31

Shot of the Month – August 2023

This month a lovely fox kit bathed in glorious afternoon light. Foxes are always cute but the warm glow in this shot really takes the image to the next level.

We found this den on the edge of a federal park in Washington State. In previous years visitors could enter the park and observe the dens at a distance of 75 feet or more. Access to the park has been restricted in the last couple of years. Ironically that lack of humans near the dens seems to have emboldened bald eagles who reportedly killed most of the fox kits last year before they could reach adulthood.

During my visit I saw a bald eagle swoop in twice to try and steal a rabbit carcass that an adult fox had just given its kit. Luckily the young foxes were big enough at this time of year to be less at risk for predation by the raptor.

In the two images below I managed to capture one of the attacks by the bald eagle. The fox kit had seen the approaching raptor and was running for the entrance to the den with the carcass.

Run!!!

So close!!

The kit managed to duck underground just in time. When the parents were present they were always diligent and would bravely leap up at the bald eagle as it approached.

It is interesting to consider that the foxes may have established their den near the dirt road on the edge of the park to use the nearby humans to discourage the eagle attacks.

Red foxes mate in the winter and the pups are born 7-8 weeks later. Both parents take care of the kits and each go off hunting to bring back food for the young. Foxes raise their pups in a den which has been abandoned by another animal – in this case it was most likely a former rabbit den. Amazingly, there were rabbits in holes just a few feet from the foxes’ den! Talk about keeping your enemy close!

The cubs remain at the family den for about 5 weeks before going off on their own near the end of the summer.

The kits spend most of their time underground when the parents are not present though as the pups get older they will explore the surrounding areas more and more on their own. In my image above I captured the young fox out exploring his world while he waited for his parents to return.

Like foxes? Check out these posts for more images and fox tales…

Until next month….m

Nikon D5, Sigma 150-600 mm Contemporary (@480mm), 1/1000 sec, f/8, ISO 1250

31

Shot of the Month – July 2023

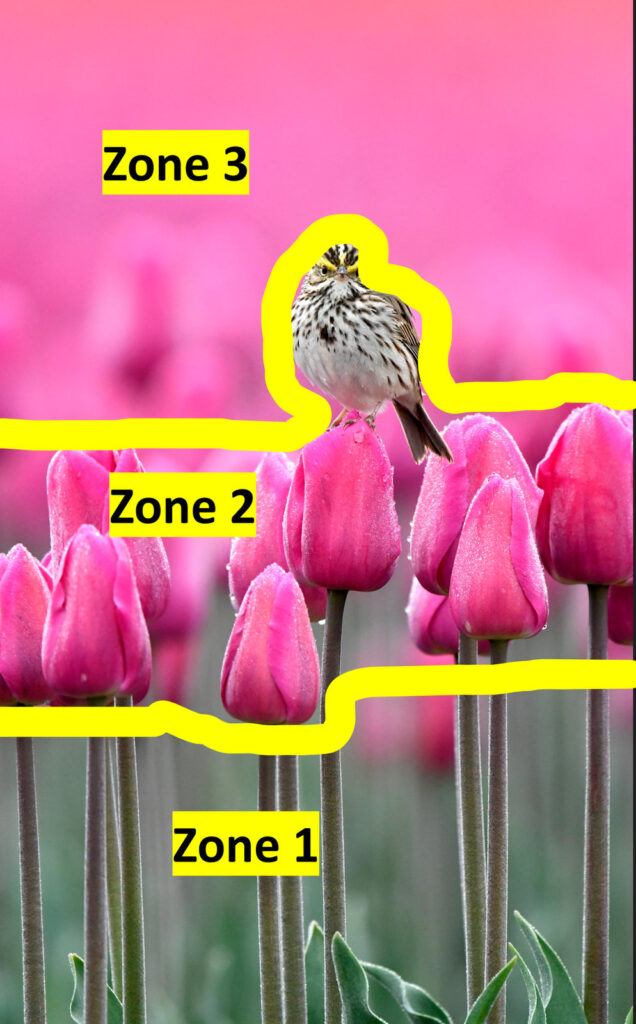

This month a fun blast of color from the tulip fields of Skagit County in Washington State. In this image I found a Savannah Sparrow guarding this fuchsia-colored field of tulips.

I shot this photo in portrait orientation as those long tulip stems were best highlighted and celebrated with a vertical composition. I also really enjoyed the different “zones” of this shot:

Zone 1: While the stems are in sharp focus (you can see the t-i-n-y hairs on the stems!) the background fades away into a pleasing out-of- focus green and your gaze can go on forever…

Zone 2: In this zone we have a dramatic shift in color and at this distance all of the flowers are in sharp focus. Likewise, our lovely Savannah Sparrow is nicely crisp as he poses for his portrait.

Zone 3: In zone 3 another dramatic shift in focus as the tulips vanish into a deep blur but the bold fuchsia hue still demands attention. The Savanah Sparrow really pops against that blurry background.

Another view from the Fuchsia Field:

Check out this post for more on my adventures photographing Savannah Sparrows among the tulip fields.

Until next month….m

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm w/ 1.4x TC (1275mm effective), f/5.6, 1/640 sec, ISO 2500, +1.0 EV

30

Shot of the Month – June 2023

I spent the better part of a week in May, staked out along a dirt road, in a national park where I could observe a fox den. Each day, while dutifully wating for canine action, we were visited by this dandy chap and his mate. In this beautiful afternoon light we can see the male California Quail (CQ) in all his glory.

I love some of the descriptions that I found while researching this beautiful bird:

These plump, chicken-like birds are easily recognized as quail by their overall jizz and plump body shape

and

The California Quail is a handsome, round soccer ball of a bird with a rich gray breast, intricately scaled underparts, and a curious, forward-drooping head plume

While the whole “round soccer ball of a bird” thing is a bit rude, ummm, well….

I can’t say it is wroooong….

Another fun description:

The California Quail is distinguished from other quail species by its unique plumage pattern and the presence of a forward facing comma-shaped black plume that makes them look like a flapper from the 1920’s.

I had been racking my brain trying to find the right words to describe that wonderful plume and this person nailed it : “a forward facing comma-shaped black plume…” It does look like a comma!!

Insider Tip: Although the plume looks like one feather it is actually made up of 6 overlapping feathers.

The females also have a plume though to my eye it is more “exclamation-point-esque” and lacks the flair of the full comma!

