31

Shot of the Month – March 2022

Travel to the high desert of Eastern Oregon and you can gaze in wonder at the Painted Hills as shown in the image above. These mellow, albeit colorful hills are a time capsule of a tumultuous past that is hard to fathom. Believe it or not, this place was once a tropical forest that was thick with vegetation, palm trees, bananas, and avocados. The area would get 80 inches of rain per year — this desert now only receives about 15 inches of moisture a year, mostly in the form of snow.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let’s start at the beginning — waaaay back. This epic tale began 35 million years ago when massive volcano eruptions in the Cascade Mountains, a hundred miles to the west, blanketed this area with ash and pumice. Over time the ash and sediments were mixed by natural processes including the flow of water, growth of plants, and the movement of animals. The surface ash was oxidized over the passing eons. Buried under new layers and deposits, the ash turned into soils by way of compaction and cementation. With more time and weathering, the exterior surfaces of The Painted Hills were worn into clay. Now, they are primarily made of hard claystone layers.

Over the millions of years since those first eruptions, the area has experienced wild shifts in climate. Millions of years ago this space was home to weather more like Costa Rica – the tropical forests I mentioned earlier. Over time the climate shifted again and the area became a grassland with oak and maple trees. Those stunning colorful red, yellow, and black stratifications in the hills above are a signpost of each different climate reality.

The red stripes are laterite soil that was formed by floodplain deposits when the area was warm and humid. The darker black soil is lignite which was vegetative matter that grew along the floodplain. The yellow soils were formed during dryer, cooler climates. With each new climate, the landscape dramatically changed bringing different types of vegetation, water levels, temperatures, and animal life. Areas near the Painted Hills are rich with fossils from plants and animals – one can find fossils of saber-toothed cats, early horses, camels, and rhinoceroses to name just a few.

Standing on this quiet overlook, it is hard to comprehend the scale and breadth of the cataclysmic changes this land has seen.

These hills strike me as a powerful reminder that when we meet a hill, or a person, what we see today does not tell their entire story – they may have had a past, and may have a future, that is wildly different from today’s snapshot. Likewise, we can only imagine what they may have endured, for better or worse, to reach their current state.

Until next month…

Sources

If you want to photograph the Painted Hills here are a few good guides:

Here is a great overview on visiting the Painted Hills: Painted Hills of Oregon: Everything You Need To Know

Another guide: Exploring Painted Hills, Oregon

Another good guide: A Stunning Guide to Oregon’s Painted Hills

Nikon D850, Nikon 24-120mm (@35mm), f/8, 1/90 sec, ISO 64

28

Shot of the Month – February 2022

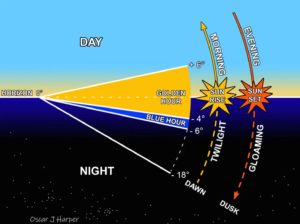

If you have any nature photographer friends you may have heard them talk wistfully about the “Golden Hour.” It is that special time of day just after sunrise or just before sunset when the light takes on magical hues of red, orange, or yellow and has a certain softness that seems to gently caress whatever it falls upon. During “Magic Hour” the sun is low in the sky, only a few degrees from the horizon.

The lesser-known cousin of Golden Hour is Blue Hour. I kid you not – it really is a thing. To explain it I have to get a bit astronomical-like, so strap in. And, uh, bring along your protractor…

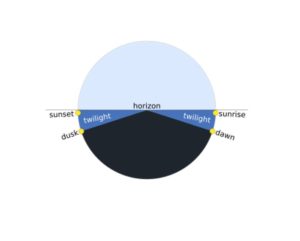

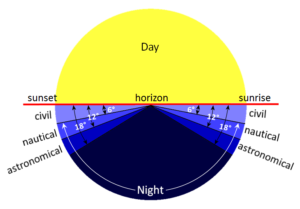

At its simplest, Blue Hour takes place during twilight. I have heard this term my whole life but what exactly does it mean??

Twilight is the time between day and night when there is light outside, but the sun is below the horizon. During this period the light we see does not come directly from the sun but rather is scattered and refracted from the upper atmosphere down to our eyes.

