15

Shot of the Month – December 2011

Woodpeckers are the avian jackhammers of the wild. When at work, looking for food, or building a new home, their telltale sound is unmistakable. Rat-a-tat-tat. Rat-a-tat-tat. Rat-a-tat-tat. Rat-a-tat-ouch–that-makes-my-head-hurt-just-thinking-about-it. Tat.

There are about 200 species of woodpeckers distributed around the world, though oddly, none are to be found in Australia. I photographed this Golden-tailed woodpecker in Botswana. This African species can be found across much of Southern Africa and in some isolated pockets of East Africa.

On a given day a woodpecker may strike a tree with his beak 8,000 to 12,000 times (up to 20 times/second). With each blow, the woodpecker experiences 1200 g of force. Is that a lot? For reference, humans pass out at 4 to 6 g’s of force. We get a concussion with a deceleration of about 100 g. (Geek Note: One g is the acceleration due to gravity at the Earth’s surface and is the standard gravity (symbol: gn), defined as 9.80665 meters per second squared, or equivalently 9.80665 newtons of force per kilogram of mass. Yawn)

How exactly do woodpeckers move around so easily in the trees and do what they do without knocking themselves out? Seems that woodpeckers have developed some nifty adaptations:

Avoiding Brain Damage (always a good idea)

- Thick Skull: Woodpeckers have a thick skull with spongy cartilage at the base of their beak. This spongy base absorbs much of the force.

- Strong Muscles: Woodpeckers have developed very strong muscles that attach the upper and lower jaws to the skull. By contracting these muscles a millisecond before contact the woodpecker diverts some of the impact to the base and rear of the skull.

- Accurate Strike: The woodpecker does a very good job of whacking (yes, that is the technical term for it) his target at a very precise ninety degrees. This perpendicular strike reduces torque which could cause a concussion.

- Small Brain: Woodpeckers have relatively small brains for birds of their size. The small ratio of brain weight to brain surface area allows for the impact to be spread over a large area, reducing the risk of damage.

Hmmn, thick-skulled and small-brained…make your own joke here ____________

Other nifty adaptations:

- Safety goggles: Just before contact a nictitating membrane (a transparent third eyelid) closes, protecting the eye of the woodpecker from flying wood chips. This membrane also acts like a seatbelt holding the eye in place – given the tremendous deceleration of the head the bird’s eye could literally pop out without this extra support.

- Kick Stand: Woodpeckers have a stiffened tail that is useful for climbing and foraging. They can use the tail as a prop.

- Knarly feet: Woodpeckers have zygodactyl feet, allowing them to walk up a tree easily. If you look closely at the image you can see these feet in action. Zygodactyl feet have 2 toes that point straight forward and 2 that point backward.

The wondrous woodpecker. Probably not the bird to call if you need help with your homework, but definitely look him up if you want help remodeling the kitchen.

Until next month… 🙂

15

Shot of the Month – November 2011

This month we visit with one groovy, chillin canine – a Black-backed Jackal (BBJ) sitting in the sun in the Kalahari Desert in Botswana. Look closely at his face. His serenity appears sublime.

I have seen many black-backed jackals and such moments are rare. More typically I have seen them, usually two, as they tend to form life-long partnerships, scampering along with great purpose. No time to spare. Looking for the next meal. Perhaps hurrying home to feed the pups. Other times scampering to avoid danger from a leopard or other predator. Occasionally a restive jackal, but more often than not — scampering.

BBJs are cunning and exceptionally quick. They can dash in and steal a morsel of food before a dining lion has noticed what happened. Ok, that is quick, but these guys are QUICK. Our guide Simon told us about the time he was asked to help sedate a few jackals with a dart so a local scientist could take some measurements. For this exercise, they had to use blow guns to deliver the darts as a rifle would generate too much force on a canine that only weighs about 20 pounds.

Simon loaded the long tube, found his target, and fired. Pfffft. And the dart was off – faster than anything you or I could see. The jackal, hearing the sound, looked over and at the last instant, scooted his butt out of the way and seemed to watch the dart as it flew by. Ok, lucky move. Reload.

