28

Shot of the Month – February 2021

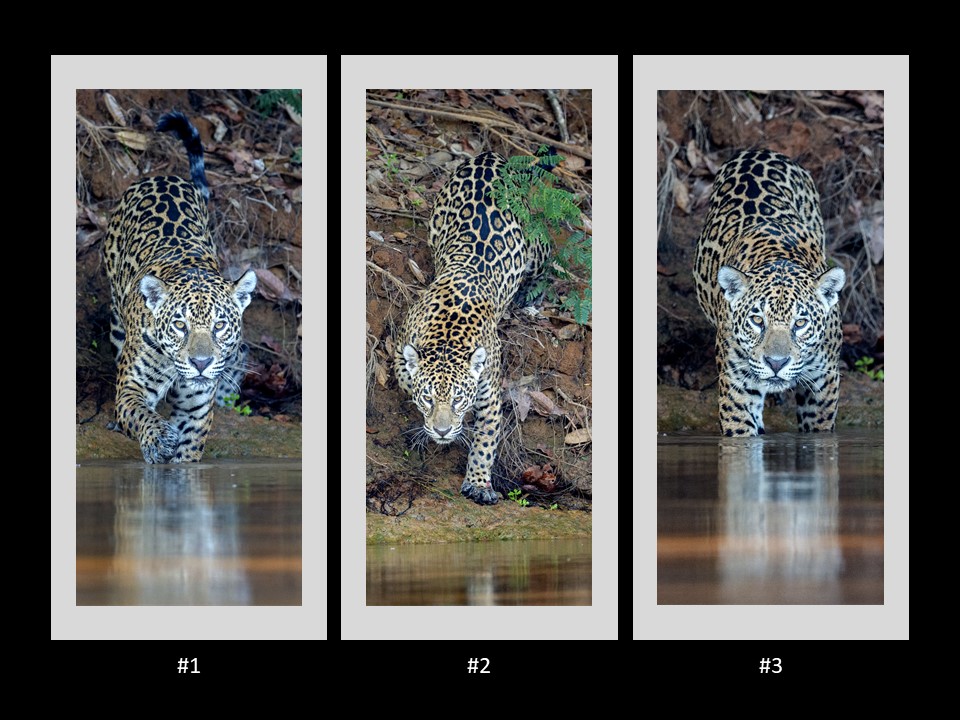

I have been wanting to post one my portrait oriented images of a jaguar for quite a while but found myself on an endless merry-go-round. I will post this image. No, this one. Hmmn, perhaps this one. Repeat ad nauseum.

I found myself faced with a “Sophie’s Choice.”

Sophie’s choice refers to an extremely difficult decision a person has to make. It describes a situation where no outcome is preferable over the other. This can be either because both outcomes are equally desirable or both are equally undesirable.

To be clear, I am not complaining — having three pretty decent images of a jaguar to choose from is a lovely conundrum to be faced with.

Our kitty carousel looks like this:

All of these images were taken in the Pantanal in Brazil. We had the good fortune of watching this female as she stalked the river’s edge in search of a meal.

Image #1:

The eye contact is pretty good but the kicker is the raised paw just about to enter the water.

Image #2:

We trade full eye contact for a menacing stare, but we do get a wonderful full-body view of those gorgeous jaguar markings. And the powerful, yet lithe, almost serpentine shape of the body – it just oozes lethal predator on the prowl.

Image #3

We find ourselves face-to-face with a jaguar. I could lose myself for days in those big ol’ eyes. And we have another good view of that stunning fur coat.

Which one would you take home?

Until next month……m

Settings for #1:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/800 sec, ISO 2800

31

Shot of the Month – January 2021

Bighorn sheep are sheep. With big horns. And scientists refer to these creatures as, wait for it, Bighorn Sheep (BHS).

Lone, slow clap. Clap………………………………..Clap……………………………….Clap……………………….Clap.

How lazy are these scientists? Zero points for creativity.

The BHS males are called Rams. And they do, in fact, ram,

ram; verb: to strike with violence : CRASH

but we will get to that in a bit.

