15

Shot of the Month – June 2009

I have a collection of photos on my wall at home and at work. At times visitors or friends come by and walk along the wall and review the collection.

Some of the images provoke “ooohs and ahhhs.” Others make people laugh or smile. Some get an “eewwh” – well, some lion shots can get a little bloody, for example.

When people discover this image it tends to induce a small skit:

- Slowly walking, glance at the photo. Small recoil followed by a double take.

- Walk back and get in close for a good look. Squint a bit. Peer from the right. Now from the left

- Turn and look back at me: “What in the world is that?” or “Is that real?”

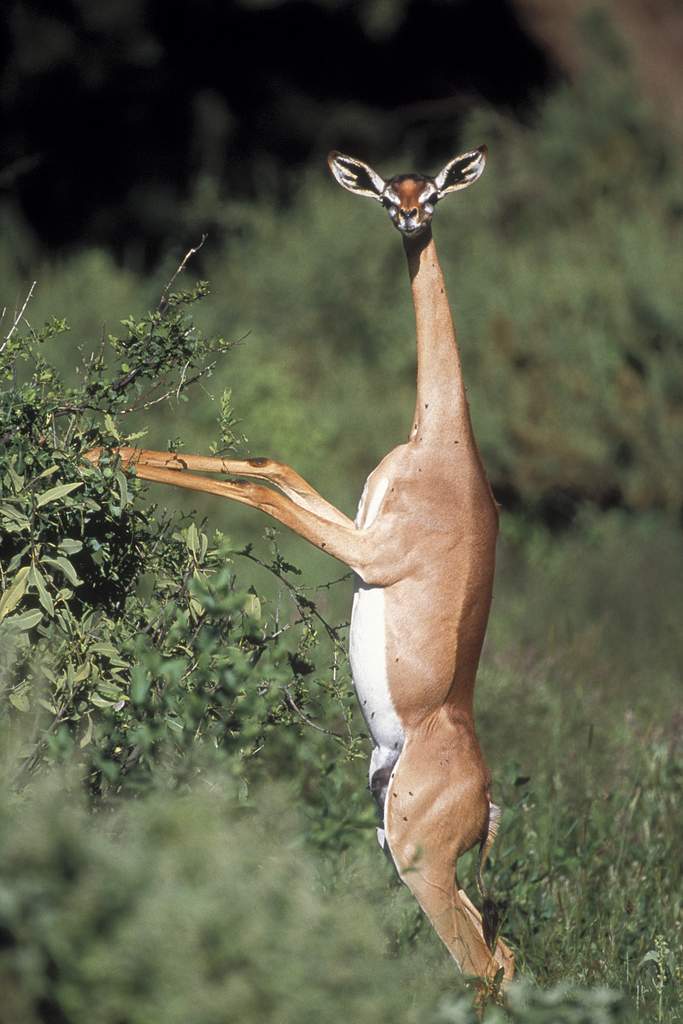

Yep, it is indeed real, and no, I did not shrink his head using some software tricks. It is all genuine and it is a Gerenuk.

Gerenuks are a type of antelope that lives in the arid regions of East Africa, typically found in eastern Kenya and Ethiopia, and parts of Somalia. The word Gerenuk comes from the Somali and means “giraffe-necked.”

What we have here is another example of keen adaptation to one’s surroundings. Changes in their spine, muscles, and bone structure allow the Gerenuk to stand up straight on its hind legs. This unique behavior, and that long neck, allow the species to exploit a very precise feeding niche. Giraffes have the tops of trees covered, while shorter antelopes and gazelles like Dik Dik, Thomson’s Gazelle, and Impala eat at the bottom half of bushes. Gerenuks saw an opportunity and adapted – by standing up and stretching their necks they can reach leaves that are six to eight feet off the ground – a feeding zone that few others can reach.

Gerenuks live in arid regions where water is scarce. Turns out that they can go months without drinking water by being very selective about what they eat. Gerenuks only eat the newest shoots and most succulent leaves of bushes and trees, often reaching into the middle branches to find the finest morsels. They also eat buds, flowers, and fruit, but they do not eat grass. This fastidious diet allows them to get all the moisture they need without drinking water and thrive in habitats where few animals can. Smart (and tasty).

