need to know about the hunting style of the jaguar, their fearless nature, and their lethal hunting techniques.

Any questions? WOW!

Until next month…..m

Want more?….

Check out my other post on the Jaguar.

And a few more videos:

A different angle of the same hunt as shown on National Geographic

And a short piece as shown on Nature about the Jaguar

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm f/4, 1/800 sec, ISO 250, +0.5 EV

28

Shot of the Month – February 2019

One of the highlights of our 2018 trip to Kruger NP (South Africa) was the magical three hours we spent with a pack of 24(ish) wild dogs. We counted 12 puppies(!) and about 12 adults in one of the largest packs I have ever seen. The pack spent most of the morning sprawled out on both sides of the road. The puppies were on one side and the adults on the other. About every 30 minutes or so, the alpha female would get up and walk over to make sure that the puppies were doing fine. After a few visits by the female, the alpha male got up (trying to be helpful?) and went over to check on the youngins. Well, Dad got too close and woke up the pile of puppies. Chaos ensued with all sorts of yelping and clamoring and assorted mayhem. The alpha female, very annoyed, had to get up and go over and severely reprimand the whole crew. She “bit” a couple of them (in a lovingly, mother kind of way, ouch!), snapped at a few others, and eventually got them to lie back down. Future monitoring visits were done by Mom…..

In case you were wondering, wild dogs are not feral domestic dogs that live in Africa. Wild dogs, also known as the

painted hunting dog,

painted wolf,

African hunting dog,

Cape hunting dog, or

African painted dog

have never been domesticated.

The scientific name for these canids is Lycaon pictus which means “painted wolf” in Latin. The painted hunting dog is part of the Canidae family which includes jackals, foxes, coyotes, wolves, dingoes, and domestic dogs. People often confuse wild dogs with hyenas but hyenas are bigger and more powerful and different enough that they belong in their own taxonomic family, Hyaenidae.

The theme song for a pack of wild dogs would be “We Are Family” (If animals had theme songs, that is. Which for the record, I heartily endorse. I like what the sharks have done with theirs…). The social structure of the pack is much like that of wolves but much gentler. There is a tenderness to wild dog life, unlike anything I have ever seen. Like other pack animals, there is a strict hierarchy with the pack led by an alpha breeding pair. All other adults are subordinate to this couple. Only the alpha female will breed and can produce 10 to 12 puppies per litter — the most of any canid. However, the entire pack raises and cares for the puppies. While the puppies are small the pack will go off to hunt while some adults stay behind to protect the puppies in the den. After a successful hunt, the adults will return and regurgitate food to feed both the puppies AND the “babysitters.” When the pups are old enough to travel they will be escorted to a kill site and they are always the first to feed before any of the adults, even those that participated in the hunt. If an adult becomes ill, injured or elderly, and is unable to hunt, the other dogs will share food and take care of the ailing member. It is reported that the alpha female of a pack in Botswana lost one of her forelegs during a hunt. Normally, this would be a death sentence for a predator. Not for a wild dog — she remained the alpha female for a few more years continuing to breed and raise pups while being taken care of by the pack. (source)

Wild dogs are so team-oriented that they vote on whether to go on a hunt. Yes, really.

So how in the heck does that work?? Well, if a dog wants the team to get going to look for a meal s/he can sneeze to rally the pack to get going. However, voting is weighted depending on rank. If an alpha dog sneezes then only about three other “yea” votes are needed to launch a hunt. If a lower-ranked dog kicked off the voting, a hunt would not start unless about ten other sneezes were counted. (Source)

Wow, that is some bad-ass-African-plains-wild-dog democracy right there — definitely nothing to sneeze at. (the crowd moans…)

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/500 sec, ISO 1000, EV +1.0

31

Shot of the Month – December 2018

In North America, a snowbird is a slang term used to describe someone (often a retiree) who migrates each winter from his northerly, typically very cold home state to spend the winter in a warmer state like Florida or Arizona. While living in Vermont – a very northerly, and VERY coldly state in the winter, we adopted some sunbird-esque habits and spent Christmas visiting family in Florida two years in a row. These trips allowed me the opportunity to photograph a range of wildlife in Ding Darling Nature Reserve. During one outing I captured a photo of a big bird — not THE Big Bird, but his cousin, the American White Pelican (AWP).