CQ are most active near sunrise and sunrise and that certainly was our experience with these birds. Each morning and late afternoon this mating pair would come wondering down the road like clockwork. CQ spend most of their time on the ground but they will take flight to avoid predators.

The CQ is a granivorous bird that eats mainly grain and seeds, and weeds like dandelions. In the summer they also catch insects to provide additional protein for their young. These birds are rather chicken-like as they prefer to scratch 2-3 times on the ground with one foot before pecking at the ground to grab the seeds or insects they scared up.

The “lovebirds” afternoon stroll:

Peck peck peck…

Here the male is calling loudly, claiming his territory. And obviously showing off for his mate…I love the foot in the air for extra effort.

Did you notice the dashing yellow and chestnut coloration on his stomach?

California Quails can be found in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Nevad, Utah, and of course, California. CQs have also been introduced into Hawaii, New Zealand, Chile, and Argentia.

Fun fact: The CQ is the official state bird of California and is the only state bird whose name includes the full name of its state. (A bit of ammo for your next dinner party as the conversation wanes….)

There you have it, the California Quail – a striking dandy of a bird that prefers hoofing it over flight, but does so with style and panache.

Until next month….m

Sources:

All About Birds – California Quail

Kids National Geographic – California Quail

Nikon D5, Sigma 150-600mm (@ 600mm), f/6.3, 1/1000 ISO 800

31

Shot of the Month – May 2023

Brace yourself, Sheila…. (scroll down veery slowly….and best viewed on a large screen)

Ok, I still wasn’t ready. Wow.

For the uninitiated, that is an extreme close-up of a Southern Ground Hornbill (SGH). I photographed this fellow in Kenya. To be fair, how many of us would pass the extreme close-up test??

(If you are viewing on small screen you will definitely want to zoom in to really appreciate the full effect)

The SGH is one of my FAVORITE creatures on the planet. Every sighting of these birds is an absolute delight.

Lets run through what makes them so special:

Killer Looks

There is no denying that these birds are striking in their appearance. The SGH is a large bird (wild turkey size for quick comparison) that can stand 4 feet tall (1.2 m), weigh up to 15 pounds (6.8 kg) and he definitely draws attention with his dramatic markings. The male’s face and throat is adorned in bright red and he can inflate that neck wattle to attract the females. The female looks similar though her neck wattle will have a violet blue patch for easy identification.

And did you notice those sumptuous eyelashes? Those are actually modified feathers!! They are used to protect the bird’s eyes from dust and sunlight.

Of course the other key defining feature of the SGH is that massive, slightly curved hornbill. It is an effective tool for foraging and capturing prey.

A good view of the SGH’s hornbill:

Just a stunning looking creature!

Amazing Sound

The males can use that large wattle to create a booming call that can be so loud that it can be mistaken for a lion’s roar and can be heard almost 2 miles (3 km) away. The large bump on the bird’s bill is a chamber that is used to amplify their calls. He basically has a built in boom box.

Click on this video to hear a small sample of one of their wonderful calls (Link here):

(Did you notice the lovely blue patch on the female on the left?)

Chill Vibe

SGHs live in groups of 2-12 individuals led by a dominant mating pair. The group spends most of their day walking slowly in search of food. These guys are just so cool and ganster as they come strolling by on the savannah. SGHs can fly and they roost in trees at night but they prefer sauntering and can cover up to 7 miles/day. (11 km/day).

These birds are carnivorous and will eat just about anything they can catch and fit down their throat. Prey include insects, frogs, toads, lizards, snakes and tortoises. SGHs will also hunt hares, rats, squirrels and even small monkeys. Once in Botswana I saw a crew come through a field and they were just destroying the small wildlife. Peck, there goes a spider. A few steps later, BAM, caught a lizard. A few more steps, POOF, caught a grasshopper…..they were relentless.

Many years ago I witnessed an epic battle between a SGH and a frog. You can read about it here.

A SGH tossing back a spider snack

Fascinating Family Life

Scientist describe the SGH as an “obligate cooperative breeder.” Scientists really know how to suck the romance out of something. So what does that mean??

A SGH family group is made up of a dominant male and female while the rest of the group members are typically younger males from previous clutches. The “helpers” support the mating pair in raising the chicks and will hunt, help take care of the young, and do much of the “work” of the flock. Female offspring may stay with the parents for only a few years as only one adult female is tolerated in a group and breeding is strictly between the breeding pair.

Experiments in captivity indicate that birds without at least 6 years experience as assistants rarely breed successfully if they do become breeders!! And studies show that if assistants are not present, adult SGH often fail to breed successfully.

At Risk

Sadly the SGH is struggling to survive and the species is listed as vulnerable to extinction globally. In South Africa, Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland the bird is listed as endangered. The bird is also found in Angola, Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It is estimated that only 3,000 birds remain in the wild and numbers are dropping in most countries.

The primary threat to the SGH is loss and fragmentation of habitat as humans expand their footprint into wild areas. Hunting and poisoning of SGHs is a growing problem.

Another key issue is that the SGH is one of the slowest reproducing birds in the world. The SGH has an unusually long life span – up to 50 years in the wild and up to 70 years in captivity. However, these birds often do not reach sexual maturity until 4-6 years old and may not start breeding until 10 years old.

Although the female usually lays more than one egg, only one chick will survive more than a few days. The parents will ignore the younger siblings even when food is abundant. Scientists hypothesise that the other eggs are “insurance” in case the first egg does not hatch.

This lone chick matures slowly and is dependent on the parents for at least 2 years. Put this all together and a SGH group typically only produces and raises one new offspring every three years. This makes it difficult for the SGH to increase population numbers while under growing threats.

Somewhat encouragingly there are a wide range of conservation efforts now underway in many countries. Some groups focus on growing support to stop hunting and persecution of the birds. In other places scientists are collecting the 2nd chick from the nest before it dies. The scientists raise the chick and then reintroduce it into the wild.

Fingers crossed that we will have these wonderful, charismatic birds galavanting across the savannah for many generations to come….