Pffft.

Again, at the last moment, the jackal stepped aside like a matador as the raging bull dart missed its mark. (Is he the “One?”)

They never managed to dart a single jackal.

Life on the plains is rarely restive, nor predictable. Dozens of times over the years I have seen lions feeding at a kill – many of those times BBJs watched from a few feet away, waiting their turn at the scraps. The lions never seemed to notice, let alone care, except one time in Tanzania several years ago. We watched as the lions finished off a carcass and then sauntered off for a nap. A BBJ finally moved in for a snack. To my amazement, one of the lions got up and began to stalk the jackal. The jackal was unaware. The lion launched his attack, but the jackal, using the above-aforementioned quickness, managed to escape. But boy, was that one annoyed jackal. He barked up a storm in the direction of that lion as if some unwritten code had been violated.

Stalking lions. Dart-zinging humans. It’s a jungle out there. When scampering along in your own jungle, remember to seek out Zen moments like the one captured here where you can.

Let’s try. Oooommmm. Oooommmm. That’s right, stop and relax. Light a candle. Sit lotus style (if your joints will allow it). Deep breath. Clear your mind. Innnnnhaaaaale. Exhaaaaaaale.

If you get it right, the only sound you might hear is that of your soul catching its breath. (I’ll keep my eye on the lion for you…)

Until next month…

15

Shot of the Month – October 2011.

Is it just me or when you read the name of this antelope does it make you think of a bumper sticker that might look something like:

Yeah, ok. Probably just me.

(For those of you playing at home, the “beast” in my bumper sticker is Dr. Henry Philip “Hank” McCoy, the Beast from the X-men comics.)

I grant you that the hartebeest is a bit odd looking but the reviews out there are tough. One site said that hartebeests are “ungainly antelopes, readily identified by the combination of large shoulders, a sloping back, a glossy red-brown coat and smallish horns in both sexes.” Another commenter said that the hartebeest, “ …at first glance seems strangely put together and less elegant than other antelopes.” Yes, all true, but not something we really say in polite company.

The taxonomy of this grass eater is complicated as it seems to be for many animals. There are about 6 sub-species and 2 separate species of hartebeest spread out in generally isolated pockets across Africa.

Roll call:

Subspecies: (this might be a good time to break out your atlas)

- Bubal Hartebeest: They used to live in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Yes, used to. We killed the last one around 1923. (Extinct)

- Coke’s Hartebeest: Found in Kenya and Tanzania

- Lelwel Hartebeest: Found in Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda (Endangered)

- Western Hartebeest: Found in limited numbers in West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo.

- Swayne’s Hartebeest: Ethiopia (Endangered); Somalia (Extirpated)

- Tora Hartebeest: Found in Eritrea and Ethiopia (Critically Endangered); Sudan (Extirpated)

Separate Species:

- Red Hartebeest: Found in Namibia, Botswana, South Africa

- Lichtenstein’s Hartebeest: Found in Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe

I photographed this Red Hartebeest in the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park in Botswana.

So what is the difference between a species and sub-species? Animals from different subspecies (of the same species) are capable of inbreeding and producing fertile offspring. They usually don’t interbreed due to geographic isolation. For example, Coke’s Hartebeest, the most prevalent version found in Kenya and Tanzania, could breed with Swayne’s Hartebeest, found only in Ethiopia, but they don’t as their territories do not overlap and these antelope do not move around much.

I think the hartebeests have developed a bit of chip on their shoulder about what us humans have been saying about them. Time for a little payback from a Red Hartebeest. (Note: A male hartebeest can weigh up to 350 pounds).

Follow this link

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2oymHHyV1M

or watch here:

Ouch. How is that for elegance? Now that’s one badass even-toed ungulate.