BHS live in the western mountainous regions of North America and can be found from the Rocky Mountains of southern Canada down to the deserts of the American Southwest. These mountain dwellers have split hooves and rough hoof bottoms giving them tremendous grip as they bound about along steep rocks and narrow ledges. Lambs are typically hunted by coyotes, bobcats, gray foxes, wolverines, jaguars, ocelots, lynxes and golden eagles. BHS of all ages are hunted by black bears, grizzly bears, wolves and especially mountain lions who are likewise quite agile even in the uneven, rocky habitat home to most BHS.

BHS live in social groups but the males live in bachelor groups while the females (Ewes) live with other females and their young. Males leave their mother’s group when they reach 2-4 years in age to join a bachelor group. Ahh, those were the days….(not really).

It is only when it is time to mate (the “rut”) when the two sexes come together. And this when the show kicks off. Just before the mating season, “pre-rut”, the males begin to battle for dominance. Only the most powerful ram will earn the right to mate with a group of ewes. And that’s where those glorious big horns come into play. Two competing males will walk away from each other and then turn to rear up on their hind legs and hurl themselves at each other ending in a mighty head bash.

In the image above you can see two rams in just this pose. Did you notice that the guy on the right actually has 3 feet off the ground to maximize his height and momentum? I photographed these two bruhs in the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming.

The resulting collision can often be heard up to a mile away. I can attest that that noise is startling and sounds like a rifle going off. Those horns can weigh up to 30 pounds and equal the entire weight of all the other bones in the male’s body. This Ram Bam session can last for hours until one male finally gives up and unceremoniously just walks away. “I’m out…”

Below, if you look closely you can see that the guy on the right is so chill that he still has a piece of grass in his mouth. Now that’s gangster. Full impact in about 0.2 seconds…

Dominance hierarchy is based on age, body size and horn size so usually the older males, typically those older than seven years old, tend to monopolize mating. Wait your turn, sonny boy…

Pre-match stare down….. “Bruh, you wanna go??!

After this glare they walked past each other and launched their attack.

There you have it, the Bighorn sheep….Bruh culture at its most sheepish. Bam!

Until next month…..m

Nikon D5, Sigma Contemporary 150-600mm (@230mm), f/8, 1/4000 sec, ISO 720, EV -0.333

Want more information (and similar bad jokes)? Check out some of my previous Posts on Bighorn Sheep:

Sources:

31

Shot of the Month – December 2020

I am on record as being a big fan of otters. When I think of “otters” I think of a collection of rambunctious weasels with an endless appetite for fun and group cuddles. Otters are C-U-T-E. Surely you recall this epic video that was all the rage a few years ago (23 million views and counting…).

There are 13 species of otters around the world and many are about two to three feet in length. And generally adorable. Mother Nature decided to supersize one of the three species found in South America and the result was the aptly named, Giant Otter. The Giant Otter (GO) can reach six feet in length and can weigh up to 70 pounds. They are also rather terrifying.

Pop culture analogy: Most otters are to Mogwai (Gizmo) as the Giant Otter is to Gremlin (Stripe). A bit rusty on your Gremlin folklore? You can find a refresher here, and also here on the breakout 1984 film.

Most Otters Giant Otters

I realize that this may seem a bit harsh, but your honor, I would like to submit People’s exhibit ‘A’ into evidence.

Wow, that is a heck of a menacing glare. The Giant Otter is thrashing an eel that he just caught.

Wow, that is a heck of a menacing glare. The Giant Otter is thrashing an eel that he just caught.

Like most otters, the Giant Otter lives and moves about the waterways in a family group as big as 20 strong though the average group size is four to eight. Below is an image I captured of a family resting on a river bank:

In the water giant otters are fearless and will attack ANY creature that poses a threat. In this video, a family attacks and kills a caiman (similar to a crocodile). I present Exhibit B for the court demonstrating the scariness of the GO.

Those shrieks, gurgles, and whines are the fodder for many a nightmare.