Until next month….m

Sources

Africa Geographic – Southern Ground-Hornbill

Worldland Trust – Southern Ground Hornbill

Africafreak – Southern ground hornbill facts – Lifespan, habitat & diet

National Geographic – Southern Hornbill

Wikipedia – Southern Ground Hornbill

Nikon D5, 600mm f/5.6, 1/1500 sec, ISO 2000,

30

Shot of the Month – April 2023

The Pacific Northwest (PNW) is chock full of “must-see” natural wonders and unique landscapes. A few that I have seen so far:

Mount Rainer and the nearby Reflection Lake

Peter Iredale Shipwreck (Sunset) (Visit at Sunrise)

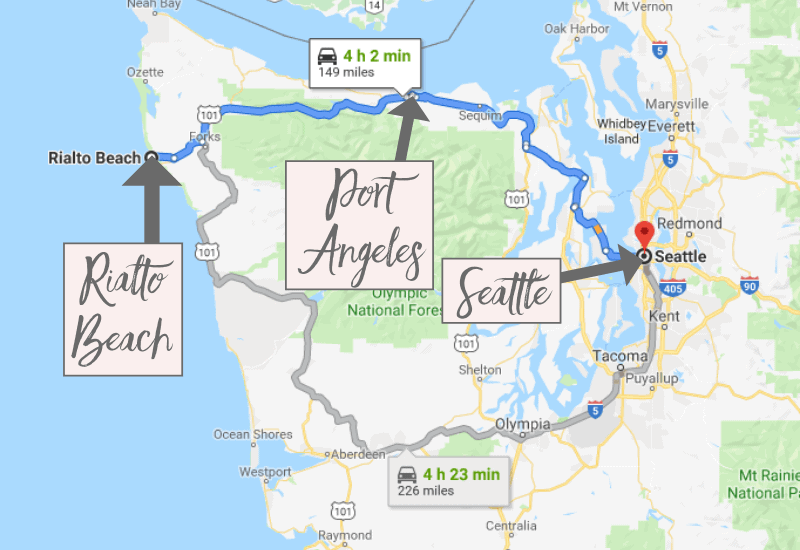

And this month we visit Washington State’s iconic Rialto Beach (RB). RB is a public beach found in the Olympic National Park, about 14 miles from the town of Forks (For Twilight fans, yes, it is THAT Forks). This map gives a good sense of the location:

(Map Source)

Most visitors walk north from the parking area for about 1 1/2 miles to reach the dramatic looking sea stacks that you see in my image above. The hike along the beach is lovely as you pass massive fallen trees and endless driftwood strewn about the coastline. If the tide is low you can also explore the tiny worlds found in the tide pools:

Just past the sea stacks erosion has created the “Hole-in-the-Wall” in a large rock that allows you to look back at the sea stacks:

Given that RB is on the West Coast the most dramatic shots are usually taken at sunset. However sunrise can offer nice scenes when the conditions are right:

At midday the light is usualy too harsh to get a nice shot but converting to B&W can help:

A sunset scene with a splash of color

Looking to get your “beach on” while visiting the PNW? Put Rialto beach at the top of your list for some great hikes, wildlife (I have seen otters near the sea stacks), outdoor camping (permits available), tide-pooling, and of course, the potential for great photography.

Pro tip: Ideal conditions will be at low tide, near sunset. Hole-in-the-Wall and tidal pools are only accessible near low tide conditions. High tide can push you off the beach and close to the massive drift wood which can be tricky to navigate/climb over. There is a hiking trail in the adjecent forest so you can still reach the sea stacks at high tide but other options will be limited.

Some good pointers on visiting Rialto Beach:

Hiking Rialto Beach to Hole in the Wall in Olympic National Park

The Ultimate Guide to Rialto Beach and The Hole In The Wall Washington

10 Best Things To Do at Rialto Beach

Until next month…m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 17-35 mm (@ 17mm), f/13, 1 sec, ISO 100,

31

Shot of the Month – March 2023

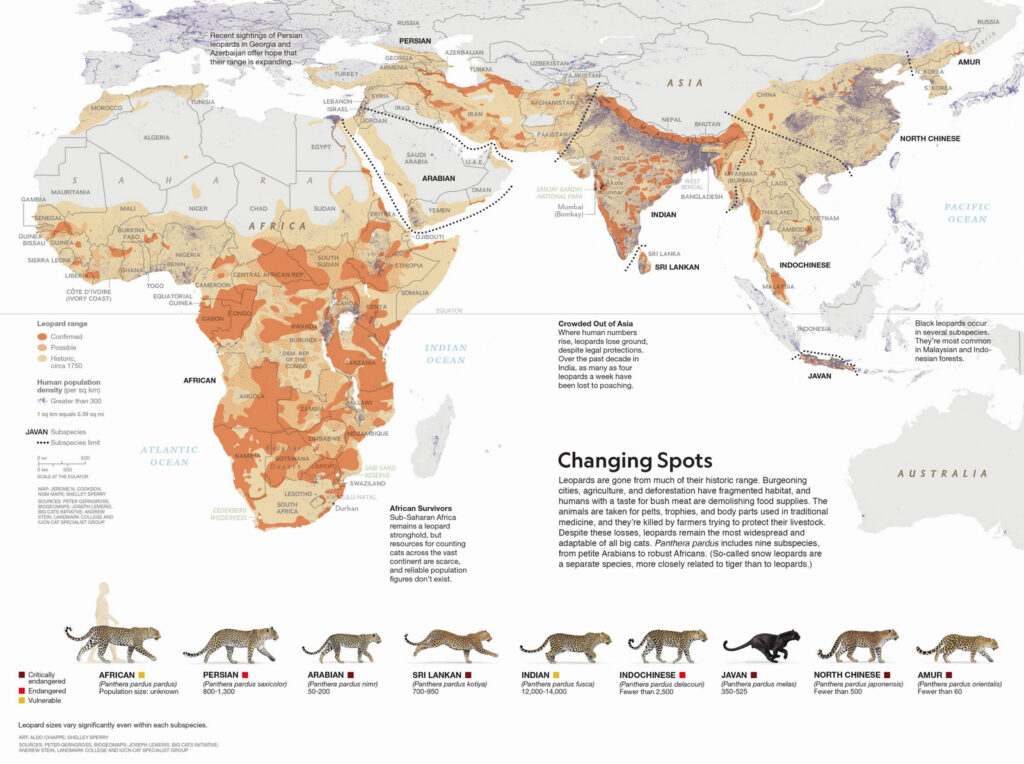

I love wild cats and I have had the good fortune of seeing lion, tiger, cheetah, serval, caracal, and the African wildcat in the wild. Of that group I am particulary partial to the leopard. Pound for pound they are perhaps the strongest of the group. Leopards are incredibly elusive and even a single sighting on a safari is a major victory. On our trip to Kenya in 2021 we had the amazing good fortune to have six leopard sightings!! I have only seen leopards in Africa but there are actualy 9 subspecies of leopard spread out across the world:

It is generally accepted that the African leopard is the most numerous species though there is no reliable estimate of their total population on the continent. India is home to roughly 12,000 leopards. Many of the other species of leopards are on the verge of extinction, however.