Until next month…. J

15

Shot of the Month – September 2011

I never could really keep it straight in my head what the difference was between a stork, heron, egret, and, well, between just about any other tall and lanky feathered thing. I have just done a bunch of reading on the subject and I would like to say that it is now all perfectly clear. It isn’t. I have learned however that the whole naming-of-animals thing is a rather messy affair. Here is what I know.

There are 64 species of birds that are considered herons. We call some herons, others egrets, and the rest bitterns. But they are all herons.

I photographed this elegant heron in Botswana. Given that it is predominantly white we call it an egret, even though there is no real biological distinction between a heron and an egret. But if a heron is white, or has some decorative plume feathers, we usually call it an egret. For the record, this is the Great Egret, aka, Great White Egret. There are four sub-species of Great Egret spread across the globe with one in Europe, one in the Americas, another in Africa, and the fourth found in India, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

And what about bitterns? “ Webster says that they are “any of various small or medium-sized usually secretive herons.” LOL. Well, that sounds pretty scientific. Probably more useful for identification, bitterns tend to have shorter necks than most “typical” herons.

Another useful tidbit. Herons fly with their necks retracted as opposed to storks, ibises, and spoonbills which fly with fully elongated necks

And remember, when all else fails, “Look at that pretty bird” works just fine.

Until next month… 🙂

15

Shot of the Month – August 2011

No introduction is required for this fellow.

The tiger is one of the most widely recognized animals in the world. Humans have been mesmerized by this apex predator for thousands of years. You could spend a lifetime cataloging all the historical, mythological, religious, literary, and cultural references to the tiger.

The tiger is one of 12 Chinese zodiac animals. It is an earth symbol. Tigers are the national symbol for at least 6 countries and are found on many national flags. Tigers are an important symbol in Buddhism. Tigers play every sport you can imagine: the Detroit Tigers (baseball), the Balmain Tigers (Australian Rugby), the Sunipret Ice Tigers (German Hockey), the UANL Tigers (Mexcan soccer), and well, there are hundreds more. Elvis thought they played a bit rough and the “Eye of the Tiger” gave Survivor a #1 song in 1982. A tiger was an important character in The Jungle Book, was a buddy of Pooh, and a tiger was found on a lifeboat in the Life of Pi. Calvin’s best friend was a tiger and a tiger named Tony helped sell a lot of cereal. From cultural god to Wall Street hawker, the tiger has been voted, at least in one poll that included 73 countries, as the world’s favorite animal. Yes, even more popular than Lassie and her canine brethren.

Normally from here, I would attempt to beguile you with a host of fascinating facts and tidbits about the tiger’s amazing physical traits or abilities. Or regale you with the challenges and risks of getting this photo of a Bengal Tiger in Ranthambore National Park in India –there were a few.

But none of that matters. What matters is that you understand how completely and utterly we have destroyed a species that we seemingly love and admire so much. Take a marker and color in most of Asia on a map – a huge swath of the land mass of our planet. That is where tigers used to live. Now tape that map on the wall and throw 6 or 7 darts at that colored area. That will give you a sense of the space where tigers now have to live.

In 1900 there were 100,000 tigers in the wild. There are now around 3,000.

In just more than a lifetime 97% of tigers have been wiped off the planet. The Bali tiger went extinct in the 1940s. The central Asia tiger vanished in the 1970s. We killed the last tiger in Java in the 1980s. The South China Tiger was killed off in the 1990s (a few still exist in zoos). The six remaining subspecies are struggling to survive.

We are destroying the forest they need to live in. We hunt and kill them to make aphrodisiacs. We kill them to make coats.

Wow, imagine how we would treat the tiger if it wasn’t our “favorite” animal!

People are finally starting to notice. Leaders from the 13 countries where tigers still exist attended the Global Tiger Summit in St. Petersburg, Russia in late 2010 to launch a campaign to try and double the population of tigers by 2022. India has been working for quite a few years to try and protect its tigers from poaching and has been increasing the areas that are protected for tigers. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has been working tirelessly to raise awareness.

Unless we take action soon, tigers will become our favorite memory.

