31

Shot of the Month – October 2022

Whoa, that is a BIG bear. Is it a Grizzly Bear? Or perhaps a Brown Bear?

Seems like a simple enough question, but as I have learned over the years, the classification or naming of critters can be a very, very messy affair.

First, let’s start with “What is a Brown Bear?”

The Brown Bear species (Ursus arctos) is the most widely distributed bear across the globe. They can be found in many countries throughout Europe and Central Asia, China, Canada, and the United States. There are approximately 200,000 brown bears in the world; with Russia having the largest population at 120,000 bears. North America is home to about 55,000 brown bears; wherein Western Canada has roughly 25,000 bears, while the United States has about 30,000. Most of the U.S. brown bears live in Alaska (about 98%) with a small population found in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Washington. (source)

Next, “What is a Grizzly Bear?”

Grizzly bears are only found in North America and many feel that they are simply brown bears. Some say that they are a sub-species of Brown Bear. Others say they are a separate clade. Yeah, let’s not go down this rabbit hole or we may lose our minds…

In common usage, meaning not using any fancy Latin words, most folks go with this explanation:

The grizzly bear is a kind of brown bear. Many people in North America use the common name “grizzly bear” to refer to the smaller and lighter-colored bear that occurs in interior areas and the term “brown bear” to refer to the larger and typically darker-colored bear in coastal areas.

Did you catch that terrifying nuance? Grizzly bears, as huge as they are, tend to be the SMALLER version of brown bears. Why is that you may wonder? Brown bears, given the “definition” above, tend to live along the coast and therefore have access to salmon which provide a tremendous calorie boost to their diet, allowing them to grow to massive proportions. Have you heard of the Fat Bear Contest (check out this video)? Yeah, those are Brown Bears, who are all getting fat on salmon. Alaskan Brown Bears, like the female I photographed in Katmai NP above, can eat 80-90 pounds of food/day gaining 3-6 pounds of fat each day in preparation for hibernation.

So grizzly bears are just North American brown bears that are found in forests, interior landscapes, and other places where one cannot dine on salmon. Below is one of those “small” grizzlies that I photographed (read more about that here) in Yellowstone NP a few years ago:

Male grizzlies tend to max out around 400 pounds (females at around 250 pounds) while brown bears can reach double that size. Take all this weight talk with a grain of salt as brown bear/grizzly bear size and weight can vary dramatically depending on location/climate/diet/genetics. The Yellowstone grizzly that killed the elk in the image above, Grizzly 791, is one of the biggest seen in the park and weighs about 600 pounds so he obviously did not get the memo about being smaller.

And where does one find the biggest brown bears? That would be on Kodiak Island in Alaska. The Kodiak bear is a recognized sub-species of brown as they have been isolated from other bears for about 12,000 years – since the last ice age. Those bruisers can reach 1,700 pounds. Yelp.

So if you managed to follow all that, we can say, for the most part, that all grizzly bears are brown bears, but not all brown bears are grizzly bears. And for their size, all we can say is that brown bears and grizzlies are always big. And sometimes really big. And other times, terrifyingly big.

And I didn’t even get into the fact that “Brown” bears are only sometimes brown in color (can vary from almost white to dark tan and everything in between)…..but, my head hurts, so let’s save that for another day.

Until next month….m

Sources

Brown Bear (National Geographic)

Brown Bear (Alaska Fish and Game)

Nikon D5, Nikon 24-120mm (@ 32mm), f/11, 1/350 sec, ISO 360, +0.333 EV

30

Shot of the Month – September 2022

I sat in front of my computer scrolling through thousands of images. Scroll. Scroll…….Which image should I write about this month? Scrolling…..scrolling. The photo above crossed my screen and something about the image caught my eye and I stopped.

This image, taken in Yellowstone in 2014, had been on my computer for 8 years and I had done nothing with it. But I hadn’t deleted it yet so I must have seen something of interest way back then. I enlarged the image to fill my screen.

I stared at the photo pondering, “I like this image, but why?” “What does my subconscious see that I can’t put words to?”

I interrogated myself.

Brain: “What is the subject of this photo?”

Me: “It is a picture of bison.”