Individuals remaining:

Amur Leopard: 100

Javan Leopard: 250

Arabian Leopard: 200

Sri Lankan Leopard: 800

Persian Leopard: 800

Indochinese Leopard: 1000 to 2500

Leopards are stealth hunters and are renowned for their ability to carry prey up into trees to feed in peace. In the image above we found a leopard in the Masai Mara National Reserve with the remains of a Thompson’s Gazelle.

The uninitiated sometimes confuse the leopard with a cheetah. As you can see here however, the animals are quite different in size and build:

The leopard has shorter legs and a more muscular build. The cheetah (also photgraphed on the same trip) is built like a greyhound dog – long legs and a lean body. The spots on the cheetah are solid while the leopard has not spots, but rosettes. The cheetah is built to chase small prey across the open plain while the cheetah stalks in the bushes or may pounce from above while hiding in a tree.

A few more images from our trip:

A mother leopard playing with her cub just after sunrise

Another leopard with a Thomspon gazelle:

Kitty in a tree:

We found this female hunting along a riverbed just after sunrise

The color version:

The stunning leopard – its elusive magic never fails to dazzle.

Until next month….m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, f/4 1/500 sec, ISO 250, EV +1.33

28

Shot of the Month – February 2023

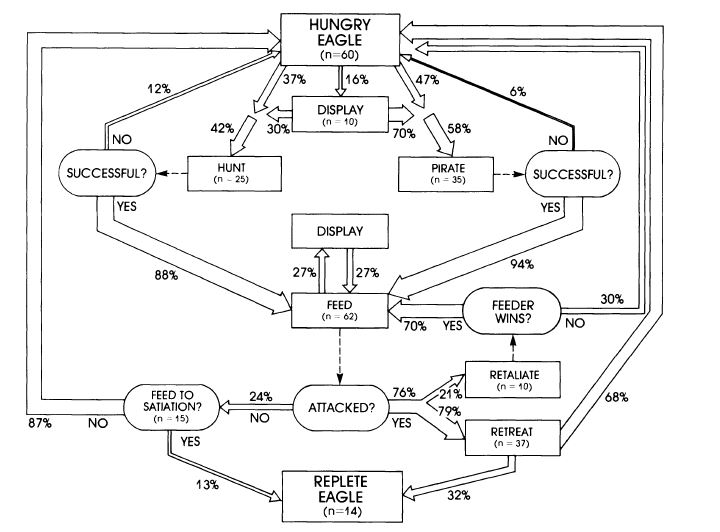

If you spend much time with Bald Eagles you quickly learn that they are quite the thieving sort. In spite of their majestic, regal looks, Bald Eagles are often gangsters in fine dress.

Check out my post, Thug Life, for more info on their wicked ways.

Even when food seems plentiful Bald Eagles will attack each other relentlessly to steal food which seems counterintuitive. Why risk injury attacking another very well-armed eagle when there is so much food available?

Armed and dangerous:

Each summer Bald Eagles congregate along the Washington coast where midshipman fish are spawning. The concentration of fish can attract dozens of eagles which then can attract dozens of photographers, like me. And each summer us photographers ask the same question over and over as we watch another eagle fight or after we see one theft attempt after another.

“Why do they do this when there are soooo many fish right in front of us”?

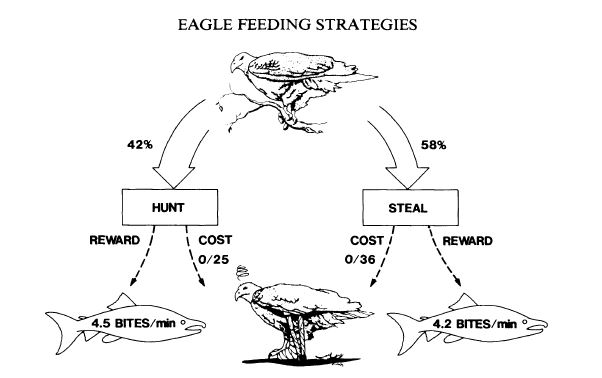

Seems that scientists have noticed the perplexing behavior also and have been trying to solve this mystery. I found a paper, “Fighting Behavior in Bald Eagles: A Test of Game Theory,” by Andrew J Hansen that was published in 1986 where the scientists studied Bald Eagles at a site in Alaska.

Some key findings (at least from this one study):

- Catching Fish = Stealing Fish

Seems that eagles that stole fish from others ate as well as eagles that caught their own fish:

Here we have an eagle catching his own fish:

2. Risk for Injury is Low

The scientists witnessed numerous attacks between bald eagles as one tried to steal from another. Surprisingly, during the study period, they witnessed zero injuries between the eagles. Despite the dramatic action the encounters rarely escalated to serious fights that can cause injury.

Eagles apparently use an array of postures, gestures and vocalizations to demonstrate both their willingness and ability to fight. Larger eagles tended to steal more often as it was clear that they were the stronger combatant. The smaller eagle would quickly acquiesce to the larger opponent and larger birds won 85% of the time.

3. Position matters:

Position was also important – a bird on the ground was always at a disadvantage to a bird coming from above in the air.

Whether a bird is positioned above or below an opponent would seem to affect it chances of winning because talons serve as the primary weapons. An aerial attacker has its feet in a position to threaten a feeder on the ground.

In the image below, the eagle on the left was sitting on the ground – at a clear disadvantage. In this encounter he leapt up to confront the attacker but as their talons interlocked the bird on the right had much more momentum and was able to flip the ground-based eagle over.

4. Communication is Important

By carefully understanding the intentions of each other, eagle interactions rarely escalate into serious battles that can lead to injury or death. Eagles will indicate their hunger level through ritualized displays. For example, in the image below we see an eagle that has thrown her head back and is vocalizing loudly — this is one of several displays that eagles can use to clearly proclaim “I am very hungry, don’t get in my way.”

The hungrier the bird, the more she will display. Other birds will see this and take this into account before deciding to attack. Or, if this bird would then go on the attack, other birds would know that she was very hungry and therefore, more motivated to fight so they might give up their meal more readily.

Fascinatingly, by throwing the head back, the eagle allows other birds to see how full his/her crop is. Another ingenious non-verbal message: “Hey, my crop is empty and I want that fish more than you do.” (A bird’s crop is an expandable “muscular pouch near the gullet or throat.” It is used to store excess food for later digestion.)