And for Exhibit C as to how gangster Giant Otters are, I submit my own testimony. One day while on a boat in the Pantanal, I saw a male jaguar wading through the water near the river’s bank. This is a common hunting technique as the jaguar looks for unsuspecting prey, whether it be caiman, capybara, or even fish in the river. In the other direction, we saw a lone giant otter swimming along the bank on a direct collision course with the jaguar. I got my camera ready as I imagined I was about to photograph a jaguar killing a giant otter. To my surprise, once the jaguar saw the otter he instantly jumped out of the river on the bank. He wanted NOTHING to do with that otter. I imagine if he realized that the otter was by himself he would have tried to stalk it, but he didn’t stick around long enough to find out. Even the mighty jaguar will not take on a group of giant otters in the water. Here you can see a family of giant otters scare off a young jaguar:

The jaguar holds the crown as the top apex predator in South America as a lone giant otter is no match for the 200-pound cat. However, once mobilized a family of giant otters has no rival. Locally the otter is known as “Water Wolf” or “River Wolf.” In Brazil, the giant otter is called ariranha which means “Water Jaguar” in the local Tupi language. Giant Otters primarily feed on fish, as shown in my original photo but they also dine on crabs, turtles, snakes, and small(ish) caiman.

And finally, with this image, Exhibit D. When these guys got supersized they became rather gargoyle-esque in their look. Try not to look at those googly eyes….and those webbed claws……eeek.

Despite their ferocious look and ruthless approach to outsiders, giant otters are affectionate with each other and the entire family is responsible for raising and protecting the pups. I recommend admiring the largest member of the otter family from a distance because if one happens to get too close, make no mistake, these river wolves will cut a b*&#h.

Until next month….michael

Sources:

International Otter Survival Fund

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 180,

30

Shot of the Month – November 2020

I initially titled this blog post “Cocoi Heron” as that is the name of the beautiful bird in the image. But even as I typed out the letters, C-o-c-o-i H-e-r-o-n I knew that that title did not capture the real essence of the shot. When I came upon this scene I gasped, not because of the bird, but because of the L-I-G-H-T. Many nature photographers talk about “chasing the light” to capture the occasional special image.

I am forever chasing light. Light turns the ordinary into the magical. (Trent Parke)

I found this bit of magic in 2019 as we visited the Pantanal in search of jaguars (video). Each morning, just before sunrise, we would load our gear into our small skiff and begin to cruise the rivers in search of wildlife. On this morning we came around a bend in the river and I gasped when I saw this scene. The light was stunning — I instantly reached for my camera as I signaled our “captain” to stop the boat immediately. The soft, delicate glow of the low-morning light perfectly lit the heron as he searched for a meal. I also loved how the heron was separated from the background giving the image a real sense of depth. These are the types of settings that nature photographers spend hundreds of hours searching for and they often only last a few moments each day.

Another axiom of nature photography is that good things often come to those who wait. A great technique to see wildlife is to simply stop in one place and let nature unfold before you. In this case, we stopped for a few minutes to allow me to shoot the scene with a variety of compositions. After shooting multiple shots in a landscape orientation I rotated my camera 90 degrees to shoot in portrait mode. At this point, I wanted to explore that wonderful reflection of the heron on the water. As I was shooting the heron suddenly plunged his head into the water and speared a fish. By pure luck, I had the entire scene already perfectly framed for this action (a very rare event indeed) and I only had to hold down the shutter button to capture the sequence. We witnessed this great behavior only because we stopped and spent some time with the bird.

On another day we found the same heron in some soft light that allowed us to really see his beautiful markings and colors and the wonderful detail of his feathers.

Those of you living in North America can be excused if you thought this was a Great Blue Heron – the two birds are almost identical and make up a superspecies. The Cocoi Heron however is only found across most of South America.

So in short, the improved title for this post pretty much sums up my lot in life — I’m just a dedicated “light chaser.” When I am not working you know where to find me — I’ll be out in some field, swamp, forest, or jungle chasing the light, looking to capture that fleeting magic that illuminates life at its most glorious. Let the chase begin!