Brain: “OK, sure, there are bison in the photo. But, it is not a very good image of bison. The bison in the back is completely out of focus. The bison in the front is in sharp focus but we can’t really see his eye so we can’t make much of a connection which is usually essential for a compelling image.”

Me: Sigh, “True”

Brain: “What else??”

Me: “Well, I see a lot of snow. The bison are framed by snow on the ground. The air is full of heavy snowflakes. In fact, one could argue that the snowflakes are the dominant element in this image.”

And then it hit me. (One could say that the answer came into focus, but that would be a terrible photography pun, and I wouldn’t do such a thing…. 🙂 )

This photo captures not a thing, but reveals a relationship. It tells a story about a struggle. About a fight. Bison face many threats to survival – we mostly hear about the challenges they face from predators like wolves and bears. This image however highlights yet another threat they face, this time, from the very environment they live in. Winters in Yellowstone are long and taxing and many animals do not survive them. In fact. wolves tend to thrive in late winter because prey animals like elk and bison are easier to catch due to their weakened condition.

The elements of this image capture that struggle well. Winter is on the attack – the bison in front had its head lowered as it trods forward, enduring the onslaught. Its body is covered in snow, and the heavy snowflakes obscure much of its being. And the bison in the back is completely blurred while the snowflakes falling around him are in sharp focus. The shift in focus drives home the attack on the lumbering beast. Is he losing the battle and simply fading into oblivion?

The bison counter the offensive by taking refuge in and near the river. Why? The grass they need to eat to survive is buried under deep, heavy snow during much of the winter. However, the snow is less deep right along the banks of the river so the bison forage there, as shown below, as they have to expend less energy to reach the grass. Smart.

While not as dramatic as a cheetah chasing a gazelle, the first image nonetheless captures an epic life-and-death struggle that has played out for millennia. The heart-pounding race between gazelle and cat can be over in seconds. Winter’s attack drags on for days. Weeks. Months. Winter’s pursuit is tireless and unyielding. Freezing temperatures. Howling winds. Whiteout snow storms. Treacherous ice. Tons of snow blocking every move. Day after day after day after day…

For their part, the bison have adapted both their bodies and their behavior to give them the best chance for survival. (Sidenote: Alas, the photographer was not well adapted to these conditions. Nearly a decade later I vividly remember how my frozen hands felt like they were on FIRE after shooting this sequence).

Here is the battle in black and white:

Another view of the combatants, first in color:

And in black and white:

Bison in winter, an Elemental Struggle of the ages.

Until next month……m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/5.6, 1/1000 sec, ISO 1000, EV +1.33

31

Shot of the Month – August 2022

Shhhhhhhhhhhhh……ooh, how delicious. I feel like one of those paparazzi photographers spying on the rich and famous. Peering through the bushes with my high-powered lens to capture an illicit embrace. To get this shot I did lie on my back with my lens resting on my knees – it was the only way to shoot through that small opening in the branches and leaves.

What we actually have here is two lovely Cedar Waxwings performing a courtship ritual known as “courtship feeding.” Usually, it goes down like this:

The male goes off and finds a suitable gift – this could be a piece of fruit, an insect, or even just a flower petal.

He flies over to the female and lands on the same branch. He hops, hops, hops his way over next to her.

He offers the gift. If she digs the guy she will accept it. Now she hops, hops, hops down the branch away from the male.

She then hops, hops, hops back over to him. She offers the gift back to the male. He takes it.

And now repeat, many times. Eventually, the female eats the gift.

The male will go off and find another worthwhile gift and the courtship continues. And if all goes well…..well, you know. Baby waxwings…

Below, this time in black and white, we have the same pair handing off another gift:

On a different occasion, I found two waxwings in a similar pose. The birds were highly backlit so it became this silhouette:

Remember this childhood taunt?

Jack and Jill

Sitting in a tree

K-I-S-S-I-N-G!

First comes love

Then comes marriage

Then comes baby

In a baby carriage!

I am starting to get an idea of where that came from…

Ahhh, courtship feeding – a time-tested strategy shared by bros and birds alike.

Until next month…..m

Check out these videos if you want to see some courtship feeding in action:

And here is a previous post I did on Cedar Waxwings.