The value of a prey item to each player varies with hunger level. A bird with a crop that is nearly full can derive less benefit from a salmon than can one with an empty crop. Relative hunger level may be discernable from crop size or the length of time a bird has been eating.

Eagles apparently assessed the relative attributes of conspecifics and often chose to displace the individuals most likely to yield (small or replete birds). Pirates sometimes appeared to evaluate feeders quickly while flying overhead. Other times the birds landed and seemed to study feeders intently before attacking. The latter method may allow more accurate assessment but it is done with loss of a possible positional advantage enjoyed by aerial attackers.

At any given moment the eagles are constantly assessing size (Am I bigger?), position (birds in the air have tactical advantage over birds on the ground); and hunger level (who wants this more, me or her?) before attacking or if deciding if they should give up their fish.

This fascinating diagram from the study attempts to map out the parameters at play:

I love the scientific insights but I love photography even more. In my first image above we see an aerial attack and some nifty flying as the eagle with the fish implements a barrel roll to confront his attacker.

Here we see the same attack, just a fraction of second sooner:

Everybody wants in on this fish:

An adult Bald Eagle harassing a juvenile Bald Eagle (The adult successfully stole the fish!!).

It seems that Bald Eagles are not the reckless pirates I thought they were. Of course, I should have known better – animals are hyperaware of their surroundings and do not take unnecessary risks. Mother Nature is far too wise for that. Each Bald Eagle is constantly evaluating its best solution for finding a meal. Each bird uses a complex array of communication and observation to switch between the tactics of hunting or pirating, in a moment’s notice, depending on which approach is most favorable for the opportunity at hand.

Game on!

Until next month……m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), f/5.6, 1/1500 sec, ISO 400, EV +1.0

01

Shot of the Month – January 2023

Wow, check out this beast. He is an absolute UNIT.

This is one of the few images I have that starts to give a sense of how massive a Moose can be and demonstrate how majestic they can look.

The Moose is the monster of the deer family – it is the largest member of the deer family and is the tallest mammal in North America. A male moose can easily top 6 feet at the shoulders, and add in those antlers and this goliath towers more than 10 feet in height. Those antlers (males only) are often more than 6 feet wide and can weigh over 50 pounds. Moose are typically found in the northern regions of the United States (from Maine to Washington) and throughout Canada. Much of their height is due to their long legs that are essential to navigate the deep snow of winter found in their northern habitats. But these guys have length as well as height. Moose can easily be more than 7 feet in length and males can weigh from 1200 to 1600 pounds. It is difficult to appreciate how massive these creatures until you have one walk by you.

Photographically it is a real challenge to do these guys justice as they often just look like big brown blobs. In the winter they usually keep their head down as they graze – no point wasting energy raising those heavy antlers higher than necessary. In the winter it is all about conserving energy so moose will spend many hours sitting down, resting. Perhaps a nap here or there. Then, all of a sudden, they pop up and start to graze for an hour or so. During that brief period of activity a moose may only lift his head once or twice for a few, fleeting seconds. If you glance somewhere else, or turn to chat with a colleague and he looks up? Poof, you missed your shot. Come back in a few hours and try again! I have spent far more minutes than I care to add up staring through a viewfinder, with tears running down from my fatigued eye, as I waited for that “heads up” moment.

In this image it all came together. I managed to find a small ravine that put me lower than the moose. I burrowed down on my knees into the snow to get as low as I could go. This low angle allowed the male to tower over me, and seemingly, even tower over the mountains in the background. This angle also highlights those stunning antlers. Frequent visitors to Grand Teton National Park know this moose well and he is recognized as one of the biggest moose in the park in recent years.

In this shot he stopped grazing and stood fully up to take in his surroundings. Eureka, let the photo frenzy begin!

With the sun behind the clouds the lighting was soft and even. The light was strong enough to see the details of his dark brown fur while being weak enough to not overexpose those light-colored antlers. The snow on the ground acted as a reflector and bounced the light up into the moose’s face allowing us to see his eyes. Normally those big brown eyes are TOUGH to see and getting a bit of catchlight is even rarer.

The turn of the head gives a nice profile of his face and breaks up the outline of his body. The head turn allows us to see just how massive his antlers are. That bit of snow on his nose also offers a nice bit of contrast and depth to the image.

Speaking of depth, the snow in the foreground leads the eye to the dark moose and overall we get a great 3D effect between the light foreground, the dark moose and then again with the light shades of the sky in the background.

I love this image so much it is currently the largest metal print we have in the house. As you head down the steps to our basement you find yourself confronted by a 30″x 40″ copy of this monster.

Even though the massive print is not “lifesize” it is big enough to give a sense of the scale of a Moose. That realization stops many a guest in their tracks as they stare in awe.

Mission accomplished….

Until next month….michael

Nikon D5, Sigma 150-600 (@150mm), 1/500 sec, f/5.6, ISO 800, EV +0.667

31

Shot of the Month – December 2022

If you want to see a Mountain Goat (MG) you are going to have to put some steps in. And I don’t mean those comfortable, flat-land steps. Oh no, that won’t get the job done. We are talking about some serious vertical steps. You gotta go up, up, and more up.

These elusive creatures thrive at elevations where few other animals roam – Mountain Goats can be found at elevations of 13,000 feet (4,000 m) or more. In the photo above, taken at Hidden Lake in Glacier National Park in Montana, I got off lucky and “only” had to climb to about 6,400 feet (2000 m) in elevation to get this scenic shot. (6400 feet is about 600 flights of stairs)

By spending much of their time above the tree line Mountain Goats can avoid most predators. When they do tread to lower altitudes they can be hunted by cougars, wolves, wolverines, lynxes, and bears. Of that list of threats, the cougar is the most worrisome as they are uniquely nimble to navigate the rocky ecosystem of the goats and are large enough to overwhelm even the largest Mountain Goat adult.