Want to do something to help? Click here for ideas from WWF on actions you can take.

15

Shot of the Month – July 2011

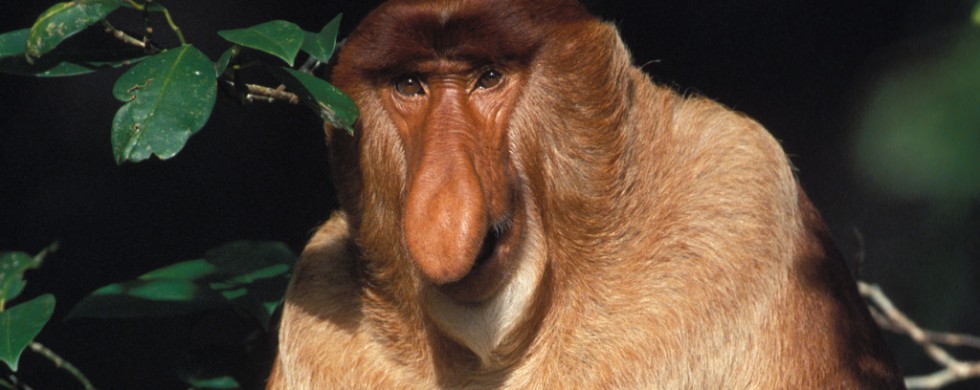

For five days and nights, our wooden boat worked its way up the Sekonyer River through the oppressive heat and pallor of the Kalamatan jungle on the Island of Borneo. (If you can remember Martin Sheen’s trip up the Nung River in the Cambodian Jungle in “Apocolypse Now” you will have a good sense of what the conditions were like – though, luckily, without the gunfire.)

The primary goal of the trip was to see orangutans but along the way, we spotted this homely fellow, a Proboscis monkey, among the trees along the river’s edge.

Pro-what? New word for Michael. For you other non-scrabble players:

Proboscis: /proʊˈbɒsɪs/) an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate, e.g. the trunk of an elephant or the feeding tube of a butterfly.

Scientists aren’t sure but they assume that the larger the nose, the better the luck in attracting the lady monkeys. Go figure. The females also have largish noses but they are not as pronounced as in the males. Proboscis monkeys have the largest noses of any primates. The male vocalizes through the nose with a kee honk sound. Really, I couldn’t make this stuff up.

And a gentle reminder, it is not polite to stare.

Adding to the Homer Simpson look, the Proboscis monkey has a pot belly. Their stomachs are large to accommodate several compartments that use bacteria to digest the cellulose of the leaves of mangrove and pedada trees. When full, the stomach can represent 1/4th of the animal’s body weight! These leaves represent 95% of their diet.

Dining primarily on leaves allows the monkeys to remain safely high up in the trees and avoid predators lurking on the ground.

Proboscis monkeys are agile climbers but they are also quite at home in the water. They can often be spotted walking upright across stretches of water in the mangroves. Fishermen have even spotted the monkey swimming up to one mile offshore in the ocean. Proboscis monkeys actually have partially webbed feet – a testament to how much time they spend in or near the water.

In Indonesian (Borneo is part of Indonesia) this monkey is named orang belanda which means “Dutchman.” Seems the locals thought the Dutch, who colonized this part of the world, often had large noses and pot bellies like their local monkey. Sounds like payback if you ask me.

There you have it, the web-footed, pot-bellied, elephantine-esque primate otherwise known as the Proboscis monkey. Another beautiful, uh, well, striking sight from the natural world.

15

Shot of the Month – June 2011

This month we visit with the (Southern) Pale Chanting Goshawk (SPCG). Doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, does it?

I had never heard of such a bird and I was surprised when I first spotted this striking fellow while visiting the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana. SPCGs are distributed across southern Africa and prefer dry, open semi-desert environments. That would explain my lack of exposure to this fellow — I had not visited many southern African countries and I had explored even fewer game parks located in or near the deserts of these countries.

