30

Shot of the Month – June 2014

Whoever named the Red-winged Blackbird (RWB) didn’t take much time at the task. Sure, the name is accurate, but come on, really? By that measure, the American Robin would be called the Orange-bellied Thrush. Where’s the creativity?

Whoever named the Red-winged Blackbird (RWB) didn’t take much time at the task. Sure, the name is accurate, but come on, really? By that measure, the American Robin would be called the Orange-bellied Thrush. Where’s the creativity?

A more interesting nom de guerre perhaps? How about the Spartacus Swamp Sparrow? Yes, that has a certain ring to it.

Let’s Break it Down (Hammer style?):

Spartacus: RWBs are the gladiators of the cattails. During the breeding season, a male spends at least a quarter of the daylight hours defending his territory. Each day the male finds the highest nearby perch and rigorously calls out his claim on the surrounding little piece of the Earth as he provocatively flashes his red epaulets for all to see. (To be completely accurate, one must acknowledge that the epaulets often have a yellow or orange border)

Check out this video to hear and see one in action.

Females are attracted to the males with the brightest and biggest epaulets (hmmp, typical).

From his perch, the male aggressively defends the nest from all adversaries. These guys are known to take on animals, and certainly birds, much bigger than themselves as you can see here. This bald eagle apparently came too close to the RWB’s home turf and Spartacus came at him with a vengeance – I have a whole sequence of images of the RWB dive bombing and circling the eagle. Alas, the eagle never took notice of the robin-sized warrior.

Such an antagonistic attitude is well founded given the dangerous world RWBs live in. Just about every North American raptor preys on RWBs — short-tailed hawks are particularly fond of dining on them. Even barn owls who normally prey on small mammals are in on the take as are Northern Saw-whet Owls who are barely bigger than the RWB! Crows, ravens, magpies, and herons sometimes prey on blackbird nests. Other predators of the nest include raccoons, mink, foxes, and snakes. Marsh wren will destroy the eggs and peck the nestlings to death. You can see why RBWs have a chip, albeit a colorful one, on their shoulder.

Swamp: RWBs prefer wetlands and can live in both freshwater and saltwater marshes. That being said these guys are adaptable and can be found in just about any open grassy area and can even be found in dry upland areas where they will live in meadows, prairies, and old fields. They have a massive range and can be found as far north as southern Alaska and as far south as the Yucatan peninsula. Those living in the north will migrate to the southern US and Central America in the winter.

Sparrow: RWBs are not really in the same family as sparrows – I took some artistic, alliterative license with that one. In my defense, however, the female RWB looks like a large sparrow. The bland colors of the female allow it to blend in nicely and not draw any undue attention to the nest.

Given the relentless onslaught from predators and rivals, from both land and air, one has to admire the plucky Red-winged Blackbird. In my book, he has definitely earned his stripes.

Until next month….m

31

Shot of the Month – May 2014

Having moved to Vermont a few years ago I knew that one of my photo projects would be to try and get a decent image of one the marquee mammals of the American Northeast – da moose. Such projects begin with desk research, or more accurately nowadays, Google search. I scoured the internet for images of moose to get a sense of what’s possible, the best places to go, when to go, and so forth and so on. I was surprised by how few, really interesting images that I could find. Moose are large, rather gangly, and brown (similar to my dilemma with elephants, err, large and gray). Moose are most active in the early morning or late afternoon so the light can often be very dark, which is not good when your subject is already brown. A brown moose, standing still, in lackluster light. B-O-R-I-N-G. Fun to see in person, but not a recipe for a noteworthy photo.

The best images I found were either taken with a moose in water or with a moose captured among the fall colors.

Based on my findings I imagined the “ideal” shot — I wanted to get an image of a bull moose standing in the water (lake, pond, or river would do) with water cascading off his massive antlers with a mountain forest covered in glorious autumn colors as a backdrop. Piece of cake…

I learned that Maine was probably the best place to find moose in New England so I researched potential guides and called one to see if we could come to an arrangement. I described my ideal shot. The guide, admirable in his restraint, patiently explained why that combination of elements was pretty close to impossible.

What this flatlander boy didn’t realize was that Moose don’t have antlers year-round. Bull (male) moose grow antlers starting in the spring and reach maximum size in the fall — just in time to battle other bulls for the right to mate with cow (female) moose who are coming into season. With the rut over the antlers fall off at the beginning of winter as they are no longer needed and would be a huge burden (they can weigh 50 pounds) walking in the deep snow during a period when food is so scarce. During the summer moose feed heavily on aquatic plants that are rich in sodium. They will wade into a pond or lake and pull up lilies and pondweed. Some moose will even dive underwater to reach some plants.