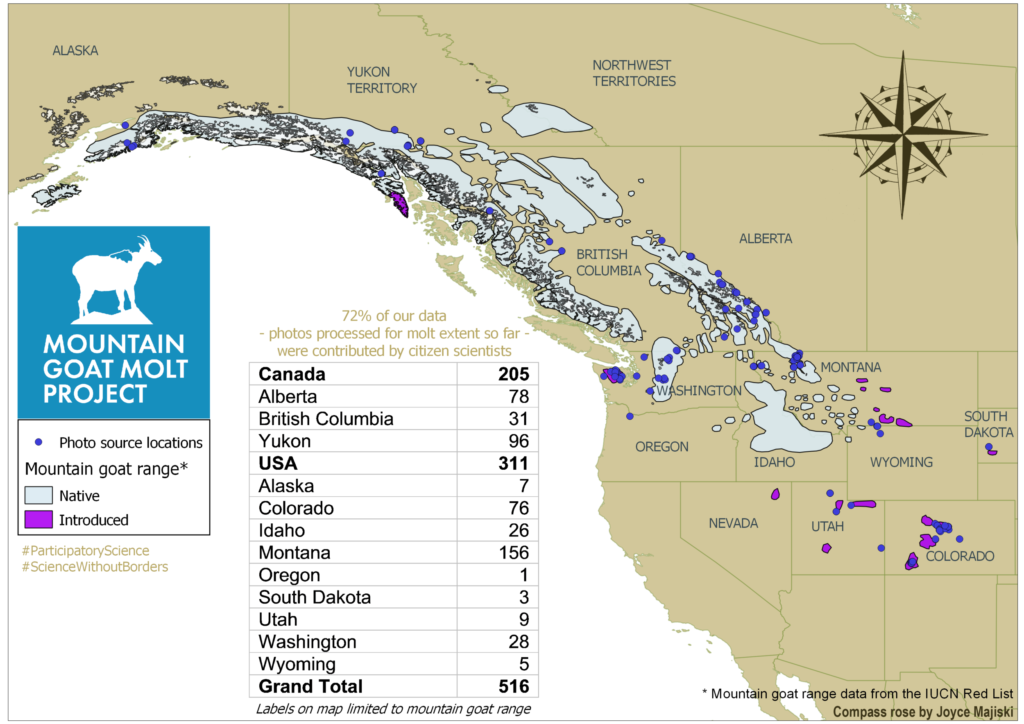

Mountain Goats are found in the alpine and subalpine environments of the Rocky Mountains, the Cascade Range, and other mountain ranges in western North America. You can find them in Washington, Idaho, Montana, and through British Columbia and Alberta, into the southern Yukon and southeastern Alaska. British Columbia is home to about half of the known population of Mountain Goats.

Mountain Goats remain one of the least-studied large mammals in North America due to the difficulty of reaching their rugged ecosystems and the creature wasn’t even mentioned in scientific literature until 1816!

Mountain Goats have been introduced, primarily for hunting purposes, into parts of Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, Colorado, South Dakota, and the Olympic Peninsula of Washington. Several of these states are now, however, starting to remove these non-indigenous populations of goats due to the adverse impact they are having on the ecosystems and other species (read more about this here). For example, Mountain Goats can introduce bacterial disease that can wipe out the indigenous Big Horn Sheep – a species that is already struggling with various threats.

In the map below you can see the historical range of Mountain Goats and the areas where the species has been introduced by humans (shown in purple):

False Advertising:

Despite their name, Mountain Goats (Oreamnos americanus) are not goats. MGs are actually in the bovidae family so they are more closely related to antelopes, gazelles, and cattle.

Mountain Goat Nomenclature:

Male MG: billy

Female MG: nanny

Young MG: kid

A group of MGs: band

Billy/Nannie??

It can be difficult to distinguish a male from a female as both sexes sport those distinctive beards and have horns. Their luscious coats can withstand winter temperatures as low as -51F (-46 C) and winds up to 99 mph (160 km/h). Female MGs weigh about 180 pounds while the males can reach 300 lbs. The horns of the female are about the same length as the male but tend to be more slender and bend back more sharply at the tip. Mountain Goats keep their horns year-round.

Like a Tree!

You can tell the age of a MG by counting the annual growth rings on their horns which are formed each winter except for the first year. (So Age = # of rings +1)

There you have it – the fuzzy wuzzy Mountain Goat – the non-goat goat intrepid denizen of the nose-bleed section of North American mountains.

Until next month….michael

Nikon Z9, Nikon 17-35mm (@ 35mm), f/5.6, 1/1000 sec, ISO 320, EV -0.667

Sources:

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

31

Shot of the Month – November 2022

WoW! Look at that amazing animal. The power it has is mind-boggling.

Oh yeah, and that brown bear in the background is pretty impressive also.

bdbdbdbdbbdbdbd-Whaaaat?

Yep, I am actually, talking about the fish. Look, brown bears are impressive and all, but Pacific Salmon (Oncorhynchus) attain an entirely different level of amazingness.