You can see in this lower photo the dapper marking of this raptor. Take note of the fine striped chest and leggings. His chest is an exquisite, delicate grey. And throw in a striking dash of color with those orange legs and black and orange beak. On several occasions, I almost injured my neck as I snapped my head around as my eyes were drawn to an orange beacon at the top of a tree or bush. Each time it was an SPCG. In the late afternoon light, already rich with hues of orange from the sun, his beak and legs seemed to glow with an other-worldly force.

SPCGs dine primarily on lizards, but will also eat small mammals, birds, and large insects. When hunting the SPCG will often land near his prey and then chase his victim down on foot.

It’s a ridiculous sight really, watching such a large bird sprint from here to there and back again like something out of a keystone cop film. The effect is even greater given that the bird is gussied up like some gangster from the 1940s. Throw in a pair of suspenders and his retro mobster look would be complete.

And who says that Mother Nature doesn’t have a sense of humor…?

15

Shot of the Month – May 2011

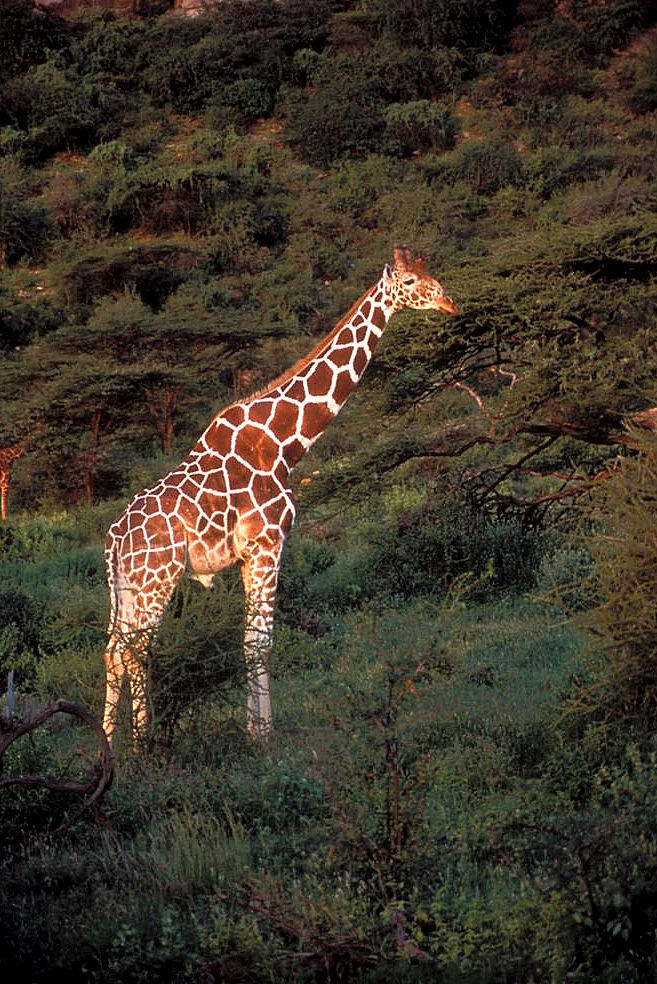

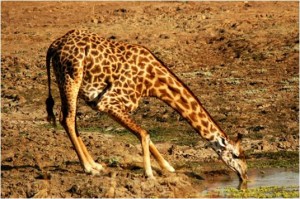

Many would look at the image above and say that it was a picture of a giraffe. While this statement would be generally correct, it would also be unfair, or at least unsatisfyingly vague. Many might not realize that there are in fact 9 types of giraffe in the world (all living in Africa) and each is a bit different than the others. The specimen above is a Reticulated Giraffe and is only found in northern Kenya, Somalia, and southern Ethiopia. I photographed this one in Samburu National Park in Kenya. The Reticulated Giraffe is one of the most common varieties found in zoos.

The creature having a drink below is obviously also a giraffe but his/her markings are clearly different. This is a Thornicroft Giraffe that I photographed in South Luangwa National Park in Zambia. There are only about 1,500 Thornicroft Giraffes left in the world and they all live in eastern Zambia.