While many are shocked to learn of such a beast, it seems that they have been around for a long time. Although European scientists did not discover the Gerenuk until 1898, drawings of these otherworldly creatures can be found in Egyptian art from 5600 B.C.

Hmmn, alien-looking creature. Found in Egyptian art. Some people think the pyramids could only have been built with the help of aliens. Do you think that maybe Gerenuks were, well, you know…..ok, never mind. Forget I mentioned it.

Be like a Gerenuk – find your niche and prosper.

15

Shot of the Month – May 2009

This image captures a life-and-death struggle – at least for the frog. I almost missed this epic battle – we originally stopped the vehicle to observe the spectacle of a hawk plucking and dining on a bird it had recently caught. After watching the hawk for a few minutes I started to scan the horizon – I have learned over the years that any time you stop, always take the opportunity to take in the 360° around you. You never know what you might find.

As I looked behind the vehicle, off in the distance I saw a group of Southern Ground Hornbills approaching. These large birds, about the size of turkeys, travel in groups of 2 to 7 and spend much of their time walking along looking to eat any small reptile, insect, or mammal they might scare up. The ground hornbill stumbled upon this frog and prepared to have lunch.

But the frog was not going down without a fight. If you look closely you will see that the frog has inflated himself. In this state the bird cannot swallow him – the frog is too big. Undeterred, the hornbill threw the frog to the ground and pecked at him a few times. He was trying to poke a hole in the frog’s skin so the “frog balloon” could not fill with air!

He picked the frog up. The frog puffed himself up again. No luck.

Try again. Peck. Peck. Peck. Pick up the frog. Inflate.

Peck. Peck. Peck. Inflate. Peck. Peck. Peck. Inflate.

This marathon battle lasted a good 5 to 7 minutes. Alas, at last, all the pecking had taken its toll on the frog and he could no longer inflate himself. Ironically, just as this happened, one of the other ground hornbills in the group walked over, snatched up the frog off the ground, tossed him in the air, and swallowed him whole. Gulp.

The interloper had snatched defeat (or in this case, “defrog”) from the jaws of victory.

(moan) 🙂

15

Shot of the Month – April 2009

Ever had friends come over to the house and they just wouldn’t leave? You just wanted to go to bed but they just keep chatting away, having a grand ol’ time. The look on the hippo’s face reminds me of that exasperated feeling.

“Shhh, don’t look, but are they gone yet?”

So, what is going on here? Why is this hippo out on land? Why by himself? And why covered in, uh, birds?

I came upon this hippopotamus near the Luangwa River in South Luangwa National Park, Zambia. This gigantic male is lying on a sandy flood plain above the water surface – in the rainy season he would actually be underwater, but at this time, during the dry season, the river has descended into its deepest channel and is a good 20 feet below where he is resting.

Why is he out on land? Turns out it is not as uncommon as most postcard images would have us think. Every evening hippos emerge from the water and walk up to five miles to graze on short grass across the countryside. Hippos will also bask in the sun during the day for short periods (gotta break up all that napping somehow).

Why is he by himself? Although the classic African scene is that of a group of hippos, a “pod” for those of you keeping track, lounging along the river’s edge, it turns out that hippos are not social animals. They do not develop social bonds with the other members of the pod and scientists don’t really know why they huddle together. Perhaps, they are just following the old adage of “safety in numbers.”

And why is he covered with birds? These are Red-billed Oxpeckers. Despite the somewhat annoyed look on the hippo’s face, he actually welcomes their presence as they provide a valuable service. Oxpeckers pick off ticks and other annoying insects that can’t be reached otherwise.

But there is more to this story. Hippos are very aggressive and males often fight each other for dominance. If you look closely this huge male is covered in fresh, open wounds. My hunch is that he was in a vicious brawl the night before and didn’t fare too well. Exhausted, bloodied, and bruised he took refuge up on the raised bank of the river to rest and heal in peace. The oxpeckers, looking for a free meal, will continually check the wounds for insects and help keep them pest-free. Everybody wins, right?