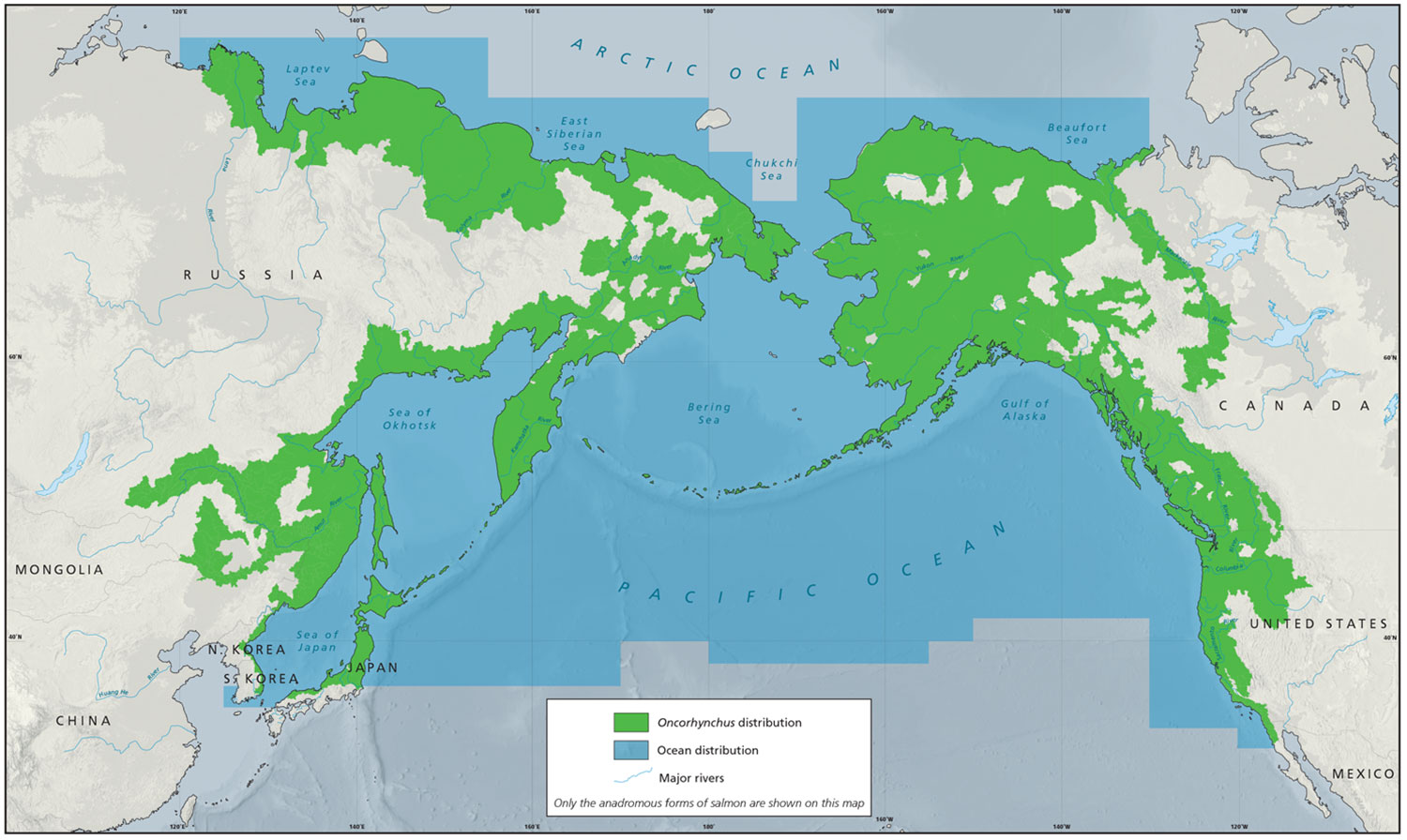

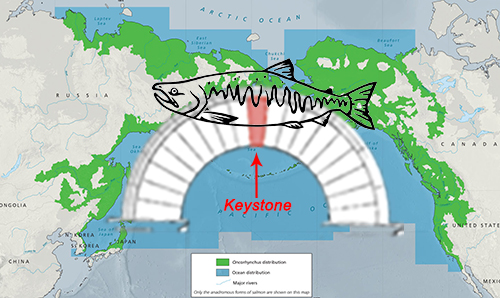

Despite their diminutive size, at least compared to a brown bear, the Pacific Salmon drives the survival of entire ecosystems across the northern Pacific Ocean as shown in this map below.

Stop for a second and let the scale of that sink in. This includes ecosystems found across thousands of miles from South Korea to Japan to Russia, across the Aleutians, and down the coastline of Alaska, Canada, Washington, and California.

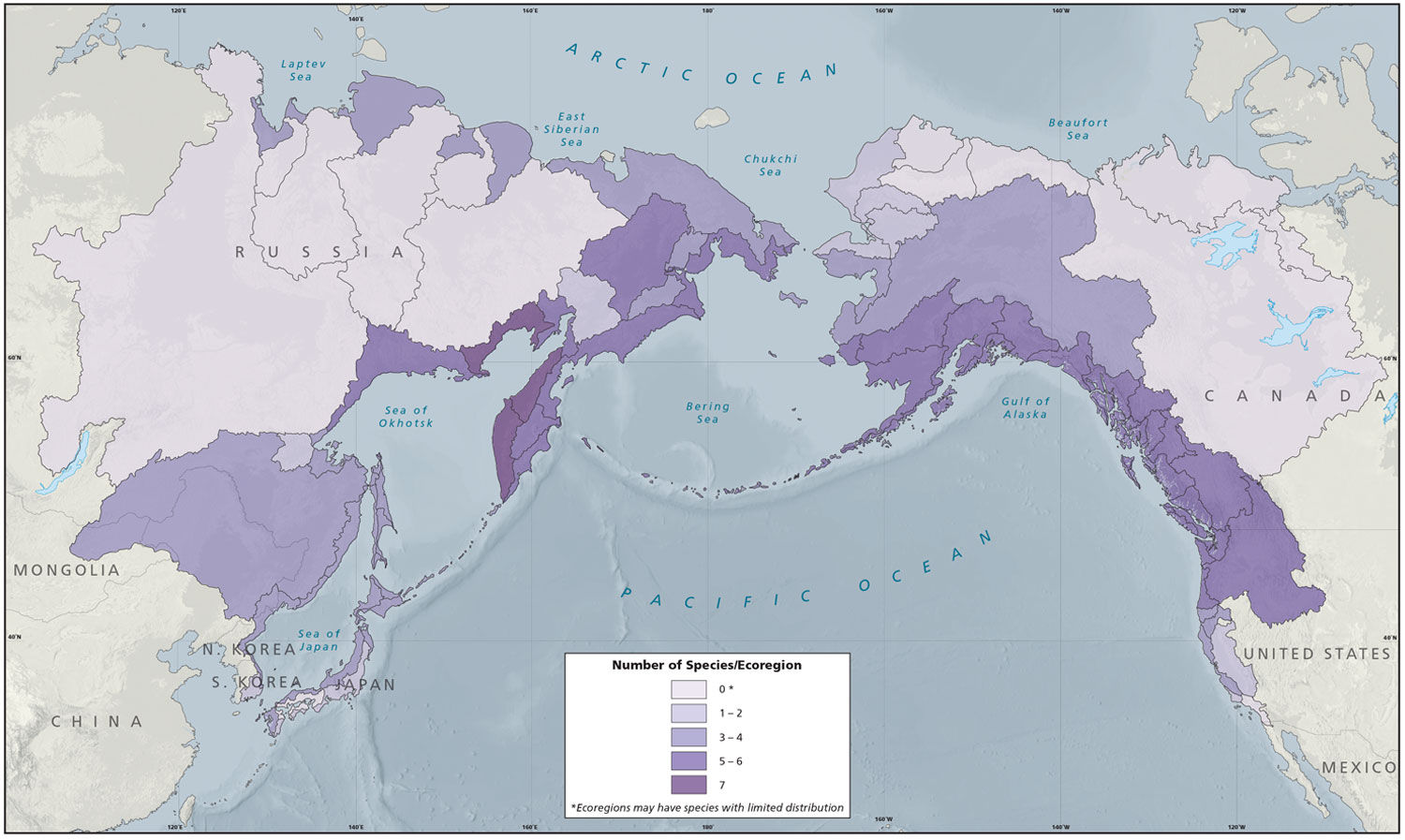

There are seven species of Pacific Salmon. Five of them are found in North American waters: chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, and pink. The other two species, masu and amago are only found in Asia. The seven species use the entire Pacific Rim coastline and can venture hundreds of miles inland in every direction from South Korea to Southern California. The coastal areas of the Sea of Okhotsk are the only regions to host all seven species as shown below.