So here’s the rub. Want big antlers and bright fall colors? Late September is the time to get that shot. Want to find a moose eating in the water? That happens during the summer, June-August. By the time fall colors have arrived, most water lilies and aquatic plants have stopped growing so it will be really, really hard to find a moose feeding on them at that time. Early in the summer moose can “regularly” be found in water dining but usually their antlers are fairly small and not fully developed.

So, there I was in Maine’s Baxter State Park, with low expectations on an otherwise lovely June day when this bull moose walked out into the pond and began to dunk his head for a meal. What he lacked in antler size he made up for in action. Every once and a while the moose would shake his head like a dog to shake the water off (Note: This was the ONLY moose I have seen do this). Just the extra element I needed to take a “nice” photo into the realm of something special.

Most of the time the moose was standing perpendicular to my position so I could not get the full effect. Mother Nature finally smiled upon me and the moose turned in my direction and decided to rinse off. I held the shutter button down and kept firing as long as I could. I instantly knew that I might have captured something special.

One may go many days, months, or even years in effort before those split-second opportunities flash by. But one of the greatest joys of photography, when successful, is that I can relieve that spectacular moment each day as I walk upstairs and pass by that image hanging on my wall. 🙂

Until next month…

30

Shot of the Month – April 2014

This month a visit with the “hooked-nosed sea pig.” I know them sounds like fight’n words but this description is simply the translation of the scientific name of the Gray Seal, two of which are shown in this photo taken off the coast of Maine.

This month a visit with the “hooked-nosed sea pig.” I know them sounds like fight’n words but this description is simply the translation of the scientific name of the Gray Seal, two of which are shown in this photo taken off the coast of Maine.

Halichoerus grypus = hooked-nosed sea pig

Check out the profile of the guy in the water and you can understand why folks in Canada also refer to them as the “horsehead” seal.

Males tend to have a dark brown-grey to black coat with a few light patches. Females are generally light gray-tan, lighter on the chest, with dark spots and patches. Based on this, I posit that we have a male in the water and a female resting on the rocks above.

Gray seals are large — they are 8-10 feet in length and can weigh between 370-680 pounds. Males can be twice the size of females.

Gray seals eat many types of fish though sand eels are a particular favorite. They can eat 11 pounds of food per day and can dive up to 250 feet in search of prey. The seals are opportunistic feeders and will eat the occasional sea bird, octopus, lobster…

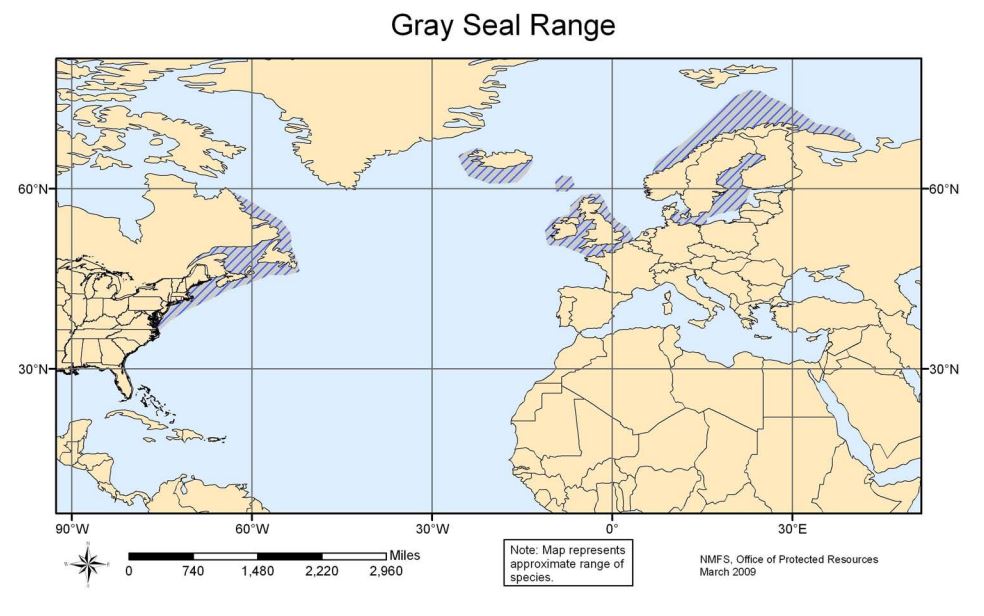

The gray seal lives in three distinct populations (total global population is about 300,000):

1. Western Atlantic (population 150,000): Eastern Canada and Northeastern United States

2. Eastern (130,000 – 140,000): Great Britain, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Faroe Islands, and Russia

3. Baltic Sea (7,500)

Have a hard time remembering the difference between sea lions and seals? I feel your pain. Here’s the skinny.