Now for the more complicated version. Time to break out those protractors (And see, you thought that box in your attic from 3rd grade wouldn’t come in handy. Tsk. Tsk.)

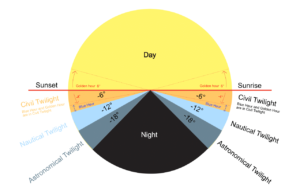

Astronomers were not satisfied with just one “twilight” and created a more precise delineation as shown here:

Let’s break it down.

Astronomical Twilight: The sun is located 12 to 18 degrees below the horizon. In astronomical twilight, sky illumination is so faint that most casual observers would regard the sky as fully dark, especially under urban or suburban light pollution. During astronomical twilight, the horizon is not discernible, and moderately faint stars or planets can be observed with the naked eye under a non-light-polluted sky. In the evening, when the sun is at 18 degrees below the horizon we have Dusk, the end of twilight, and the beginning of full evening darkness. In the morning, when the sun is 18 degrees below the horizon, we have Dawn, marking the end of full darkness as we begin the morning twilight.

Nautical Twilight: The sun is 6 to 12 degrees below the horizon. In general, the term nautical twilight refers to sailors being able to take reliable readings via well-known stars because the horizon is still visible, even under moonless conditions.

Civil Twilight: The sun is located less than 6 degrees below the horizon. Civil twilight is the period when enough natural light remains that artificial light is not (usually) needed.

Still with me? You are probably thinking – “Ok Galileo, this is all mildly (barely) interesting, but where the heck does Blue Hour fit in all this?”

Here ya go:

Blue Hour takes place when the sun is between 4 to 6 degrees below the horizon which is usually about 30-40 minutes after sunset/before sunrise. During this period the light takes on deep shades of blue and can produce unique images. Truth be told the Blue Hour really only lasts about 20 minutes but the duration varies by where you are on the planet.

I like this graphic also (some may find this one clearer):

(Did you notice “Gloaming” in the graphic above? It is just an Old English/Scottish term for twilight)

So that was a lot of blah blah to talk about the Blue Hour — more importantly, here is some of the magic it can work:

In this image we have a herd of giraffes strolling by shortly after the sun has set on the Serengeti plains of Africa (Masia Mara National Reserve in Kenya, to be precise).

Here is what the scene looked like while the sun was still above the horizon (late golden hour):

So, if you want to get your blue on you have to get out there waay early or stick around waay late, and then you have to work fast because blue time flies especially fast.

Now, don’t be blue, but we have reached the twilight of this post.

Until next month…..michael

Sources:

Mr. Reid.org (dawn-dusk-sunrise-sunset-and twilight)

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm, f/4, 1/400 sec, ISO 2000, -0.5 EV

31

Shot of the Month – January 2022

Many photographers love to “fill the frame” when they photograph wildlife. Many spend a tremendous amount of time, energy, and money to have the skills, equipment, and opportunities (photo tours) to allow them to get close to wildlife and capture an image that is filled from top-to-bottom, side-to-side with that fuzzy/furry/scaly natural wonder. Photographers will spend thousands of dollars for the largest lenses to give them the extra reach to magnify their subject.

Yep, all sounds pretty familiar – you can lock me up for this also – guilty as charged.

Our offense is understandable – we love wildlife and such images allow us to see details that one can rarely see with the naked eye. Such close-ups allow us to revel in the beauty of our subjects.

The downside is that you can go online and find thousands, and then many more thousands of images that look more or less the same.