Pacific Salmon impact so many ecosystems because of their anadromous lifestyle. Anadromous fish:

- Live the first years of their life in freshwater.

- Migrate to the ocean where food is more abundant, and then

- Return years later as adults to the same streams, where they were born, to spawn and die.

Phase 1: Freshwater to the Ocean

Pacific salmon are born in freshwater rivers and streams, and then as young fish, they begin their journey to the ocean. On this trek, more than 50% of the young salmon’s diet is insects that fall from the surrounding trees. Without the salmon there would be an explosion of insects to deal with. Salmon are the main predator of insects in aquatic environments and for this little feat alone they are Superstars. But there is more.

Phase 2: Ocean Life

Salmon gain a tremendous amount of mass while living in the rich ocean environment. As they gain mass, salmon play a vital role in the survival of key ocean species. For example, the Chinook salmon is the primary prey of the southern resident killer whale. Other ocean predators include seals, sea lions, porpoises, sharks, and lampreys to name a few. There is still more.

Phase 3: Return to Fresh Water Streams

Pacific Salmon spend 1 to 5 years in the ocean, depending on the species, before migrating back to fresh water. Each summer millions of Pacific Salmon migrate back to the streams, where they were born, to spawn and then die. The fish bring millions of pounds of nutrients from the nutrient-rich marine environment to the nutrient-poor river ecosystems. The salmon migration helps replenish the entire ecosystem, from the animals that eat the salmon, to the decomposers who break down their dead bodies, to the trees that grow from their broken-down nutrients.

For example, over 137 species of fish and wildlife depend on the Pacific salmon for survival. Of this list, 41 species of mammals rely on the salmon including orcas, brown bears, black bears, wolves, river otters and so many more. Over 89 bird species feast on salmon including bald eagles, Caspian terns, and grebes amongst others. Predators feast upon the salmon, their eggs, their carcasses, or on their young. Over millions of years, many predators have adapted their movement and behavior to take full advantage of the annual salmon migration.

In areas rich with salmon, bears will eat an average of 15 salmon/day — a significant portion of their diet. Coastal bears get 33-94% of their annual protein from the salmon. In the upper reaches of the Chilkat River in Alaska, the return of half a million chum salmon attracts thousands of bald eagles to the feast. It is one of the largest concentrations of bald eagles in the world. Wolves normally hunt for deer, but once the salmon runs start, they shift their focus to salmon. In some areas, salmon represent more than 50% of the diet of wolves.

When salmon die their carcasses provide valuable nutrients to streams and rivers.  The significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean and released to inland aquatic ecosystems. The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide significant support for invertebrates and breeding waterbirds.

The significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean and released to inland aquatic ecosystems. The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide significant support for invertebrates and breeding waterbirds.

Bears play an important role in transferring nutrients from the coast and rivers to the woodlands and forests. The bears capture salmon and feed on carcasses, and often carry them into adjacent wooded areas. There they deposit nutrient-rich urine and feces and partially eaten carcasses. Bears are estimated to leave up to half the salmon they harvest on the forest floor, in densities that can reach 4,000 kilograms per hectare, providing as much as 24% of the total nitrogen available to the woodlands. The foliage of spruce trees up to 500 m (1,600 ft) from a stream where grizzlies fish salmon have been found to contain nitrogen originating from fished salmon.

The main reason that Pacific Salmon die after spawning is to give their offspring the best chance for survival. As mentioned previously, woodland river systems along the Pacific Ocean are nutrient-poor. The rotting carcasses of the adult salmon are a major source of food for the baby fish and give them the best chance at survival. One research study showed that 40-60% of the stomach contents of young salmon could be traced to salmon carcasses. (Ewww, but, amazing)

Throughout their life cycle, salmon f-u-n-d-a-m-e-n-t-a-l-l-y transform the way ecosystems function. As predator, they keep insect populations in check. As prey, they provide essential nutrients to mammals, fish, birds, reptiles across the entire northern Pacific Rim. In death, they transfer key nutrients from the sea to inland woods needed by their offspring. But they also provide the essential chemicals that are the building blocks of entire habitats of wetlands and forests.

Because of all this awesomeness, Pacific Salmon are considered a KEYSTONE SPECIES.

Named for an architectural term—the keystone is the topmost stone in an arch that holds the entire structure together—keystone species are defined as species that have a disproportionately large effect on the communities in which they occur. They help maintain biodiversity and there are no other species in the ecosystem that can serve their same function. Without them, their ecosystem would change dramatically or could even cease to exist. (source)

This can’t be overstated – without Pacific salmon, many species, and entire ecosystems, are at risk for failure. We are seeing salmon populations drop in many locations, due to pollution, dams, logging, over-fishing, disease, etc. We are also seeing almost immediate ripple effects. The decline of the chinook salmon population is a major reason that the southern resident killer whale is now listed as critically endangered (only 76 individuals remain in the wild). In the US Northwest the declining salmon population is causing great stress on the populations of bald eagles, brown bears, grizzly bears, black bears, osprey, harlequin duck, Caspian tern, and river otter. To name a few. The salmon disappeared in McDonald Creek in Glacier National Park in 1981, and the bald eagle population plummeted from 600 to 25 in less than a decade. Today, salmon are extinct in almost 40 percent of the rivers where they were known to exist in California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Wild Salmon have declined by 90% in Washington, Oregon, and California. Hundreds of salmon runs have collapsed across the Pacific Rim.

Normally, this is where I would end with a pithy wordplay, or a bad pun, but this situation is too serious to joke about. We need the Pacific Salmon to thrive. It is not lost on me that the coastline of the northern Pacific Rim is shaped like an arch. The keystone of that arch is crumbling. Let’s hope that humanity can act quickly to protect this Superfish.

If you want to learn more and see how you can help, check out these links:

Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition

Thanks…until next month…..michael

Nikon Z9, Nikon 80-400mm (@ 260mm), f/5.6, 1/1000, ISO 900

Sources

Ecosystem Keystone: Salmon Support 137 Other Species

Pacific Salmon (Wild Salmon Center)

Salmon: a keystone species (PacificWild)

Nature up close: Salmon, a keystone species in the Pacific Northwest (CBS News)