The term “seal” is rather vague and captures a range of creatures that are categorized into 3 taxonomic families.

1. True Seals (Phocidae): There are 18 types of true seals — members of this group do not have visible ears and use a belly crawl to get around on land. Gray seals are member of this family.

2. Eared Seals (Otariids): There are 15 types of this seal — members of this group can rotate their hind flippers forward and “walk” on land. They also have pinnae. Sea lions are found here.

3. Walrus (Odobenidae): The only member of this family is the walrus. The walrus is easily recognized by its large size and tusks.

Sea Lion True Seal

So, all sea lions are seals. But not all seals are sea lions. Got it? If you are still confused, here is a nice article on the differences.

When it comes to seals, the gray seal, however, is the real deal.

Until next month….m

31

Shot of the Month – March 2014

In the Northeast, you know that Spring is just about sprung when your local berry tree is suddenly just, a tree. What happened to the berries? Most likely, Cedar Waxwings is what happened.

In the Northeast, you know that Spring is just about sprung when your local berry tree is suddenly just, a tree. What happened to the berries? Most likely, Cedar Waxwings is what happened.

With the change of seasons marauding hoards of Cedar Waxwings, returning from warmer locales, descend upon a laden tree and devour all the fruit in 1-2 days before moving on to the next buffet location.

I shot this photo by two fruit trees just outside of my office building in February 2014. The scene was comical as suddenly a few dozen birds would appear and the berries started “poppin.” Standing underneath the trees I was repeatedly pelted as berries bounced off my head as some fell loose or as the birds cast aside those fruit deemed unacceptable.

Cedar Waxwings are one of the few North American birds that specialize in eating fruit and are considered mainly frugivorous (yep, it’s a word).

In the early summer, they eat strawberries, mulberries, and serviceberries. By later summer they have shifted to raspberries, blackberries, cherries, and honeysuckle berries. In late fall and winter, they forage for juniper berries, grapes, crabapples, mountain ash fruits, rose hips, cotoneaster fruits, dogwood berries, and mistletoe berries. (source)

That’s a lot of berries.

Because they eat so much fruit, Cedar Waxwings occasionally become intoxicated or even die when they run across overripe berries that have started to ferment and produce alcohol.

During the summer Cedar Waxwings will supplement their fruity diet with protein-rich insects like mayflies, dragonflies, and stoneflies that they often catch on the wing over water, “flying like tubby, slightly clumsy swallows.” (I love that description)

While most birds hatch in early summer, the Cedar Waxwings nest in late summer to ensure a rich supply of berries for their young.

During the mating season, males often pass a small item like a fruit, insect, or flower petal, to the female. After taking the fruit, the female usually hops away and then returns giving back the item to the male. They repeat this a few times until, typically, the female eats the gift. (source)

Ahhh, the mighty berry — it determines where Cedar Waxwings go, when they go, helps in finding a mate, and influences how they raise their young.

Let the games begin:

28

Shot of the Month – February 2014

The highlight of our trip to Yellowstone National Park in January 2014 was the 45 minutes we watched 3 North American River Otters along a mostly frozen river.

The highlight of our trip to Yellowstone National Park in January 2014 was the 45 minutes we watched 3 North American River Otters along a mostly frozen river.

I challenge anyone to watch an otter for 10 minutes and not have his/her spirits lifted. Watch an otter family and the time drops to 2 minutes or less before one’s worries are whisked away.

Of course, I may be a bit biased in this assessment — I have been known to hang out at the otter display at the zoo for an hour or more, captivated by their antics.

Otters seem to infuse a sense of joy into everything they do. They never seem to miss an opportunity to rub against a member of the group and share affection. And “play” is a big part of otter life for both young and adults alike. At Yellowstone, we watched as the otters bounded through the snow like a mustelid Tigger. The otter in my photo seemed to have a grand ol’ time as he slid up and down the skeleton runs they had created in the snow.