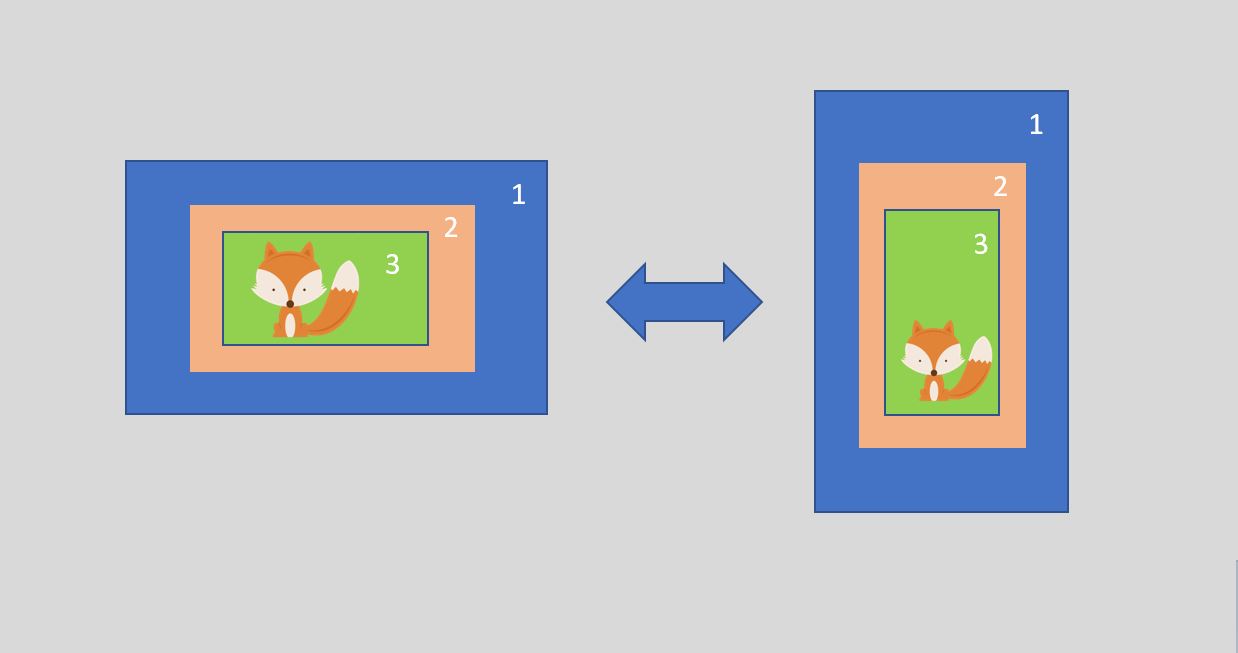

To avoid this common mistake and get beyond the simple “animal portrait” when shooting I push myself to try and get at least 3 shots with different levels of zoom on the subject. And if I have even more time I rotate the camera 90 degrees and take another 3 shots with different levels of magnification. This can be achieved by either moving yourself (those boots were meant for walkin) or by using a zoom lens that can change focal length.

By pulling back I can place the animal in its environment or habitat and tell a more complete story about its life. For example, in the image above I purposely did not zoom in to allow the viewer to see this brutal, albeit beautiful, winter landscape, because it is as important to the story as is the moose. The wider view gives a sense of what life is like for a moose in the winter in the Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) in Wyoming.

Looking at that scene I can’t help but get a shiver down my spine.

Here is another one of my favorite images – by pulling back we see not only a magnificent bull moose but we also get to revel in the colorful bounty of fall in the GTNP.

I rarely share images of moose without antlers (cows, young males, post-rut males) as they usually are not as photographically interesting. In the image below however, the landscape adds so much to the story it becomes a keeper.

So, don’t get me wrong, I love me a great close-up portrait. My point is ok, once you get that shot, now keep going and explore what other stories can be told. The “environmental portrait” is a wonderful way to broaden and deepen the story and connect the viewer to not only the animal but also to the place they call home.

Until next month….m

Nikon D5, Nikon 70-200 mm f/2.8 (@105 mm), f/5.6, 1/180 sec, ISO 140, EV +1.0

31

Shot of the Month – December 2021

Capturing a good image of an all black bird is quite tough. Exposing properly to bring out the detail in the black feathers usually leaves the rest of the image overexposed. This image of a crow, captured in Wyoming, is one of the few times the lighting worked out.

I love the simplicity of the composition and the basic “primary” colors in this scene — simple but bold blue, black, and white. Of course these are not true primary colors – as we know from elementary school the three primary colors are red, yellow, and blue. But I think you get my drift.