Until next month….michael

Sources:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 500

31

Shot of the Month – October 2020

By 2020 I imagine that most people have heard about the bumble bee crisis — this vital insect has been declining rapidly in the last 30 years due to the use of pesticides, climate change, and loss of habitat. Bumble bees are essential pollinators and without them, many ecosystems may collapse not to mention the 15 billion dollar agricultural industry which needs them for pollinating crops.

If those challenges weren’t daunting enough the poor fuzzy bee must also take care to avoid the Goldenrod Crab Spider (GCS), shown above, as they are particularly fond of dining on bees and wasps.

The GCS can typically be found hiding on an assortment of yellow or white colored plants though they can be occasionally found on purple thistles and asters and plants of other hues. Preferred hunting perches include milkweed, trillium, white fleabane, ox-eye daisy, red clover, butter cups, and, of course, golden rod to name a few. I found the lovely female GCS above in our garden on a black-eyed Susan in late summer.

The body of the GCS is naturally white though if she is hunting on a yellow flower she can change her body color with an incredible level of accuracy to match the color hue of the plant. The color transformation is not automatic and going from white to yellow takes between 10-25 days while converting back to white only takes about 6 days.

I found this white GCS on a sunflower in a different part of the garden:

Crab spiders get their common name from their tendency to hold their front legs aloft like crabs (like in the image above), and their ability to run sideways as well as frontwards and backwards. These spiders do not spin a web to catch their prey but rather are ambush predators. The spider will sit patiently on the flower until an insect comes too close and then she will snap those legs around the body of the prey as she sinks her fangs into the victim and injects them with a paralyzing venom. Sometimes the spider will try and blend in while other times, if there is a color mismatch, she may sit in the middle of the flower imitating the blossom.

A honeybee in the grasp of a Goldenrod Crab Spider:

Female GCS range in size from 1/4” to a bit more than 1/3″ (body length only). Males are smaller and range from 1/10″ to 1/6″ in size. During the bounty of summer, these spiders will eat just about any insect including flies, bees, butterflies, grasshoppers, dragonflies, and hoverflies. However, by late summer and fall most species of bees have died off and many insects are gone. Except for bumble bees. They continue to thrive and they are the primary visitors to the now-blooming fields of goldenrod, thistle, and other late-blooming flowers. They also become the primary prey for the GCS. During the fall, goldenrod-filled meadows become killing fields and are littered with the bodies of common eastern bumble bees.

Pollinating is a dangerous business…

Here you can see a live hunt in action (link). (Volume up for full effect!)

Bee safe out there. Until next month….m

Sources:

Sharp-Eatman Nature Photography

Nikon D850, Nikon 105mm, f/6.7, 1/30 sec, ISO 64, 3 shot focus stack

30

Shot of the Month – September 2020

For eleven glorious days in September 2020, we explored the Grand Teton NP (GTNP). The photo above was one of the best images from that trip, though, uh, it was actually taken in Yellowstone NP. Say what? Let me explain…

During our first four days in the GTNP, we had some wonderful sightings — moose, lots of moose, and bison, pronghorn, owls. Fantastic stuff.

At different locations, we would invariably bump into other photographers and tourists. People would talk about what they had seen and share information — we were all looking for the next hot tip on where to find something special.

On the fifth day, the chatter was abuzz about a grizzly bear that had killed an elk in Yellowstone.

“Did you hear about the Grizzly?

“No”

“Yeah, a woman got it all on video. It is amazing. The bear is still with the elk on the bank of the river.”

More and more chatter about the video that was on Facebook. And then we would bump into people who had been there and seen the bear with the kill. They said it was incredible.

The kill happened on a Friday. We heard about it on a Saturday. We (my partner Nicky and I) discussed…”Should we try and go up to Yellowstone to see the Grizzly…”? We figured that a grizzly would finish the elk quickly so till we got up there he would probably be gone. We stayed put.