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 3200, +0.333 EV

31

Shot of the Month – July 2022

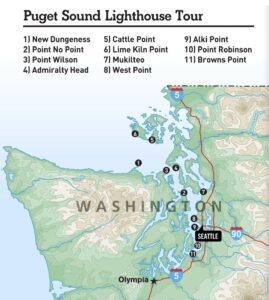

The Lime Kiln Lighthouse, shown above, is located on the western side of San Juan Island and is in just the right spot to accentuate a sunset image (#6 on the map below). The lighthouse was built in 1919 and still serves as a navigational beacon to those sailing in the Haro Strait. This location is also known as one of the best places in the world to view whales from land. Orca whales can often be seen swimming by from May to September each year. From this lovely spot, one can also see Minke whales, porpoises, seals, sea lions, otters, and bald eagles.

I arrived at the lighthouse a good hour before sunset to get the lay of the land and try and explore potential compositions. The water was unusually calm and as the sun slowly set I had an amazingly peaceful hour sitting on the rocks listening to the gentle sound of the water caressing the shoreline. Ahhhh….seaside serenity at its best.

As the sun slipped below the horizon the scattered clouds began to explode with color.

The clock had started — Time to MOVE!

Non-photographers may not realize that one does not simply walk up to such a scene, raise the camera, snap a few shots, and go home. No, usually there is an absolute frenzy of activity behind the camera that beguiles the serenity before the lens.

In my case, I was running from one outcropping of rocks to another and frantically adjusting my tripod to find JUST the right position and composition. This tripod leg up a bit. This leg, down a bit. That leg has to go over there. Nope, this leg is now too low. Raise again. Now the horizon is crooked. Adjust the camera. And all that is even before figuring out the proper exposure settings. Once the camera is in the right position I then run through a range of different shutter speeds and apertures to find the best combination that can expose the bright sky while trying to keep the exposure on the building from going too dark. For this image, I also took a series of shots at different exposure levels that I merged later with software to capture the full range of brightness in the scene. For more on how that is done, check out this post I did on photographing a lighthouse in Maine.

Ok, got that particular shot? Now rush over to a different outcropping and do it all again.

With each moment the light is changing and the colors may be getting better, or worse. With each second that is passing, I am scrambling to maximize what the scene is offering in THAT moment.

This race with the light may last mere seconds, or can go on for 45 minutes. The pressure/stress can be intense to seize the fleeting moment before it is gone.

Either way, by the end, I am usually exhausted.

But so much fun!!

Is the running around worth it? Sometimes yes, (usually yes), sometimes not.

On this outing, I captured several scenes that I really liked. In the above image, we have a classic seascape that oozes serenity and calmness. It is like a visual sigh for the soul.

But in the image below, I found a completely different story and feeling:

By moving closer, I still captured a seascape with a dramatic sky, but now I found a more intimate scene as the couple on the right becomes more prominent in the scene and turns this into a love story. The upper image will most likely have the viewer looking outward to the world while the second image will nudge the viewer’s mind inward as s/he remembers a similar sunset embrace.

Photography is about storytelling and by continuing to move around the scene I was able to find two lovely, but very different, stories. On this night, I was able to go from Landscape to Lovers in just a few feet.

Until next month…….

Nikon D850, Nikon 24-120mm (@24 mm), f/10, 1.0 sec, 7 shot Bracket (HDR merge)

30

Shot of the Month – June 2022

The natural world is filled with stunning beauty. I am certainly drawn to it and spend much of my free time trying to capture it with my camera. However, surviving in the wild is not for the faint of heart as life in the food chain is an endless battle between predator and prey. Many of us are attracted to the predator as we admire their cunning and specialized skills. Others root for the prey, especially if said prey is cute and cuddly.

In this post, I will share images where the predator was successful. This post will not be for everyone – if you are squeamish and don’t like to witness this harsh reality, I suggest you skip this month’s images.

In 2021 I went on a safari to Kenya that was focused specifically on the big cats. We would spend hours searching for lions, leopards, or cheetahs with hopes of witnessing those epic life-and-death struggles. The trip was so “successful” on that front that by the end we were quite traumatized by the amount of death we witnessed. We definitely experienced PTSD – Post Traumatic Safari Disorder. During a 10-day period, we saw a life-and-death struggle almost every day and sometimes several times a day.