I have to also note that I am only about 90% confident that this is a crow, which is a member of the Corvidae family. Also in this family is the Raven which looks very similar though ravens are usually larger, sound a bit different, and have a few other different physical traits. Here is a good video that highlights the key differences and clues on how to identify a Crow from a Raven.

Given the shorter, even-shaped bill, I am going with crow for my image.

As you may have heard, crows are incredibly intelligent and one of the few animals able to use tools. Watch the video below, it is one of my all-time favorites as it clearly demonstrates the mind- boggling problem-solving skills of crows.

There you have it – a bright image of a very bright bird.

Until next month….

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm (@400mm), f/8, 1/1500 sec, ISO 400, -0.667 EV

30

Shot of the Month – November 2021

This month a dash of color to help counter the winter doldrums – here we see a lovely female Ruby-throated Hummingbird investigating the flowering Liatris Spicata (Blazing Star) plant.

You will notice that the wings off the hummingbird are blurred in my images. I actually like this look as it acurately reflects how we see hummingbirds with our eyes. And it adds to the “fairy” look – And what is more fairy-esque than these wee flying wonders?

Hummingbirds are tremendous flyers and can fly horizontally, backwards, vertically and can hover – the smaller the hummingbird the faster the wing beat to keep them aloft. The Ruby-throated humming bird shown here beats her wings about 50 times each second. A rufous humminbird’s wing beat is about 52-62 wingbeats per second. The giant hummingbird of the Andes (about the size of a Cardinal!!) has a wingbeat of just 12 beats/second. The tiny bee hummingbird of Cuba, the smallest bird on earth at just two inches in length, beats its wings 80 times per second. (Source)

Capturing an image of a hummingbird with the wings motionless is possible but requires a very fast shutter speed or the use of one or more flashes. Some photographers are quite adament about taking images of hummingbirds with the wings motionless and will go so far as to create mini “studios” to make it possible. In these setups one puts a feeder on a table or hangs it from a stand, sometimes amongst or behind flowers. From here you surround the area with 4 to 5 flashes set to expose the scene so quickly that the wing motion appears static. Sometimes a painted backdrop is added to ensure that the background color is just right. Quite a bit of tinkering may be needed to deterime the proper location of each flash to ensure that the scene is properly lit. You also need to spend some time to dial in the appropriate power output of each flash to get the right exposure. The feeder is essential to ensure that the hummingbird comes back to the exact same location for the specific lighting setup that you have created. Here is an example of one home setup:

In countries where hummingbirds are plentyful, say Costa Rica or Ecuador, you can actually book a photo tour where the guides will create elaborate hummingbird setups – all you have to do is show up, connect your camera to the flashes and snap away.

It’s all a bit much for me – I am not quite that motivated to get the “perfect” shot of a hummingbird and prefer to take my chances in the “wild.” In the images above I actually did use one flash but as you can see it didn’t do much to help stop the wing movement (I didn’t really know what I was doing).

Here we have a free range Anna’s Hummingbird that I shot with natural light in our garden:

But hey, who I am to judge? If you are passionate about hummingbird flash photography, go for it. If you want more information on how to set up such a setup, look here:

Hummingbird Flash Set-up Guide

And here is a video of a guy that walks you through how he puts together his setup.

And here is an example of a hummingbird photo tour to Ecuador.

There you go – the ins and outs of hummingbird photography. You can go hardcore studio lighting or you can just “wing” it, uh, so to speak.

Until next month…..m

Nikon 300S, Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 (@ 200mm @ f/4), ISO 800 1/250 sec.

31

Shot of the Month – October 2021

Any great image starts with great light. The best light for nature photography can be found when the sun is low in the sky so usually around sunrise or sunset. At those times the light is filled with wonderful warm hues that humans really dig. Common advice for beginning photographers is to position yourself such that your shadow is pointing toward the subject making it “Front Lit.” With the sun behind you the light will fall evenly on your subject and help avoid highlights or shadows that can complicate making a proper exposure. With the amazing technology in modern cameras it is almost impossible to get the exposure wrong on a front lit subject. So even in “Program” mode, where the camera makes all the exposure decisions for you, you are more than likely going to get a properly exposed image.