Well, some scientists now believe that the oxpeckers, in fact, may also peck at the wounds to keep them open so they can drink the blood directly, thereby delaying the healing process. So, depending on the situation, the hippo-ox pecker relationship may be “symbiotic” and in other situations “parasitic.”

Or in less zoological terms, sometimes oxpeckers act like Florence Nightingales (get it?) and other times they act like feathered vampires. At this point, no one knows for sure where the truth lies.

Life is complicated……

15

Shot of the Month – March 2009

You gotta respect the attitude of this colorful fellow. It’s as if he is glancing over at us and cooling asking “And what, exactly, are you doing on my rock?” This would be attitude a la Agama – agama lizard to be precise.

Unlike many creatures on my website, agama lizards are far from being endangered. I have seen them in Gabon in West Africa, in Kenya and Tanzania in East Africa, and in most places in between. There are 31 species of agama lizard spread out across Africa.

In my first visit to Africa, as a Peace Corps volunteer, we called them the “push-up lizards.” Why? Well, the males, that would be the colorful ones, have this habit of running hither and thither, stopping abruptly, and for what seemed to be for no apparent reason would start to do push-ups. Of course, we all know now that this is all about boys being boys – the males were trying to show off to the lady lizards and/or scare off rival males. By bobbing up and down they were trying to appear larger than they really are.

Agama lizards live in a very hierarchical world. In a given space the most colorful agama will be the dominant male or “cock.” Subordinate males adopt a dull brown color. A dominant male can have up to six females in his territory for breeding. We’ve all seen lizards splayed on rocks basking in the sun–even this has its rules in Agama land. You will find the dominant male at the highest position on the rock, followed next by the sub-males, and lowest on this literal totem pole you will find the females.

Male agama lizards will fight each other to hold or take over a territory. A challenger will present himself in full splendid Technicolor – a visual cue that he is here to rumble. It is a scene many of us can recall from high school dances or from often repeated scenes at the local bar. First, the two rival males make eye contact – brows furrow. Soon there is a lot of huffing and puffing at a safe distance. Then the head bobbing thing. Then full body push-ups. If the challenger has not fled away or returned back to monochromatic servitude then the dominant male will charge closer to within a few inches. More bobbing. Finally the two charge each other, and then, well, and then they flip around in opposite directions. Have they lost their nerve? No, facing away from each other, tail to tail, allows the sword, uh, tail fighting to begin. They lash at each other until one is sufficiently pummeled and flees. Apparently, some biting can also occur, but that seems rather unmanly to me.

So there you have it, the glorious, albeit ridiculous, agama lizard – the life form that high school jocks come back as in their next life. (For those who believe in reincarnation)

Until next month… 🙂

14

Shot of the Month – February 2009

This month I offer a scene emblematic of the primary holiday of the season (sorry to disappoint all you Ground Hog Day fans) – Valentine’s Day.

In this romantic scene, we have the male Kori Bustard courting a female. As part of the courtship, he provided her with a steady stream of grasshoppers. He seemed quite adept at this as I saw him give her 3 tasty morsels in just a few minutes. Apparently, some males offer snakes as large as 2.5 feet in length as gifts!

Kori Bustards have dramatic courtship rituals where the male will stand straight as an arrow on the top of a small hill and inflate his esophagus to create a brilliant white plume around his neck, as shown on the left.

Kori Bustards have dramatic courtship rituals where the male will stand straight as an arrow on the top of a small hill and inflate his esophagus to create a brilliant white plume around his neck, as shown on the left.

When walking he will also lift up his tail to highlight the white feathers (as shown in the photo to the right). All this is to make a striking visual display. He will sometimes emit a low-pitched boom to add sound effects to the spectacle.

All this commotion can attract several females. Alas, it must be told that the male Kori Bustard is polygynous – a nice way of saying that he will mate with as many of the fine ladies as he can. And once courtship is complete, the female is left to her own devices in raising the young.

For all of you celebrating Cupid’s day might I suggest chocolate or flowers over grasshoppers, and avoid that polygynousness.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

15

Shot of the Month – January 2009

If you look at this photo and go “Whoa! This guy is scary!” then I have succeeded.

I chose this shot because I feel that it best captures the seething danger embodied by the Cape Buffalo (CB).