How big? Well, the AWP has a nine-foot wingspan, which you can see in all its glory in the image above. A male can stand almost 4 feet tall and can weigh thirty pounds! That massive bill can add almost another 2 feet to the length of this bird. These Goliaths are among the heaviest flying birds in the world. Despite their size, those massive wings allow the pelican to excel at soaring and they can be seen traveling long distances in V-formation.

These birds breed and spend the warmer months in the heart of northern North America and spend the colder months in warmer locales as you can see in this range map.

The AWP is very gregarious and they often travel and forage in large flocks. Some pelican species plunge-dive to catch their prey — not these guys. The AWP feeds from the water’s surface, dipping their beaks into the water to catch fish and other prey. The birds will often work together to corral fish to one another. Sometimes a group of birds will dip their bills into the water together and flap their wings to drive fish toward the shore where the water is shallow. This then allows for a very efficient, collective feast.

The American White Pelican can eat up to four pounds of food a day with fish (carp, Tuie chub, shiners, perch, rainbow trout, jackfish, catfish, etc.) being the preferred meal. The AWP is not above theft, known as kleptoparasitism in the animal world, to catch a meal and they can often be seen stealing fish from other pelicans, gulls, and cormorants.

Once a fish, or two, has been caught the pelican will raise its bill to drain the water and swallow the prey.

Gregarious, larger than life, a healthy appetite, and seasonal migrations — it sounds like this pelican might be a subspecies of snowbird. If you get my drift….. 😉

Until next month…

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, 1.4X TC (effective 850 mm), 1/2500 sec, ISO 400, -1 EV

30

Shot of the Month – November 2018

It looks like somebody is having a bit of a tantrum. Check out those pursed lips and the dust caused by the stamping of the foot. The thought bubble may say something like “Everybody off!” I photographed this white rhino, and his bird friends, in Kruger NP, South Africa.

Despite the humorous nature of this photo, the reality is that any image of a rhino is bittersweet. We are obliterating these beasts and they are hurtling toward extinction. Any photo taken now could simply be capturing the last of a kind.

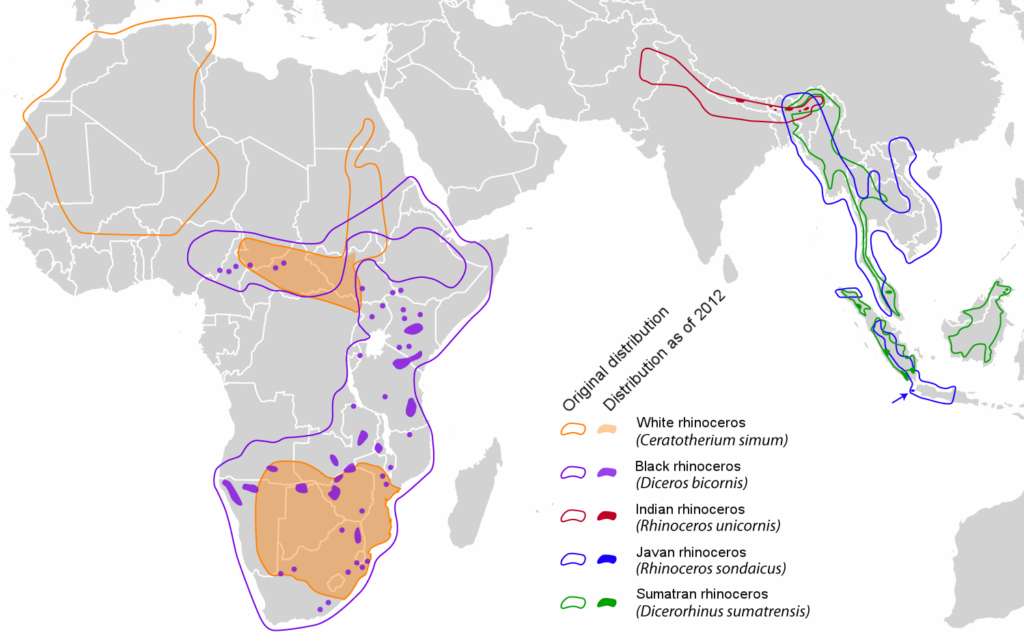

There are five remaining species of rhino. Look closely at this map (click on it to see it larger) and take note of the former range of these animals compared to the reality today. Can you find the dot that represents the last enclave for the Javan rhino?