Any great image starts with great light. The best light for nature photography can be found when the sun is low in the sky so usually around sunrise or sunset. At those times the light is filled with wonderful warm hues that humans really dig. Common advice for beginning photographers is to position yourself such that your shadow is pointing toward the subject making it “Front Lit.” With the sun behind you the light will fall evenly on your subject and help avoid highlights or shadows that can complicate making a proper exposure. With the amazing technology in modern cameras it is almost impossible to get the exposure wrong on a front lit subject. So even in “Program” mode, where the camera makes all the exposure decisions for you, you are more than likely going to get a properly exposed image.

Which is not the same as getting a compelling image.

One critique of front-lit images is that they can be a bit flat and lack depth, especially for landscape images. So while shooting front-lit subjects helps deal with the challenges of exposure, a great image still needs strong composition and/or skilled use of contrast, color, leading lines, etc.

In the image above, late afternoon light is casting a wonderful warm glow on the giraffe. I purposely shot this image from below and waited for the giraffe to reach a point where he would stand tall above the horizon in sharp contrast to the dark, brooding sky in the background. The exposure was a no brainer but we worked pretty hard to find the right spot to wait for the elements of the composition to line up and elevate this front-lit shot to something a bit more special.

Generally you want to avoid shooting in the middle of the day as the front light at this time is harsh and will produce difficult shadows on your subject. Either go home for a rest until the light gets better or explore compositions that will work in black and white.

Outdoor Portrait Tip: Front lighting works well for portraits of family and friends though the bright light can be tough on your subjects. Two potential solutions:

- Once your subjects are in place, ask them to close their eyes. This will avoid burning out their retinas as you set up the shot. Once you are ready ask them to open their eyes and smile. Click. Lovely image with no squinting.

- Find some shade and have your subjects stand there. The even light will work well and no eye strain for your subjects.

When in doubt, use front lighting to get the shot. Once you have that shot, time to explore more dramatic light – back lighting and side lighting. These lighting situations are tougher to expose properly but when done right can provide stunning results.

We’ll shine light on those topics on another day (see what I did there?).

All the best…..michael

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 100, EV -0.667

30

Shot of the Month – September 2021

Is this image Art? And if it is, does that make me an “Arrrteeest”?

Photography was invented in 1826 (almost 200 years ago) and since that time the “Is photography art?” debate has raged on. This may surprise you given that photography is generally accepted today as Art, but this is a fairly recent phenomenon. How recent? Most museums only began to collect and display photographs in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Did you know that there are seven traditional forms of art?

Me neither. Photography is not among that list (scroll to the end to see the original seven).

So what is art? The Cambridge Dictionary says:

the making or doing of something whose purpose is to bring pleasure to people through their enjoyment of what is beautiful and interesting, or things often made for this purpose, such as paintings, drawings, or sculptures

I do strive to bring people pleasure with my images so perhaps I am trying to be an artist. Painting and sculpture use essential elements and principles such as line, shape, form, texture, balance, asymmetric balance, color, size, depth, light, positive space, and negative space.

Hmmn, interesting. I also consider many of these elements when I raise the camera to my eye. In fact, on an outing I may spend hours waiting to get the right mix of these elements in place before taking a single image.

As a photographer I spend much of my time trying to showcase the work of the world’s greatest artist – Mother Nature. Each day she throws together a fabulous mix of flora and fauna draped in captivating colors and hues. Every day, across the planet she is producing one masterpiece after another.

If I do my job correctly and get all the technical stuff right — set the right aperture, dial in the shutter speed, and compose the image well then Mother Nature will do the rest and we get some beautiful images that hint at the wonders of the natural world.

The Merriam Webster dictionary defines art as:

the conscious use of skill and creative imagination especially in the production of aesthetic objects.

I can say that I am a better photographer than I was 30 years ago – even this old dog has acquired a certain level of skill and creative vision to help capture Mother Nature at her best.

certain level of skill and creative vision to help capture Mother Nature at her best.