Cheetah Mother and Cubs

We spent many hours over several days with this cheetah mother and her three cubs. The female was absolutely stunning looking and was by far the most impressive cheetah I have ever seen. Cheetahs are often timid and skittish. Not this female. She was powerfully built and walked with a confidence and swagger, unlike anything I have ever seen with a cheetah. Every day she had to find a meal for her growing cubs and we saw her hunt several times. In the image above mom caught a young impala but she did not kill it. Rather, she called her cubs over to have them learn/practice how to suffocate their prey. It was a tough scene to watch as the cubs didn’t know how to effectively apply the neck bite and the death was slow and drawn out. While it was a sad end for the impala, the cheetah mom had again provided essential food for her family and taught her cubs important life skills that they will need if they are going to survive on their own.

Piglets

One morning we drove to a location where we heard that two cheetahs had been spotted. As we approached we saw a couple of other vehicles sitting nearby. We had no idea where the cats were but we surmised that the cats must be sitting or lying in the tall grass in front of us. We stopped the vehicle and prepared ourselves for a long wait. But only five minutes later…

“Holy Crap!!” A warthog mom and her two piglets appeared out of nowhere and trotted down the path towards us not realizing the danger that lurked nearby.

After a brief stop, the warthog family continued down the road. The two cheetahs exploded from the grass. Mom warthog bolted straight ahead while the piglets ran in the opposite direction. The two cheetahs began chasing Mom but after a few yards, they stopped. The cats realized that the easier meal was behind them. The cheetahs changed direction and moments later each had caught a piglet.

In the blink of an eye, the mother warthog lost her entire family. In this image, we see the two cheetahs fighting over one of the piglets:

Young Topi and Young Lion

Near the end of a long day, we found a pride of lions stalking a herd of Topi that was about 100 yards in front of our vehicle, a bit off to the right.

While waiting I looked behind our vehicle and saw an adult Topi that seemed to be bleeding. I looked through the binoculars and saw blood on her rump. I said, “Hey look, that adult must have been attacked by a lion but managed to escape with those fresh wounds.” My partner took the binoculars and said, “No, she just gave birth, the newborn is lying just nearby. That blood is the afterbirth.” What a wonderful surprise.

Our joy was short-lived.

In the next moment, a young lion cub appeared and ran over and grabbed the newborn calf – most likely his first kill as a very young lion. The young calf’s “circle of life” was complete in just a few minutes and this emotional roller coaster left us reeling as we careened from joy to horror in seconds.

It was quite dark when I shot this image so the shutter speed was quite slow – the motion blur helps soften this Shakespearean tragedy – a bit. This was a particularly traumatic day – our day started with the warthog piglets and ended with the topi calf.

But the day had one last surprise. While watching the young lion run off with the topi calf we heard a commotion back out in front of our vehicle. We drove over and found that the stalking lion had just captured an adult topi.

A very tough day for the topi herd.

But don’t let these selected stories mislead you – we saw multiple other encounters where the prey won the day. Life is a struggle for all wildlife, predator and prey alike. In reality, the vast majority of predator hunts end in failure. Likewise, most young lions, leopards, and cheetah cubs never make it to adulthood.

I admire the beauty in both sides of the struggle. And I take solace that with each life lost, the “sacrifice” allows others to survive and keep the ecosystem in balance.

Ok, I promise, next month, definitely something cute and cuddly…

Cheetah Mom with Cubs (Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm, f/5, 1/4000s, ISO 720

31

Shot of the Month – May 2022

This month I share an image of a lovely Black-shouldered Kite (BSK). I photographed this beauty during a downpour in Masai Mara NP in Kenya (if you look closely you can see the rain coming down). The BSK gets its name from the dark shoulder patches on its wings and it is the contrast of those dark wings against the white underbelly that first caught my eye. But as I looked more closely at this bird hunkered down in the rain, I noticed that the head and back are draped in exquisitely blended gradients of gray. To add a bit more flair the BSK has striking yellow feet, a yellow beak, and dramatic red eyes.

Yes, I am smitten with this little raptor.

So let’s get our terminology in order. A bird of prey is called a raptor. A raptor is a bird that mainly uses its claws (talons) to seize prey. But what makes a Kite a Kite?