“Giraffe” also includes:

Nubian Giraffe: Only about 250 remain in the wild and they are found in eastern Sudan and northeastern DR Congo.

Smoky Giraffe: About 20,000 are left in the wild and they are found in southern Angola, northern Namibia, and parts of Zambia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe.

Kordofan Giraffe: Less than 3,000 remain in the wild and they are found primarily in Chad, Central African Republic, and Cameroon.

Maasai Giraffe: These are the giraffes that most people see if they go on safari in East Africa. There are about 40,000 left in the wild and they are found in Kenya and Tanzania.

Rothschild Giraffe: Less than 700 remain in the wild though they are zoo favorites so there is a good chance you have seen one there. In the wild they live in Uganda, parts of Kenya, and in southern Sudan.

South African Giraffe: Less than 12,000 are left in the wild and they are found in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique.

West African Giraffe: These are the rarest giraffe in the world with a population of less than 220 left in the wild. They are found in southern Niger.

Each sub-species of giraffe has a unique size, color, pattern, and distribution. The next time you see a “giraffe” be sure to dig a bit deeper to find out which particular natural gem you have discovered.

🙂

15

Shot of the Month – April 2011

Do you have someone in your family or perhaps a friend or two in which everything about them seems bigger than life? The way they dress, the way they act, how they talk, the stories they tell, the situations they seem to find themselves in? Well, if you were a bird, your buddy the Hoopoe would be that over-the-top pal. The one shown here was photographed in Botswana.

Check out his dramatic style. His wings and back are painted with striking black and white markings. The head and neck are adorned in a beautiful hue of gold. And then there is that headdress. When excited he will snap it open with great flair and may bob his head up and down to ensure that all take notice.

And these guys really get around. They can be found in Europe, Asia, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. Like true jet setters, those from Europe and north Asia will migrate to warmer temperatures in the tropics during the winter.

Fly in a straight line like the rest of us birds? No, too pedestrian. The hoopoe has a distinctive style – by closing his wings every few beats his undulating flight pattern bobs up and down much like how a cast-away bottle rises and falls with the ocean swells.

Birds spend their time in trees, right? Well, the hoopoe spends much of his time on the ground foraging for something to eat. He uses that long, slightly curved bill to detect and extract insects, particularly insect larvae and pupae, from the soil. Hoopoes are fond of crickets, locusts, beetles, cicadas, and so forth but will occasionally dine on small reptiles, and frogs and may partake in seeds or berries.

And then there is the fighting. Hoopoes are very territorial and the males get into brutal fights and will try and stab each other using those long bills like daggers. Some birds have been known to be blinded during such battles!

Other over-the-top behavior? Oh, there’s more. Female hoopoes raising young produce a foul-smelling liquid that they rub over themselves while in the nest. The young, mother and the entire nest smell like rotting meat. Scientists posit that this wretched liquid deters predators and may act as an antibacterial agent.

And the hoopoe chicks have a very endearing trick up their sleeves. From the age of six days, nestlings can fire streams of feces at intruders and they can hiss like snakes to try and scare off would-be attackers. (Thanks, but I’ll pass on babysitting those little darlings)

And hoopoe are such hobnobs — humans seem to be fascinated by these starlets. Egyptians considered them sacred and their likeness can be found on ancient tombs and temples. Hoopoes are mentioned in the Bible and Koran alike. In Persia hoopoes were a symbol of virtue and they were prominent in the Persian book of poems “The Conference of the Birds.” And they are the national bird of Israel. Harrump. Show-offs.

Such flair, energy, and panache. Yes, hoopoes and their ilk can be tiresome at times. But, I think we all need a few hoopoes in our lives to remind us to dare to be bold and embrace life.