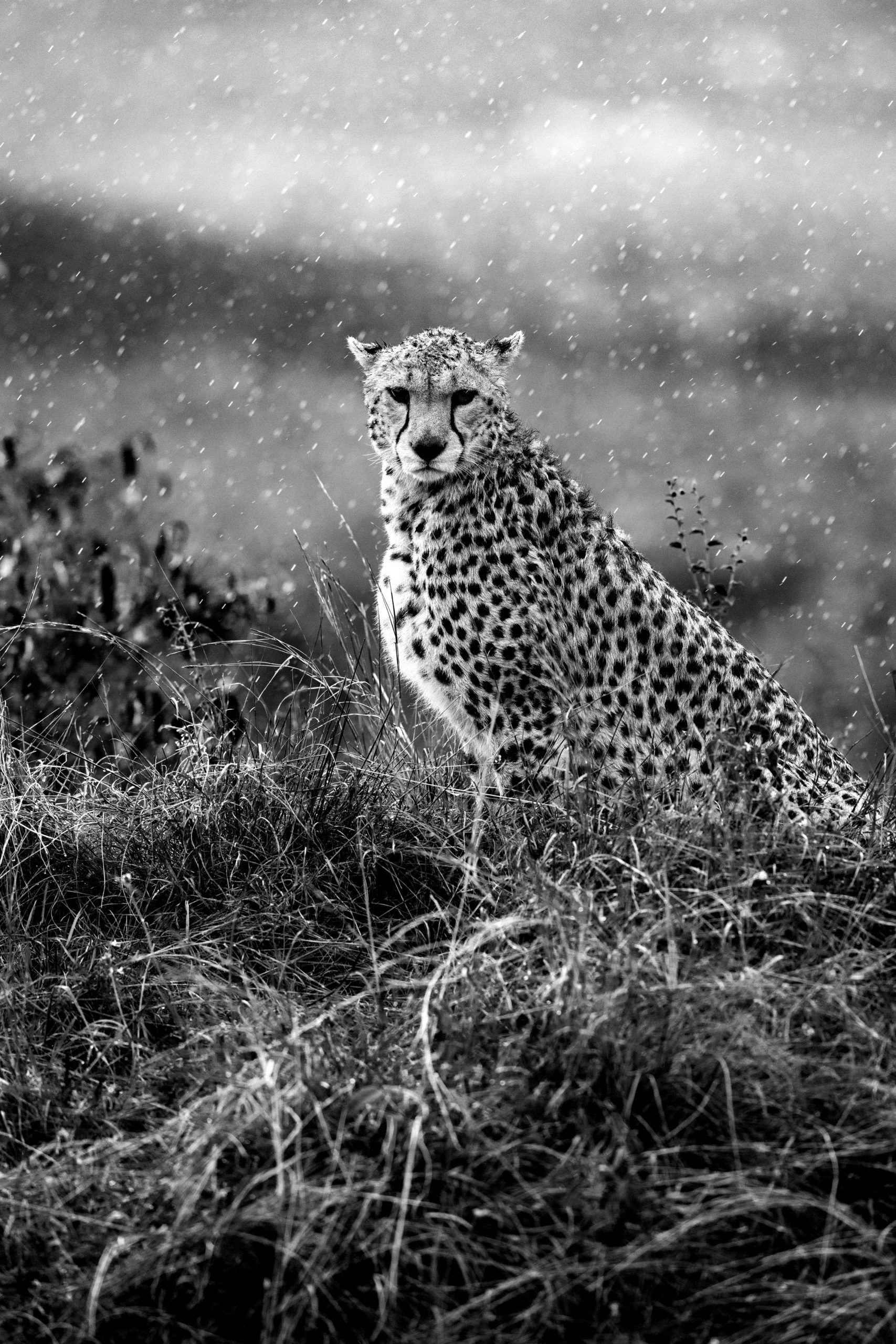

And some days I use a bit of “creative imagination” to manipulate an image to form something beyond what I witnessed. As in the photo above, converting it to black and white transforms a “mere” pretty picture of a cheetah into a portal that connects the viewer with feelings and mood a bit more universal.