For you science types, Kites are birds found in three subfamilies (Milvinae, Elaninae, and Perninae) of the family Accipitridae. There are about 25 species of Kites found around the world. Y-e-e-e-aaaah, that’s not super helpful – got anything else?

Here’s what I could find:

- Kites, as a group tend to have weak legs so they like to spend most of their time in the air. In flight, kites often flap their wings once and glide for long distances before flapping their wings again. While gliding, the wings are tucked behind the bird to create minimal air resistance so the bird seems to float through the air.

- Kites typically have long, narrow wings and tails.

- Kites often have forked tails. (The BSK has a square tail, so there are exceptions)

- Kites have small heads and short beaks. The face of many kites is partly bare as many of them feed on carrion and the bare flesh makes cleanup easier.

The BSK prefers open land and semi-deserts in Sub-Saharan Africa and tropical Asia, and for some reason, they can also be found in Spain and Portugal.

This small raptor tends to dine on rodents, grasshoppers, crickets, lizards, and sometimes on injured birds, small snakes, and frogs. The BSK is about 12-15 inches (30-36 cm) in length, with a 30-36 inch (76-91 cm) wingspan, and only weighs about 7-12 ounces (200-350 grams).

When hunting the BSK sometimes hovers over a field looking for prey (similar to what kingfishers do over water). Other times the bird will fly slowly, close to the ground in search of a meal. And yet other times the BSK will sit on a perch scanning the ground for prey – once spotted the bird will dive down to scoop up the unsuspecting victim.

As for the photo, as mentioned earlier, I love the look of this gorgeous raptor. I shot with a wide-open aperture to cause the background to disappear into a quiet blur and allow the bird to really pop out of the image.

In the image above I zoomed in to create a nice portrait of just one BSK. Actually, there were three birds sitting on a dead tree as they waited out the rain together (our portrait guy is on the right):

The two birds on the left are flapping their wings to shake the rain off.

While in Kenya we spent most of our time focused on finding the big cats – lions, leopards, and cheetah. And boy oh boy, we found a bunch of them. We had amazing sightings of said cats every day. And despite all that I have to say that sitting with this wee raptor, as the rain gently plopped, plopped, plopped on the canvas roof of our land cruiser, is still one of my favorite memories from the entire trip. I had never seen a BSK up close before (via my powerful lens) and it was a wonderful revelation.

Until next month….michael

Here is a fun video of a Black-shouldered Kite hovering (watch how the head barely moves!)

Sources:

All Things Nature (What is the Bird called a Kite?)

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 1100, EV +1.0

30

Shot of the Month – April 2022

While living in Vermont I spent many a summer weekend morning in my kayak searching for Atlantic Loons. This meant getting out of bed very early and driving for 1 to 2 hours in the dark to one of several nearby lakes to ensure that my kayak hit the water before sunrise. If it all worked out well I would be able to photograph the loons in the golden light just after sunrise. Occasionally, it all came together:

Click here for the backstory on the image above.

One day I reached the lake early and began paddling out into the fog to look for loons. As the rising sun started to burn off the fog I could finally make out a loon in the distance. I saw that the bird was swimming to the farthest bank.

Oh no!!

I knew that this meant that he was planning to fly off to another lake. He was “taxiing” to the far bank to get enough space for take off. Loons are heavy birds and need a long “runway” to build up the speed for flight. Check out my post Looner Flight – No Small Feat for more on the wonders of the Atlantic Loon (aka Common Loon).

I started paddling furiously. I was looking directly into the sun and I wanted to get to the other side of the loon before he took off so I could photograph him with the sun behind me so the bird would be front-lit.

Too late!

The loon started to flap his wings and began his sprint. I put my paddle down, grabbed my camera, and held down the shutter button.

With the sun behind my subject, I wasn’t able to capture the rich colors I hoped for but the striking image below is an example of the magic that can happen when the subject is backlit. In this case, the sun was behind the loon and produced wonderful highlights in the water as the bird skipped across the surface. I love how his one foot is just kissing the surface of the water.

Backlighting allows us to highlight the shape of an animal or explore dramatic light and shadows in a scene. The lighting in the image below allows us to easily make out a moose walking along a ridge line in the Grand Teton NP.