Until next month. 🙂

15

Shot of the Month – March 2011

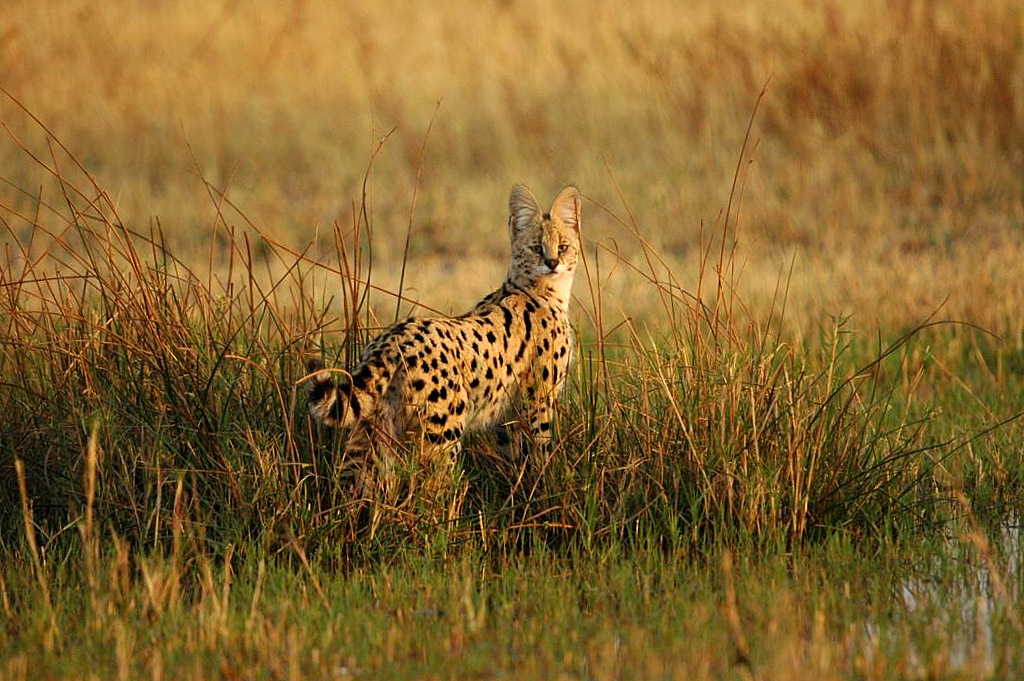

While all felines are apex predators and rest comfortably at the top of the food chain, most of our attention and admiration go toward the “Big Cats” – lion, tiger, leopard, and jaguar. These are the largest members of the feline family and they are the only ones that can roar. Some folks add the snow leopard, mountain lion, and cheetah to the Big Cat list. (For the record, none of these classifications have any scientific standing)

Then we have the 35 species of “lesser cats.” A term I would find insulting if I was among this group as each of them is quite spectacular in their own, diminutive way. The serval, as photographed here from Botswana, is one such wonder.

Servals are shy and normally out at night so they are rarely observed. We found this one just as the sun was about to rise on a crisp morning in Botswana. Given that servals only stand about 2-3 feet tall they are especially hard to see in tall grass. That is, however, unless they are hunting.

During one safari in Namibia I was slowly driving along when I heard the loud chatter of angry birds. The clatter finally broke through my consciousness and I remembered that sounds can be an important tool in finding wildlife. Why all the racket? Why were these birds so upset? I stopped the car and listened. I followed the sound to the enraged birds and watched as they hovered above the tall grass.

BOING. A serval exploded from the grass in an amazing vertical leap. He leapt up and forward—most likely trying to land on an unsuspecting mouse. BOING. Another amazing vertical leap. BOING…One of my favorite safari memories. Ever.

Servals specialize in locating and eating rodents with their exceptional hearing and sight. And with that amazing jumping ability. Servals can use this skill to leap 10 feet into the air from a sitting position to catch birds in flight! They also dine on fish, lizards, frogs, and insects.

And these cats are good at what they do. Lions are only successful about 30% of the time when they hunt. Serval hunting success rate is 50%. Take that Big Cats!

The mighty serval –the Tigger of the savannah.

Until next month… 🙂