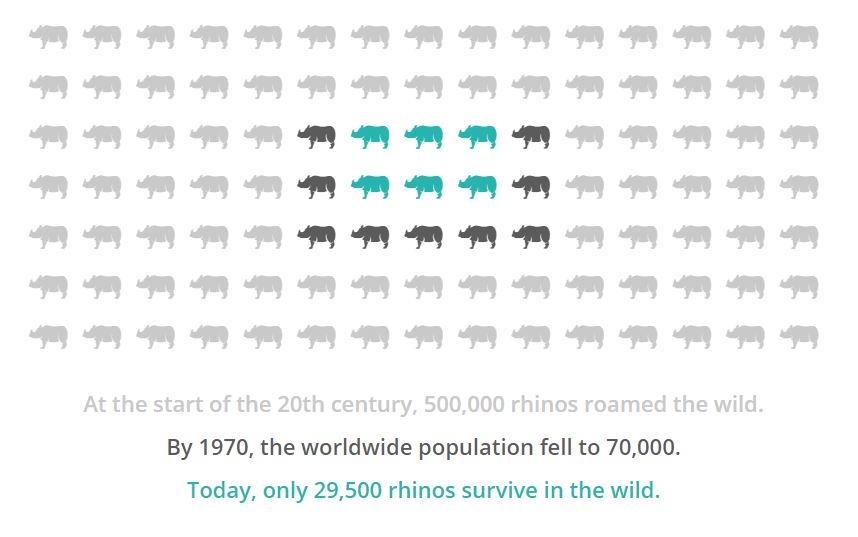

In the last hundred years we have decimated the rhino population (Source):

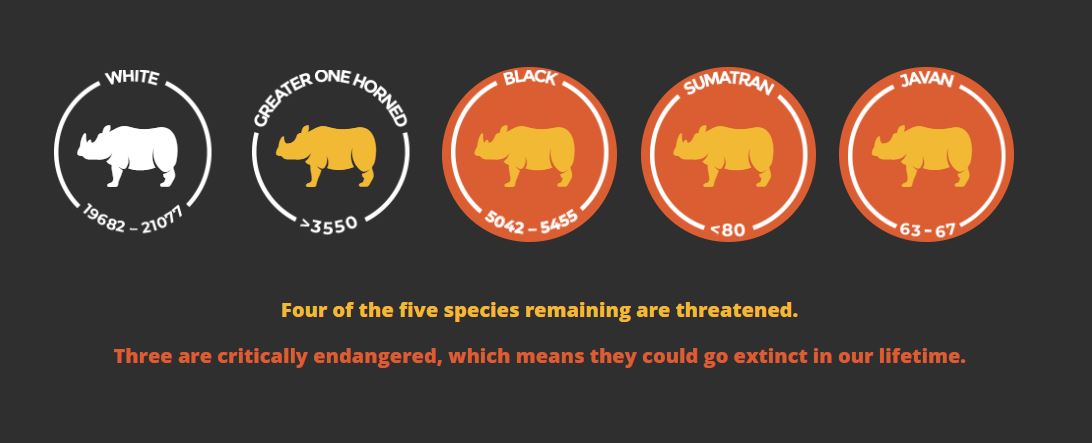

Africa is home to 2 species (Black and White) and Asia is home to 3 (Indian (also known as the Greater One-horned Rhino), Javan, and Sumatran). How are they doing? Not great (Source):