In the next image, the backlit grass seems to radiate from within. The dust adds drama and highlights the form of the bison (Grand Teton NP).

Backlighting can create a dramatic rim light on an animal and highlight their fur or feathers as we can see with the moose below. The backlit plants in this image also add drama to the scene. On this cold morning, the moose’s breath is also backlit. (Grand Teton NP)

Leaves are a natural candidate for backlighting. Here we have a cathedral of color from these backlit Vermont trees:

Getting the exposure correct on a backlit subject can be tricky so you will definitely need to experiment with your settings to create the effect you are striving for. Despite the challenges, shooting into the light, with the sun behind your subject, is a great way to create dramatic images that stand out from the crowd and capture the beauty of nature in a, uh, well, different light.

Until next month…..michael

Here are some good articles on tackling backlighting:

Backlighting in Wildlife Photography: Creative Use of Light

Master backlighting with your wildlife images

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm f/4, 1/8000 sec, ISO 640, EV -0.5

31

Shot of the Month – March 2022

Travel to the high desert of Eastern Oregon and you can gaze in wonder at the Painted Hills as shown in the image above. These mellow, albeit colorful hills are a time capsule of a tumultuous past that is hard to fathom. Believe it or not, this place was once a tropical forest that was thick with vegetation, palm trees, bananas, and avocados. The area would get 80 inches of rain per year — this desert now only receives about 15 inches of moisture a year, mostly in the form of snow.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let’s start at the beginning — waaaay back. This epic tale began 35 million years ago when massive volcano eruptions in the Cascade Mountains, a hundred miles to the west, blanketed this area with ash and pumice. Over time the ash and sediments were mixed by natural processes including the flow of water, growth of plants, and the movement of animals. The surface ash was oxidized over the passing eons. Buried under new layers and deposits, the ash turned into soils by way of compaction and cementation. With more time and weathering, the exterior surfaces of The Painted Hills were worn into clay. Now, they are primarily made of hard claystone layers.

Over the millions of years since those first eruptions, the area has experienced wild shifts in climate. Millions of years ago this space was home to weather more like Costa Rica – the tropical forests I mentioned earlier. Over time the climate shifted again and the area became a grassland with oak and maple trees. Those stunning colorful red, yellow, and black stratifications in the hills above are a signpost of each different climate reality.

The red stripes are laterite soil that was formed by floodplain deposits when the area was warm and humid. The darker black soil is lignite which was vegetative matter that grew along the floodplain. The yellow soils were formed during dryer, cooler climates. With each new climate, the landscape dramatically changed bringing different types of vegetation, water levels, temperatures, and animal life. Areas near the Painted Hills are rich with fossils from plants and animals – one can find fossils of saber-toothed cats, early horses, camels, and rhinoceroses to name just a few.

Standing on this quiet overlook, it is hard to comprehend the scale and breadth of the cataclysmic changes this land has seen.

These hills strike me as a powerful reminder that when we meet a hill, or a person, what we see today does not tell their entire story – they may have had a past, and may have a future, that is wildly different from today’s snapshot. Likewise, we can only imagine what they may have endured, for better or worse, to reach their current state.

Until next month…

Sources

If you want to photograph the Painted Hills here are a few good guides:

Here is a great overview on visiting the Painted Hills: Painted Hills of Oregon: Everything You Need To Know

Another guide: Exploring Painted Hills, Oregon

Another good guide: A Stunning Guide to Oregon’s Painted Hills

Nikon D850, Nikon 24-120mm (@35mm), f/8, 1/90 sec, ISO 64

28

Shot of the Month – February 2022

If you have any nature photographer friends you may have heard them talk wistfully about the “Golden Hour.” It is that special time of day just after sunrise or just before sunset when the light takes on magical hues of red, orange, or yellow and has a certain softness that seems to gently caress whatever it falls upon. During “Magic Hour” the sun is low in the sky, only a few degrees from the horizon.