Sunday, people are still talking about the grizzly…We discussed again: “Should we go…”? In the end, no.

Monday. People are still talking about the grizzly. “Yeah, the bear is still there…there is still lots of meat on the kill…”

We again pondered this “High Risk-High Reward situation.”

What made it high risk?

- We would arrive 4 days after the kill was made. It seemed very unlikely that a grizzly would stay so long on a kill site — how much of a meal could be left to entice him to stay longer? We could drive up to the site and find nothing. The area between GTNP and Yellowstone is a dead zone for wildlife so there is not much to see otherwise. Sure, we could wander around the lower part of Yellowstone and hope to see wildlife but the odds of seeing something good were low otherwise.

- It would take 2.5 hours to reach the kill site. We heard that parking was very difficult so we would have to arrive early or we wouldn’t be able to park near the site and we would have to walk a long distance. And as a photographer, I would want to arrive early to have the good morning light. We would have to get up at 3:30 am to reach the nearest parking area by 6:30 am (just before sunrise). This meant that we really should end our day early on Monday so we could get to bed early, costing us photo opportunities on that day. Tuesday might be a complete wash. We would most likely get back late on Tuesday making it difficult to get out early on Wednesday, and in general, leave us exhausted for 1-2 days. So this high-risk “detour” could cost us 2-3 days of photography at GTNP.

- Would the light be any good at the location? Backlit?

- Would we have access to the site? In some settings, only a few photographers have the best, unobstructed angle for a good shot.

And the high reward part? Well, getting to see a grizzly on a kill site is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

What to do? Getting a good photo out of this venture seemed very, very unlikely and would cost us a lot of time and degrade our ability to capture images in GTNP. But, a grizzly, on a kill site….we had never had a good grizzly sighting before.

We pushed all of our chips into the center of the table and rolled the dice (Craps metaphor). We got up at 3:30 am and drove the entire length of GTNP in the pitch black (this is nerve-racking as you never know when an animal might come out onto the road), through the border area between the parks, and then up through the southern part of Yellowstone to Hayden Valley. We found the parking area and we tucked into the next-to-last spot! We spoke to a few people and understood where to go. We walked along the river and found a spot about 150 yards across from the grizzly. Photographers were spread out along the river bank but there was plenty of space for everyone so it was not quite as crazy as it can be sometimes.

And then we waited. The river was completely fogged in. It took more than 2.5 hours for the fog to burn off before we could start capturing images.

Was it worth it? Wow, was it! Once the fog burned off we had a clear view of the grizzly. The location of the bear on the river was near perfect and was well-lit in the morning and in the afternoon. We spent 12 hours there taking it all in.

It was just an amazing experience to get an unobstructed view of a grizzly for such a long period and observe his behavior and the interactions between him and other wildlife as he fed and protected his kill.

So first, here is the video showing how the grizzly killed the elk. September is the rut season for elk and this massive bull was in the prime of his life. Unfortunately, the bull had broken his rear leg, most likely while sparring with another male. The grizzly must have noticed this injury and took immediate chase. Death was relatively quick as the bear drowned the elk in the river.

And in this video, you can see how much work the grizzly did to bury the elk to protect it from scavengers.

The bear’s day was comprised of digging up the carcass to feed and then burying the carcass to keep it safe. Then digging it up…then burying it. Digging…burying. Dig. Bury. All day. He was also relentless in his efforts to chase off any scavenger that might try and steal a morsel. So many words…check out this fun video that Nicky captured. It will give you a better sense of what our day was like:

Kind of hard to steal a bite when a 600 lb. grizzly is lying on the prize…

By burying the carcass next to the water the bear only had to defend in one direction. In this scenario not even an entire pack of wolves would be able to budge this bruiser. This one, plaintive-looking wolf is not a threat, and the bear never even bothered to growl or threaten the wolf as the balance of power was clear.

We finally left to drive back to GTNP at 7 pm and made it to bed by midnight. A 20+ hour day. We were pretty shattered the next couple of days but the high from that dice roll will last a lifetime.