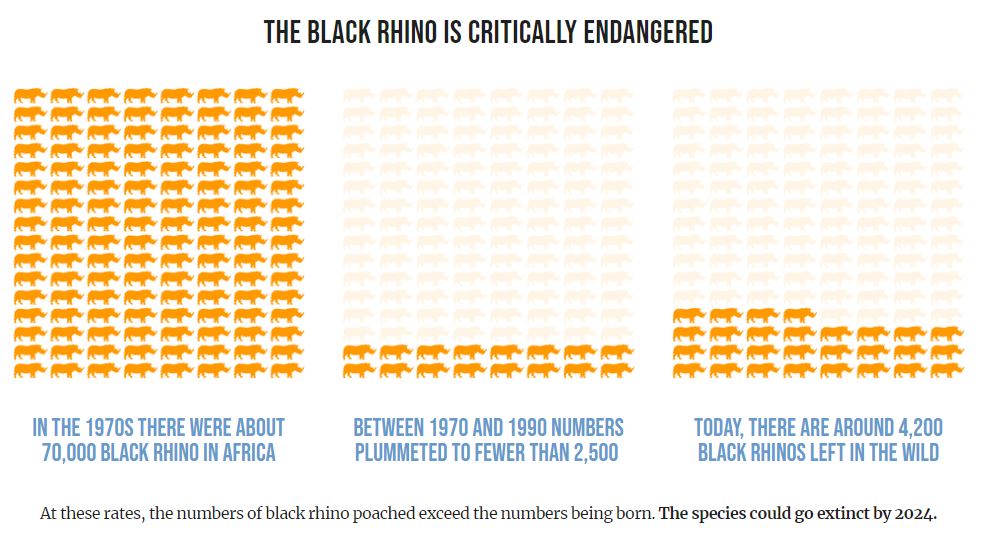

The Sumatran and Javan rhinos are just about gone with less than a 1oo remaining of each in the wild. And the Black Rhino numbers have plummeted since the 1970s (Source):

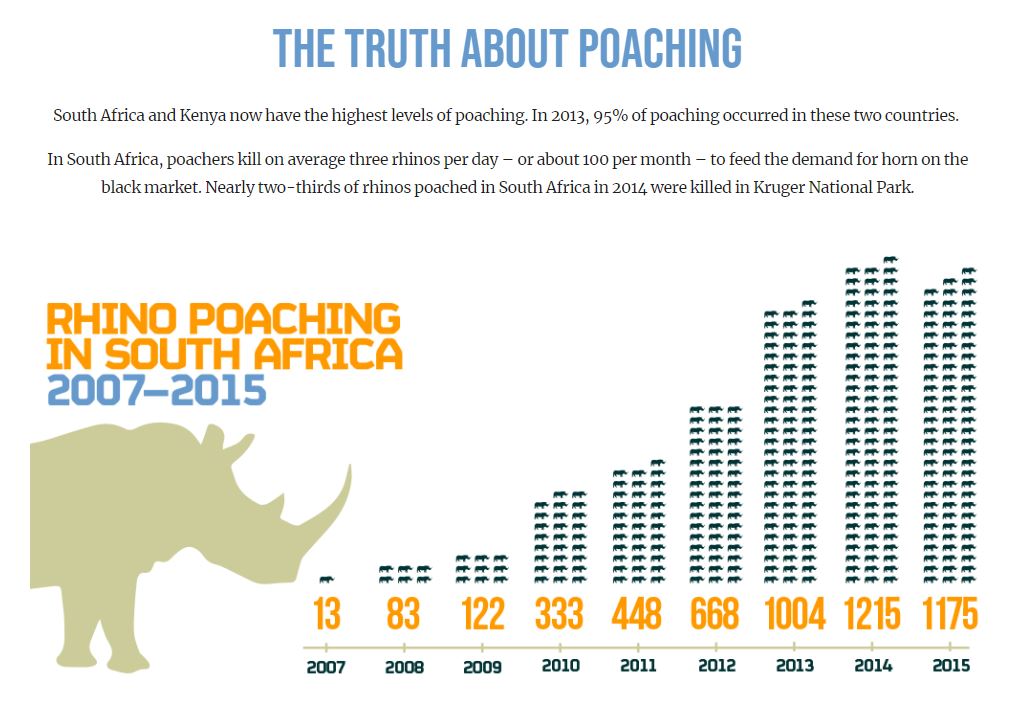

South Africa is an important country for rhinos with 80% of the world population living there. Look at the trend in poaching since 2007!!!!! (Source)