In the color version we have a shared viewing experience as we all gaze outward at the beautiful scene. The B&W version may offer a more individual, internal journey and reaction that can have very little to do with a cheetah sitting in a driving rainstorm, on a continent far, far away.

The realistic color version connects us to nature, while the B&W version connects us to ourselves – perhaps reminding us of the storms that we weathered in our lives and how we persevered.

Wow, if I keep rambling like that I will have to get a turtleneck sweater, beret, and start smoking little French cigarettes.

Seems all a bit highfalutin for this small town boy (Art, Schmart). All I can say is, if you find joy, or a shared sense of awe, or brief respite from a troubled day with one of my photos, whether it be Art or something else, then I consider my time well spent.

Until next month….michael

Were you able to remember/guess the original, traditional forms of art? They are:

- Painting

- Sculpture

- Literature

- Architecture

- Cinema

- Music

- Theater

Sources

Is Photography Art? – Both sides of the debate explained.

What are the 7 different forms of Art?

A Brief History of Photography and the Camera

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm f/4 (@f/5.6), 1/1000 sec, ISO 2500

31

Shot of the Month – August 2021

Ok, so first of all, it isn’t that Venice.

And second, the star-crossed lovers are avian in nature, two lovely Great Blue Herons (GBHs), as shown above.

I found this pair of lovebirds at a nesting site (rookery) in the town of Venice, Florida. There is a small lake in Venice with an island of trees where the herons love to build nests and raise their families. It is a surreal to be in such a developed area and then if you turn down one particular quiet street, boom – you suddenly find nesting BGHs, snowy egrets, anhinga, and other assorted wading birds. The alligators in the lake help dissuade any predators (raccoons for example) from approaching the island so the chicks are quite safe in this urban oasis.

lake in Venice with an island of trees where the herons love to build nests and raise their families. It is a surreal to be in such a developed area and then if you turn down one particular quiet street, boom – you suddenly find nesting BGHs, snowy egrets, anhinga, and other assorted wading birds. The alligators in the lake help dissuade any predators (raccoons for example) from approaching the island so the chicks are quite safe in this urban oasis.

Standing up to four feet in height GBHs are the largest herons native to North America and they are one the most successful wading birds in the Western Hemisphere. Their highly adaptive nature allows them to thrive in a range of habitats and they can be found throughout North and Central America, northern South America, the Caribbean Islands, and even in the Galapagos Islands. Great Blue Herons rarely venture far from bodies of water but they can adapt to almost any wetland habitat and may be found in marshes (both fresh and saltwater), mangrove swamps, flooded meadows, lake edges or shorelines.

GBHs feed primarily on small fish but they can adjust their diet to capitalize on what may be found in a given habitat. They can prey on shrimp, crabs, aquatic insects, rodents and other small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and birds. For example in Nova Scotia 98% of their diet is made up of flounder while in Idaho voles make up to 40% of the bird’s diet.

These adaptable birds can even be found in highly developed areas, like Venice, Florida as long as there are bodies of water nearby with a food source.

I visited the Venice Area Audubon Rookery during a December when the birds were just beginning their nesting season. The GBH is normally a solitary bird but they breed in colonies that can include 5 to 500 nests. Males tend to arrive at the rookery first and begin building a nest.

Nest building — It all begins with a stick:

During the mating season the Great Blue Herons perform elaborate courtship displays to attract a mate and to build bonds between partners.

Here we see two males stretching their necks to display the glorious neck plumage that develops during breeding season to demonstrate how attractive they are.

Pick Me No, Pick Me

Once the birds pair up the male flies back and forth bringing nesting materials for the female who completes the nest construction ensuring that everything is just right.

When the male returns to the nest after each sortie the couple will often perform ritualized greetings, stick transfers and a nest relief ceremony where they birds erect their plumes and clap their bill tips together.