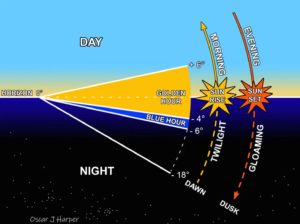

The lesser-known cousin of Golden Hour is Blue Hour. I kid you not – it really is a thing. To explain it I have to get a bit astronomical-like, so strap in. And, uh, bring along your protractor…

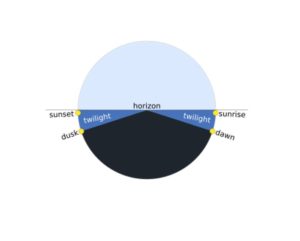

At its simplest, Blue Hour takes place during twilight. I have heard this term my whole life but what exactly does it mean??

Twilight is the time between day and night when there is light outside, but the sun is below the horizon. During this period the light we see does not come directly from the sun but rather is scattered and refracted from the upper atmosphere down to our eyes.

Now for the more complicated version. Time to break out those protractors (And see, you thought that box in your attic from 3rd grade wouldn’t come in handy. Tsk. Tsk.)

Astronomers were not satisfied with just one “twilight” and created a more precise delineation as shown here:

Let’s break it down.

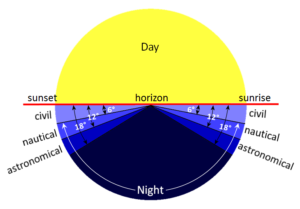

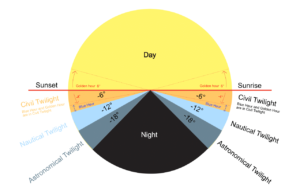

Astronomical Twilight: The sun is located 12 to 18 degrees below the horizon. In astronomical twilight, sky illumination is so faint that most casual observers would regard the sky as fully dark, especially under urban or suburban light pollution. During astronomical twilight, the horizon is not discernible, and moderately faint stars or planets can be observed with the naked eye under a non-light-polluted sky. In the evening, when the sun is at 18 degrees below the horizon we have Dusk, the end of twilight, and the beginning of full evening darkness. In the morning, when the sun is 18 degrees below the horizon, we have Dawn, marking the end of full darkness as we begin the morning twilight.

Nautical Twilight: The sun is 6 to 12 degrees below the horizon. In general, the term nautical twilight refers to sailors being able to take reliable readings via well-known stars because the horizon is still visible, even under moonless conditions.

Civil Twilight: The sun is located less than 6 degrees below the horizon. Civil twilight is the period when enough natural light remains that artificial light is not (usually) needed.

Still with me? You are probably thinking – “Ok Galileo, this is all mildly (barely) interesting, but where the heck does Blue Hour fit in all this?”

Here ya go:

Blue Hour takes place when the sun is between 4 to 6 degrees below the horizon which is usually about 30-40 minutes after sunset/before sunrise. During this period the light takes on deep shades of blue and can produce unique images. Truth be told the Blue Hour really only lasts about 20 minutes but the duration varies by where you are on the planet.

I like this graphic also (some may find this one clearer):

(Did you notice “Gloaming” in the graphic above? It is just an Old English/Scottish term for twilight)

So that was a lot of blah blah to talk about the Blue Hour — more importantly, here is some of the magic it can work:

In this image we have a herd of giraffes strolling by shortly after the sun has set on the Serengeti plains of Africa (Masia Mara National Reserve in Kenya, to be precise).

Here is what the scene looked like while the sun was still above the horizon (late golden hour):

So, if you want to get your blue on you have to get out there waay early or stick around waay late, and then you have to work fast because blue time flies especially fast.

Now, don’t be blue, but we have reached the twilight of this post.

Until next month…..michael

Sources:

Mr. Reid.org (dawn-dusk-sunrise-sunset-and twilight)

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm, f/4, 1/400 sec, ISO 2000, -0.5 EV

31

Shot of the Month – January 2022

Many photographers love to “fill the frame” when they photograph wildlife. Many spend a tremendous amount of time, energy, and money to have the skills, equipment, and opportunities (photo tours) to allow them to get close to wildlife and capture an image that is filled from top-to-bottom, side-to-side with that fuzzy/furry/scaly natural wonder. Photographers will spend thousands of dollars for the largest lenses to give them the extra reach to magnify their subject.

Yep, all sounds pretty familiar – you can lock me up for this also – guilty as charged.

Our offense is understandable – we love wildlife and such images allow us to see details that one can rarely see with the naked eye. Such close-ups allow us to revel in the beauty of our subjects.