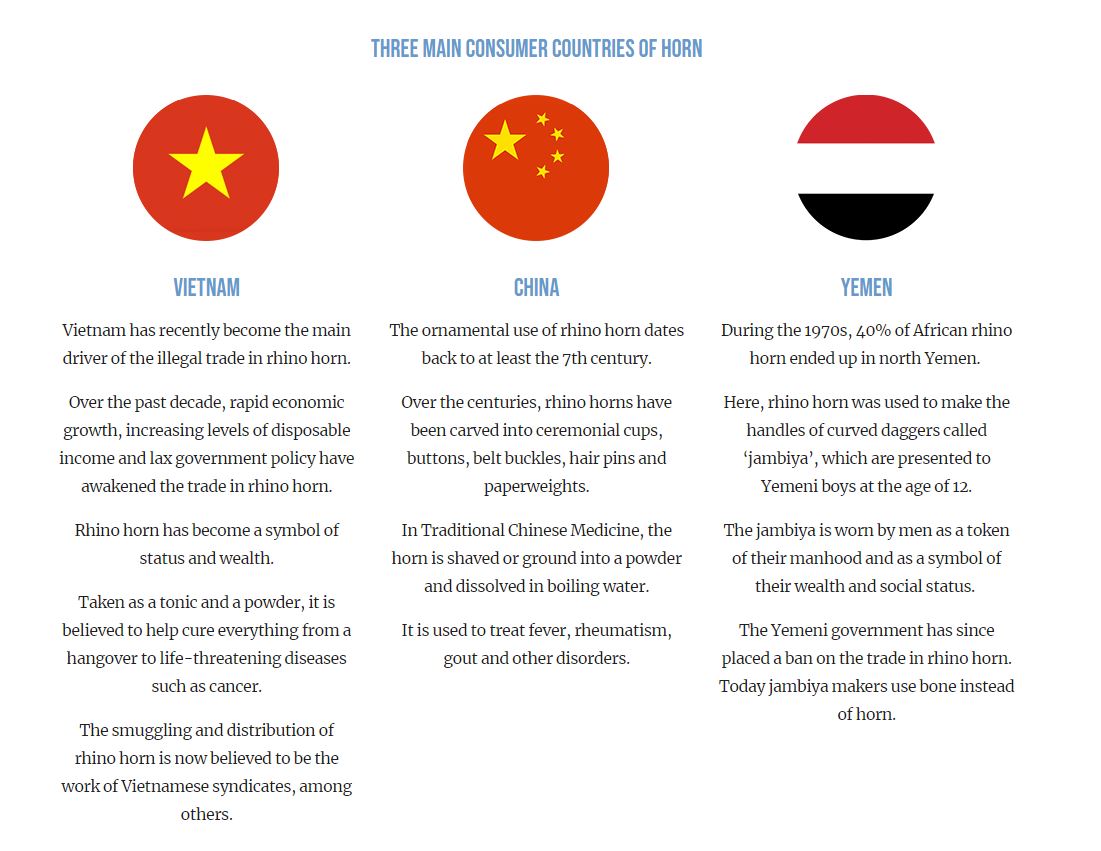

We are killing the rhino for its horn. The main culprits are Vietnam, China, and Yemen. (Source)