Ceremonial Stick Handoff:

Here we have some bond-building bill clapping (say that three times fast…):

If all this fancy courtship goes well you get, ehhhh, an adorable (??!!) bundle of joy as shown below:

Ahhhh, Venice — love is definitely in the air at this birding hotspot. If you dig bird life consider a romantic get away to visit the rookery between December to May for a fascinating view of the courting ways of the Great Blue Heron and their avian brethren.

Until next month…..michael

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), f/10, 1/500 sec, -0.5 EV

Sources:

31

Shot of the Month – July 2021

Check out this month’s crazy landscape — looks like we found a dead tree on planet Mars. This other-worldly scene can actually be found just down the street (as least on a cosmic-size scale) in Wyoming on planet Earth. This dead tree is part of the ever-changing landscape at Mammoth Hot Springs (MHS) in Yellowstone National Park.

How did Mother Nature work her magic this time?

Before reaching the sprawling network of hot springs the water that feeds the site first passes through an underground formation of limestone leaving it rich in calcium carbonate. When the hot water is released into the air it cools quickly and leaves an ever growing hillside of terrestrial limestone (known as Travertine). Each day the cooling water from the springs deposits two tons of new building material creating an ever changing landscape of sculptures, terraces, and new formations. For thousands of years the hillside has grown and changed as the waterflow ebbs and shifts over time.

Ever visited a cave and seen amazing stalactites and stalagmites? Yeah, basically the same process. The process is so similar that the National Park services describes the Mammoth Hot Springs as “a cave turned inside out.”

The dramatic colors are thanks to the range of bacteria that thrive in the warm, wet ecosystems created by the springs. Each type of bacteria has its own color and is uniquely suited to a given temperature range and acidity level. Yellow bacteria indicate very hot water while greens and blues indicate cooler temperatures. Two orange colored bacteria, Phormidium and Oscillatoria can be found in MHS and may be the source of those hues in my image above.

So, if you dig the groovy formations found in caves, but are also claustrophobic, then check out Mammoth Hot Springs for wondrous geology in the comfort of the open air and blue skies.

Until next month….m

The MHS are located near the North Entrance of the park near the town of Gardiner. If you are heading to Yellowstone NP and want to learn more on how to explore the MHS check out these detailed posts from other photographers:

Mammoth Hot Springs/Guide to the Terraces of Yellowstone

Exploring Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone

Sources

Nikon D4S, Sigma 150-600mm (@ 150mm), f/6.3, 1/500 sec, ISO 1600

26

Shot of the Month – June 2021

In 2020 I spent a weekend at Mt. Rainier in search of wildflowers. Ironically, some of the most intense concentration of flowers, and color, can be found along side the roadway. Of course, this is not really the setting for a “wild” nature image that I am looking for. As I was driving from one hiking site to another I saw a Hoary Marmot along the road near a collection of wild flowers. I have seen marmots dining on wild flowers before as you can read about here.

“Oooh, a marmot in those wildflowers? That could be a great shot!”

Luckily there was a car pullout not far away so I slammed on the brakes and pulled over. I walked back along the road to the small “field” and tried to photograph the marmot. From time to time he would stand up and nibble on a flower. As the marmot scampered about I was ducking and dodging trying to

- find a clear shot;

- with lots of color;

- without showing the road nearby;

- without getting hit by a passing car.

The best way to not have the road in the image is to shoot from the road — tricky with cars zooming by. Where is the marmot? Ahh, ok. Click, Click. Take eye from camera view finder and scan the road. Any cars? Yep. Yikes, get off the road.

Ok, now where is the damn marmot? Reposition. Click, click…..Yikes, another car…

This game of hide and seek and dodge-the-car went on for a few stressful minutes. In the end the image above is the only one that kind of worked. The marmot eventually scampered off to flowers down the hillside before I could get THE shot.. The image is a bit of a mess but the photo does offer a nice impressionist sense of the glorious colors that can cover the mountainside for a few weeks each year. With a bit of software I added to the Monet-esque effect:

Mother nature does some of her finest work in the darndest places….

Until next month…..m

Nikon D4S, Sigma 150-600mm (@ 230mm), f/5.3, 1/125 sec, ISO 560