Until next month…..michael

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm,1.4x TC (effective 850 mm), f/5.6, 1/640 sec, ISO 1100

31

Shot of the Month – August 2020

Photographers love hitting the beach to capture, what they hope will be, an epic image of where land and sea collide. Photographers on the East Coast of the US usually get up early to capture the sun rising on the horizon. Dawn’s early light and whatnot.

Light chasers on the West Coast typically make it a late evening as they wait by the sea for the sun to paint the sky red as it glides into the ocean.

Having moved to Washington State I am now exploring West Coast seascapes — a new paradigm for this East Coast “kid.”

In September 2019 I made my first visit to the Oregon coast to photograph the shipwreck of the Peter Iredale. You can read about that adventure here. I visited the beach in the afternoon and captured these lovely images:

Standing with my back to the ocean the setting sun painted the rusting hull with a beautiful hue of red and pink light.

In August of 2020, I went back to the same beach but I only could visit the site in the morning. Given that the sun would rise from the other side (the “land” side) the colors would be much more muted. Would it be worth going? Perhaps better to just sleep in? In the end, I dragged myself out of bed at 4:30 am and made my way to the beach. Grumble, grumble. Voice in my head: “…you’re just wasting your time….” Grumble, grumble.

Before the sun breached the horizon I captured this ok shot:

As the sun rose over the horizon I explored how the warm light moved down the ship’s hull:

Yawn. While accurate, not terribly compelling…

I continued to look down at my camera as I shot the changing light. After a few minutes, I looked up and glanced behind the hull.

“Holy S*&T!”

I had totally NOT noticed that the sunbeams were now just high enough over the horizon to blast beams of light through the ship, casting dramatic shadows. This caught me completely off guard. I hadn’t even imagined such a scenario. Frantic, I ran over to the other side of the ship and began to shoot into the sun. I knew we had the potential for something really special with this scene.

For the next 20 minutes, I worked at a feverish pace to capture the changing light and shadows before they vanished….First some color versions:

The harsh light and dramatic setting are well suited for Black and White…

Which version do you like best? (#1?….#6?). (I am leaning toward #4, myself)

So there you have it, another example of why you should always go out and see what Mother Nature has up her sleeve.

Conventional wisdom says,

West Coast Beach = afternoon shoot. (for the “ideal” shot)

But as we can see here, even a sunrise, on a West Coast beach, can offer a glorious scene when the conditions are right.

Shifting the sun 180° can create scenes that are as different as, well, night and day….which seems kinda obvious, now that I say it out loud.

Still caught me off guard though…

Until next month…m

Image #4: Nikon D850, Nikon 17-35mm (@ 35mm), f/22, 1/1000 sec, ISO 64, -1.0 EV

31

Shot of the Month – July 2020

In October 2019 I made a quick, mid-week run down to Oregon (Portland is about 3 hours away) to work on my landscape photography skills. I mainly shoot wildlife so I need all the practice I can get. I had visited some of the waterfalls of the Columbia River Gorge in the summer and I wanted to see if autumn brought any interesting color to the compositions. On this quick run, I only had Wednesday afternoon and Thursday morning to make images – not much time but my goal was to try and get at least one good photo from the trip. The falls can get quite busy on the weekends so I went down in the middle of the week to, hopefully, avoid the crowds.

Late Wednesday afternoon I hiked up to Ponytail Falls and found the place deserted. Ahhh, heaven. I could commune with nature and compose my shots in peace. I consider the trip a booming success having created this image — not bad for a wildlife guy!

I had to shoot two images to get the entire scene in sharp focus. In the first image, I focused on the rocks in the foreground (leaving most of the scene behind blurry) while in the second image, I focused on the rocks about 2/3rds back in the scene (which left the rocks in the foreground blurry). By merging the sharp elements from the two images together we get one image that is sharp from front to back.