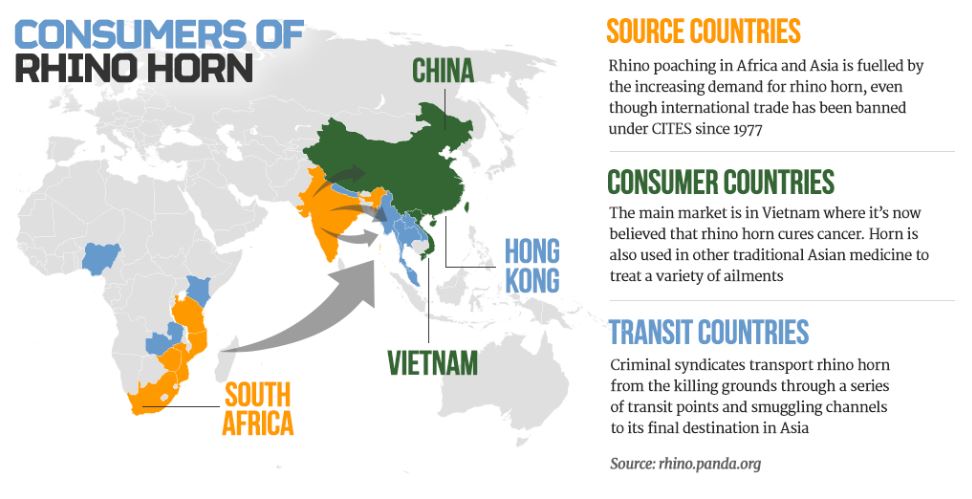

This is where we need to direct our anger to stop this insane slaughter. (Source)

I find the data in these graphics to be powerful, but the image below knocks the wind right out of me. There are two sub-species of Africa’s White rhino — the Northern White Rhino (NWR) and the Southern White Rhino (SWR). The NWR lived in Uganda, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Democratic Republic of Congo. The SWR can be found in South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Uganda). In this image, we see the world’s last male Northern White Rhino. He died on March 19, 2018. Only two more remain on the planet, and they are both female.

So this sub-species of rhino is now functionally extinct. There were about 500 NWRs left in the 1980s but poachers killed them until these last three remained. His name was Sudan, and he lived under armed guard in Kenya. He died of old age, and one of his guards is seen here saying goodbye just before he passed away. This image captures the last of his kind.

What else can one say?

Until next month…..m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, (@ f/8) 1/500 sec, ISO 640, +0.5 EV

30

Shot of the Month – September 2018

Ahhhh, isn’t it beautiful? What a lovely, albeit frightfully dangerous, scene.

Say what? Dangerous? How could this tranquil spot be dangerous? Where are we?

This image was taken at Reflection Lake in Washington State. What is said lake in fact reflecting? Why that would be Mt. Rainier — the state’s tallest mountain with a summit reaching just over 14,000 feet. This lake is a tourist and photographer favorite as it can offer a wonderful view and reflection of this epic mountain. An image of Mt. Rainier from this vantage point is pretty much a portfolio requirement for any nature photographer visiting the area. In late summer one can include blooming wildflowers in the shot as I have done with the image above to add a dash of color to the composition. Sunrise is the best time to shoot from this spot as the water is most calm at this time of the day and offers the best chance for the still water needed to capture the reflection of the mountain. Soon after the sun is up the the water’s surface begins to ripple with the stirring winds and the iconic shot will often be gone until the next day.

Yeah, yeah, all very interesting, but what about the d-a-n-g-e-r-o-u-s part??

Are bears or cougars lurking nearby? No, no cougars but there are black bears in the park but they are not much of a risk. It turns out that Mt. Rainier is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world. Who knew?!! The mountain is so dangerous that it is on the Decade Volcanoes list — this is the list that all bad-ass-wanna-be volcanoes aspire to be on. Mt. Rainier is on the list because it has a great deal of glacial ice — an eruption could create massive lahars that could threaten large population centers near the city of Seattle.

Lahar? Yeah, me neither. Lahars are a violent type of mudflow made up of a slurry of pyroclastic material, rocky debris, and water. They can have the consistency of wet cement when moving. These flows can be super fast, potentially reaching speeds of 60 mph, and may be hundreds of yards wide and up to almost 500 feet high. These massive, fast flows can wipe out any structure in their path and provide very little time to react offering little chance to get out of the way of this wet cement freight train. You can’t outrun a fast-moving lahar…

Wow, so it seems that I just barely escaped the jaws of death. Who knew that landscape photography could be so risky? I may go back to photographing lions and jaguars where it is safe…

Until next month…michael

Nikon D4S, Nikon 17-35mm (@17mm), f/16, 1/15 sec, ISO 400