Let me repeat,

C-a-p-e B-u-f-f-a-l-o.

Not water buffalo.

While these animals may look similar, they are two very different creatures. The water buffalo lives in Asia, not Africa, is slightly larger, and has been domesticated. Only about 4,000 wild water buffalo exist in the world and they are declining fast. There are however about 140,000,000 domesticated water buffalo gently wandering around India (over half live there), Nepal, Pakistan, Bhutan, and Thailand. These animals have been domesticated for over 5,000 years and are used by farmers to toil fields and provide essential meat and milk to humans. Their dung can be used as fertilizer and fuel when dried.

Cape buffalos live only in Africa, have never been domesticated, and many consider them to be one of the most dangerous animals in the world. CBs have the honor of being one of the “Big Five” – a phrase used by big game hunters to describe the most difficult and dangerous animals to hunt on foot. Many hunters consider the CB to be the most dangerous of this illustrious group. The reason why? Well, let’s imagine that you are a hunter who shoots a Cape buffalo but the injury is not fatal. Most wounded animals would do their best to hide in the bush or slink away and recover. Not the Cape buffalo. Well, he will sneak away into the bush – not to hide, but to begin his assault on you. He will stalk you. He will follow you. He may circle back on the trail and ambush you from a different direction. He won’t stop until he has gored you or stomped you to death. The hunter becomes the hunted.

So, uh, avoid ticking off a Cape buffalo.

Counter to what you might think, if you were walking through the bush and stumbled upon a herd of buffalo you would most likely be safe. Cape buffalo feel safe and confident when in a herd so they do not feel the need to charge unless seriously provoked. It is the lone buffalo that you need to worry about. Male buffalo get irritable as they get old (like many of their human counterparts) and typically will leave the herd and live a solitary life. If you find a buffalo on his own he may be injured, sick, or in the case of old males, just plain cranky. Regardless of the cause, a lone buffalo will feel insecure and threatened when encountered and will often lash out. Stay very, very clear of a lone buffalo.

Cape buffalo are fierce fighters and when attacked often respond as a unified force. There are many reports of herds of buffalo fighting off hunting lions. One such scene has been caught in a now-famous YouTube video. Click here to see the luckiest Cape buffalo calf in the world:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LU8DDYz68kM

Bonus: A reward for those of you who stuck it out to the end of this missive. Here is the list of the “Big Five” (I know it has been driving you crazy). In no particular order:

- Lion

- Leopard

- Rhino

- Elephant

- Cape Buffalo

Happy New Year!

15

Shot of the Month – December 2008

Given it is December I thought I should look for an image that is consistent with the holiday season. The best I could come up with was this photo of some African reindeer.

Ok, ok, they’re not reindeer. They are Gemsbok. Also known as Oryx by some.

And they definitely are not at the North Pole — Gemsbok are typically found in some of the hottest spots on the planet and thrive in the deserts, scrublands, and brushlands of Africa. These chaps were photographed in Botswana in the Kalahari Desert.

Besides their spectacular looks, these creatures are a wonder of adaptation – every aspect of their existence from body shape, to specialized organs, to behaviors, to diet has been perfected to allow these antelopes to survive where most other animals would perish.

While it may seem counterintuitive, being large (about 55” at the shoulder, and up to 550 lbs) helps to survive in the desert. Their surface area is small in proportion to their mass so they do not heat up nor cool down as quickly as smaller animals.

Gemsbok have learned to graze at night when the moisture content of grasses and plants is higher. This allows them to get water when none can be found elsewhere for months at a time. This behavior also allows Gemsbok to be less active during the hottest part of the day. During the day they retreat to the shade whenever possible to avoid overheating. At times they will lie down in the shade with their belly on the cooler sand.

No shade available? In this case, Gemsbok are careful to keep the smallest part of their bodies turned to the sun and the biggest part to the breeze. Their white bellies help to redirect heat and solar radiation from the hot sand away from their bodies.

And we are not done yet. Gemsbok have two more amazing adaptations up their black and white sleeves.