A great way to improve your landscape images is to ensure that you have a strong element in the foreground of the image. In this case, I used the rock in the lower left corner to anchor the photo. The key to a compelling image is depth and this image has multiple layers — the rocks in the foreground, then the stream, the rocks and bushes a bit further back, then the falling water, and finally the rocks of the cliff face.

Truth be told I did place the yellow maple leaf on the rock — it was lying just next to the rock but I positioned it on the rock for better viewing as it helps tell the story and it is visually compelling. I tried positioning the leaf in multiple places and in various orientations. In the end, this composition worked best – I like how the leaf stem guides your eye into the rest of the image. I had started with “stem down” but it all clicked when I rotated the leave around into the “stem up” orientation. I also like how the yellow leaf mirrors the yellow leaves on the bush in the far back right portion of the scene.

Together, these elements convey “Falls in the Fall.” Just what I was looking for…

Until next month…..m

Here are a few links with ideas on how to improve your landscape compositions:

Importance of Foreground Elements (Video)

5 Landscape Mistakes to Avoid (Video)

How to get a perfect foreground (Article)

Importance of foreground in landscape photography (Article)

Nikon D850, Nikon 17-35mm (@ 17mm), f/8.0, 1.5 sec, -0.5 EV, ISO 64

29

Shot of the Month – June 2020

Warning: Objects on your screen may be smaller than they appear.

In this image, the American Pygmy Kingfisher (APK) appears to tower over us. Fear not, we are not in danger. The APK is the smallest of all kingfishers and is about 5 inches in length and tips the scales at a mere 18 grams (about the weight of 3 American quarters or about 1/2 an ounce).

The wee bird seems so large because I was floating underneath him in a boat at a close distance with a 400 mm lens when I captured the image. I love this shot as the combination of side lighting and blurred background gives the image an other-worldly, mystical vibe.

APKs can be found in the lowlands of the American Tropics from southern Mexico to central Brazil. They are most commonly seen along small woodland streams, pools, puddles, and small channels in mangroves. You can see their full range here. I photographed this fellow in the Pantanal in Brazil.

The head and wings of the APK are metallic green while its body and neck are deep orange-buff, shading to rich dark rufous on the breast, sides, and flanks. The diminutive kingfisher sits by rivers and will dive headfirst into the water after small fish and tadpoles. He will also dine on insects such as cockroaches, aquatic beetles, and larvae.

Chillin by the river:

Scanning the water below…

Uh, too close!

Smallest of kingfishers = Largest of smiles

Until next month….m

Nikon D500, Nikon 200-400mm (@400mm), f/4, ISO 160, +0.5 EV

Source:

30

Shot of the Month – May 2020

On our first trip to the Pantanal in 2017 we learned that this incredible ecosystem was home to five types of kingfishers. I am a sucker for bold colors so I was hopeful that I might capture a few on “film.” While I was hopeful I was not optimistic, as most kingfishers are tiny and skittish making it very difficult to capture a good image. Seems that they do things differently in the Pantanal. On our first day on the water, during a three-hour boat trip on the Pixaim River we saw ALL five species. And even better, the birds often took no notice of us as we drifted by as they scanned the water below for fish. On our second trip to the Pantanal in 2019 I captured the image above of a male Green Kingfisher (GK). The female GK looks similar though she does not have the rufous colored chest feathers.

Small fish are the mainstay of his diet so you can usually find the GK perched on a low-hanging branch near the water’s edge as the bird looks for fish that swim near the surface. Aquatic insects are also on the menu.

Target acquired, Dive!

Target missed! Time to shake it off and get back in the game.

The Green Kingfisher can be found from Southern Texas through most of Central and South America. Their numbers are dropping in Texas due to loss of habitat but they are still plentiful further south. To raise their young GKs build a horizontal tunnel into the side of the river bank. The tunnel is about three long and about two inches wide. (Two inches wide – that gives you a sense of how small these birds are)

This kingfisher, Chloroceryle americana, for you science types, is a real beauty and surely leaves the other birds green with envy.

Until next month…..m

Sources:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 720 (Shot in Manual Mode with Auto ISO)