The downside is that you can go online and find thousands, and then many more thousands of images that look more or less the same.

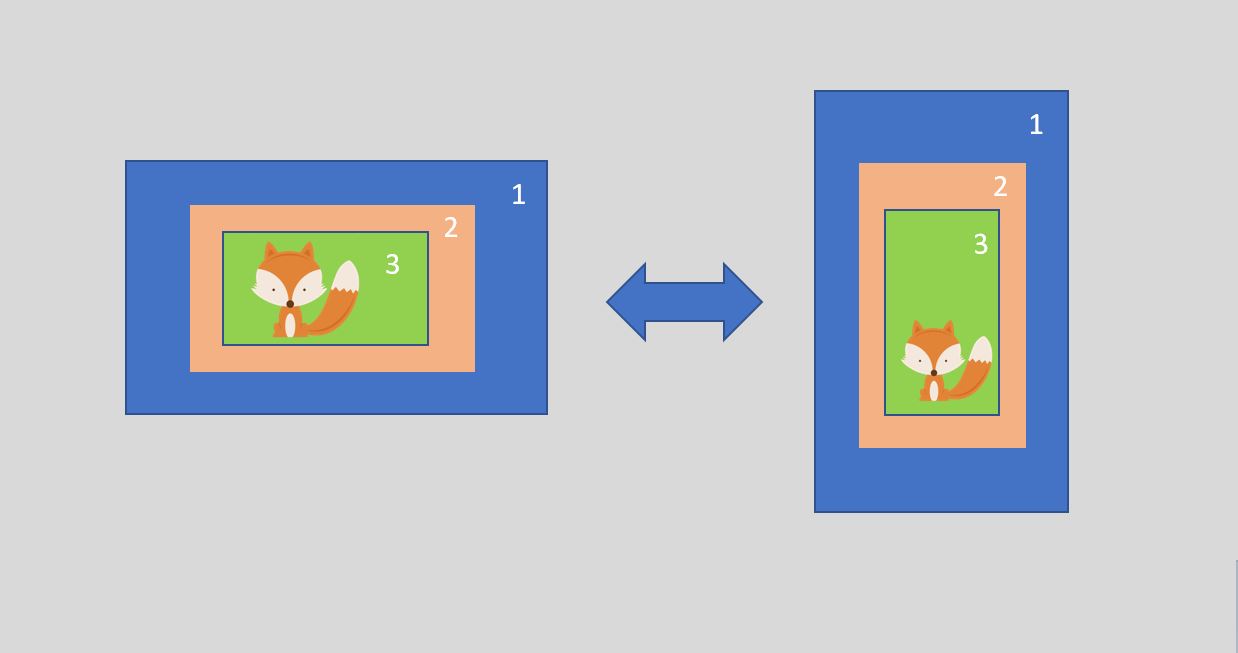

To avoid this common mistake and get beyond the simple “animal portrait” when shooting I push myself to try and get at least 3 shots with different levels of zoom on the subject. And if I have even more time I rotate the camera 90 degrees and take another 3 shots with different levels of magnification. This can be achieved by either moving yourself (those boots were meant for walkin) or by using a zoom lens that can change focal length.

By pulling back I can place the animal in its environment or habitat and tell a more complete story about its life. For example, in the image above I purposely did not zoom in to allow the viewer to see this brutal, albeit beautiful, winter landscape, because it is as important to the story as is the moose. The wider view gives a sense of what life is like for a moose in the winter in the Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) in Wyoming.

Looking at that scene I can’t help but get a shiver down my spine.

Here is another one of my favorite images – by pulling back we see not only a magnificent bull moose but we also get to revel in the colorful bounty of fall in the GTNP.

I rarely share images of moose without antlers (cows, young males, post-rut males) as they usually are not as photographically interesting. In the image below however, the landscape adds so much to the story it becomes a keeper.

So, don’t get me wrong, I love me a great close-up portrait. My point is ok, once you get that shot, now keep going and explore what other stories can be told. The “environmental portrait” is a wonderful way to broaden and deepen the story and connect the viewer to not only the animal but also to the place they call home.

Until next month….m

Nikon D5, Nikon 70-200 mm f/2.8 (@105 mm), f/5.6, 1/180 sec, ISO 140, EV +1.0