Most mammals maintain a steady body temperature and release heat by sweating. When water is plentiful Gemsbok also sweat and maintain a constant body temperature. But when water is scarce they cannot afford to lose precious moisture in this fashion so they stop perspiring. They reduce some of the heat by panting and the rest is absorbed by allowing their body temperatures to rise by as much as 7° F to 113° F – a temperature that would cause brain damage in most mammals and kill them. Why doesn’t it kill the Gemsbok?

Did you notice the long snout on these fellows? Turns out that the snout is filled with a maze of blood vessels that act like a car radiator. A network of blood vessels is surrounded by veins carrying blood that has been cooled by evaporation from the nasal passages as the animal breathes. As warm blood from the heart passes through this network it is cooled as it exchanges heat with the surrounding veins and lowers the temperature of the blood going to the brain. This heat exchange mechanism can keep the brain 5° F cooler than the rest of the body – the margin between life and death.

Pretty cool, huh?

May you all have a cool yule and a groovy New Year.

15

Shot of the Month – November 2008

This month I highlight a stunner of the bird world – the Carmine Bee-eater. I love the name, and find that I cannot say it without applying a poor imitation of a Brooklyn accent (think Rocky, and replace “Adrian” with “Carmine”).

Of course, those of you with a more refined education already know that “carmine” is by definition “A strong to vivid red,” or “A crimson pigment derived from cochineal.” ( I didn’t know….)

As you can see, it is an apt name for this scarlet fellow. Carmine Bee-eaters (CBEs) can be found in east and southern Africa though I have personally only ever seen them in Botswana and Zambia.

Most shots of the CBE on my site are from a safari I took in Zambia and most have this tan backdrop—it is sand. I found a vertical sandbank along a river that was riddled with row after row of holes, which can be up to 8 feet in depth I am told, that CBEs had dug to house their next brood of chicks. They must raise their chicks quickly while the river level is low—once the rains return the sandbank will be underwater.

Each day I would drive to this spot along the river and I would get out and spend at least an hour peering down from above watching the birds come and go. I shot hundreds and hundreds of images trying to capture these speedsters as they rocketed in and out of the sand bank. CBEs are exceptional flyers and routinely catch insects out of the air. It really is no contest. Once I saw a large moth make the fatal mistake of flying near a colony of nesting CBEs. A barrage of CBEs exploded out of the battery. The moth was dive-bombed relentlessly and it was lunch in a matter of seconds. The CBE in this photo has captured a plump insect and is returning home to feed the waiting chicks.

Carmine Bee-eaters are a stunning shade of red that is accentuated in sharp contrast by a metallic-green head and aqua-blue lower back. And if you catch them just right in the light, you can see that their wings are translucent.

At times dozens of CBEs burst from the side of the river simultaneously– a startling cacophony of movement and hue – an airborne crimson tide that the mind’s eye will not soon forget.

Until next month….:-)

15

Shot of the Month – October 2008

The story behind this image is not so much about the technical challenges in getting it, there weren’t many, but rather about people’s reaction to it.

This photo is perhaps the most popular image that I have in my collection. People always respond strongly to it – most comments begin with some verbal variation of “awwwhh….”

I had seen this zebra behavior for many years but could never actually get the shot — by the time I could stop and get set up to take the photo the zebras would invariably move, raise one head, or make some other movement that would ruin that perfect symmetry.

This shot was taken in Tanzania, during a hot afternoon. With the sun high in the sky the lighting was about as bad as it can get—the light was dull and drained of color. As we came around a corner I saw that the plain was full of zebras. I immediately stood up through the open roof of the vehicle and began to scan the horizon. I knew from previous experience that zebras often displayed this behavior under these types of conditions. Within a few seconds, I saw the outline of these two zebra and quickly told the driver to stop before we got too close. I threw the bean bag on the roof of the car and quickly squeezed off a shot with my lens set at its maximum range of 800 mm. A second later the zebras moved. I took more shots but only the first one came close to the ideal. It is often like that—the first shot is your only shot.

I actually find this shot rather, well, boring. The colors are not very interesting. I just don’t find it very compelling. But this is an example where an especially powerful behavior trumps aesthetics.

People react strongly to this shot. Some give a little gasp. Others cooo. People find it highly romantic, cute, endearing, loving–you get the idea.

For the romantics in the crowd, read no further, as I am about to give away the ending. The reality is that this behavior is less about camaraderie than it is about survival. It gets tiring standing out there on the plains all day, especially during the hottest part of the day. It would be great to sit or lie down but that is very dangerous with lions, cheetahs, leopards, and hyenas on the prowl. So, zebras will stand astride resting their head on their neighbor’s back. This takes the strain off their neck while still maintaining their diligence in looking for predators. The “hug” position ensures that no predator can sneak up on them since, as each is looking in the opposite direction, together they have a full 360-degree view of the plain around them.

Zebra are actually quite ornery, ill-tempered creatures. The males especially are always nipping at each other, fighting, kicking, biting, and engaging in just about any other anti-social behavior you can imagine. In zoos, zebras typically are kept away from the other animals as they have a habit of biting off the other animal’s tails.

The zebra hug, love, or just survival? This world could definitely use a few more hugs, so let’s just keep it as our little secret.

15

Shot of the Month – September 2008

I am always striving to get the “perfect” photo that captures the essence of the subject at hand. For each type of animal, I have the image in my head and I am eternally looking for it to appear before me. This photo of a Malachite Kingfisher comes very close to that unattainable goal.

I have long marveled at this tiny burst of color with wings. They are small, fast, and usually seen only briefly, typically at far distance rendering any thought of a photo as useless. My portfolio was woefully lacking a good shot of this fellow.

Malachite kingfishers live along bodies of water, typically rivers. I rarely had an opportunity to photograph them. This shot was the highlight of a trip that I made to Zambia a few years ago. Overall the trip was not great for photography—generally, I had seen few animals, even fewer predators and I was rather depressed about it all.

At my last stop of the safari I spent a few days at a camp on the edge of the Zambezi River. The game drives were producing little so I decided to take an afternoon off and explore the river. I had seen a couple of malachite kingfishers on a previous outing and I decided to stalk them and see if I could get something worthwhile.

For the next three hours my “pilot” and I cruised slowly among the reeds looking for a flash of color. It was a cloudy day and a bit windy. I was not pleased about the dull light but it proved to be a blessing—the subdued light allowed the colors of the bird to really pop out.

So, there I was lying down in the middle of the small boat. I had several bean bags stacked up on the small metal bench I was supposed to sit on while my 300-800 mm lens rested across the bags pointing forward. When we saw a bird we would bring the boat around and head either straight for him or within a few feet of him. As we approached the bank I would have the pilot turn off the engine so we could coast in. This stopped the vibration from the motor allowing me to shoot, and hopefully made us stealthier and less likely to scare the bird away.

Crouched down in the bottom of the boat I had a very narrow angle of movement with the lens. As we got closer I would try and shift around and keep the bird in the viewfinder as long as I could. Eventually, we would slide into the bank and/or into the reeds. Sometimes the wind would blow us off course. As we approached I would be shooting feverishly, continually adjusting the focal length of the lens until I was either too close or the subject flew away.

Sometimes the wind would rock the boat or cause mini waves. The lens was always ready to detect the slightest movement and many shots were blurred. Invariably there would be plants, leaves, branches, and other obstacles between me and my quarry.

We would approach, shoot, shoot, shoot….bang into the bank…bird flies away. Repeat.

Repeat

Repeat. Repeat. Repeat….

A huge lens in a small boat on a windy day trying to shoot a very, very small bird hiding among the long leaves and reeds on the bank of a river. Not a recipe for success, but very effective in causing cramps, sore neck, watery eyes, and the assorted cursing of “un-niceties.”

It only takes one great shot to make it all worthwhile. And this is it. This image really captures the spectacular beauty of the malachite kingfisher. His stunning blue and aqua cap. And those red feet—startling. His beautiful fluffy orange chest all brought into sharp relief with a lovely green backdrop. And all this is in focus and is very sharp and crisp. Did I mention that I was using a lens that magnifies the slight hint of the possibility of movement? On a small boat? Windy?

Another small miracle—well two really: the bird itself, and getting this image.

I have learned over the years that every safari gives you something special. Sometimes it just appears before you and other times you have to try something different and be willing to adapt to the opportunities you find. And often you have to be prepared to work for it.

In this case, it worked out brilliantly.