It was like watching a frenetic winter decathlon — at any given moment one otter or another was diving into the swirling currents (probably hunting for fish, their preferred food), stopping for a quick nuzzle with a sibling, running and sliding on a nearby drift, popping out of the rapids for a good shake, and so on.

I could have watched all day.

Otters are best seen in action. A few videos to brighten your day (at the risk of otter overload):

Yellowstone otters doing what they do best (the narrative is a bit cheesy…):

Cutest otters E-V-E-R (show this one to your children and be sure to watch till the end):

Otter and dog friendship:

Otter rock juggling:

31

Shot of the Month – January 2014

I had the good fortune to visit Yellowstone National Park a few weeks ago (January 2014). The dramatic landscape of mountains, rivers, and forests is painted in primary hues of white (the Snow!), much white; but also blue (the Sky!), green (the Trees!) and brown (the Wildlife!). I saw my first wild American Bison. You can’t fully appreciate how big these creatures are until one walks within 20 feet of you. The bison herds were one of our more constant companions. We saw them each day, often with their heads deep in the snow looking for a meal.

A bison herd at the base of a mountain along the bend in a river. Driving snow. Quick, someone call Norman Rockwell.

Once I got back I was looking forward to learning more about the bison and sharing some tidbits with a photo.

But then it went, less well.

In my research, I rediscovered those facts that I learned so dispassionately as a child. It went something like: There used to be lots of bison in the West. We killed most of them. The West was won and we became a great country.

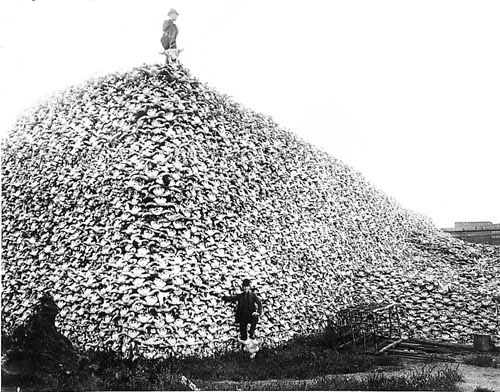

This time, however, it was much more personal. Let’s go back to the killing part. There used to be at least 50,000,000 bison in North America. They may have been the most numerous large animal on earth.

Fifty million. F—i—f—t—y M—i—l—l—i—o—n.

Mull that over for a bit. As America rushed to “settle” the West in the 1800’s the bison were a nuisance. The onslaught began. The railroad companies didn’t like how the bison were causing delays to their trains and damaging their tracks. The companies ….” offered tourists the chance to shoot bison from the windows of their coaches, pausing only when they ran out of ammunition or the gun’s barrel became too hot.”

Bison killing contests were held. A Kansan set a record of killing 120 bison in 40 minutes. For mind-splitting irony, listen to the Kansas state song while you read on. “Buffalo” Bill Cody was hired to exterminate bison and managed to kill 4,000 in 2 years of effort. In just one winter (1872-73) the demand for bison hides in the East drove professional hunters to kill 1.5 million bison (source).

The US government actively promoted the extinction of the bison as a way to destroy the Plains Indians whose entire way of life was based on the food and materials provided by those herds. Troops were ordered to kill bison at will. In 1874 President Ulysses S. Grant vetoed a Federal bill to protect the dwindling bison herds. In 1875 General Philip Sheridan pleaded to a joint session of Congress to slaughter the remaining herds in order to defeat the Indians (source).

In less than 100 years the slaughter was complete.

By 1890 there were less than 1000 bison left. (Estimates range from 541 to 750 individuals)

The number of wild bison alive today is about 12,000. The largest wild herd in the US is found in Yellowstone and includes about 4,000 animals.

You may have heard that there are 500,000 bison and while that number is correct, don’t be overjoyed. Other than those 12,000 all the rest are raised in private commercial farms like cows and have often been crossbred with cattle.

I photographed the bison above during a heavy snowfall. I have brightened the image to cause the snow to consume the bison around the edges. I added grain to the image to give the sense of looking at an old photo of a time long past. I don’t want you to see the true bison because it doesn’t exist anymore. Only a notion of that creature remains. The bison that was, a member of a herd that covered a continent, is no more. We worked really hard to scratch that animal out of the American landscape and no park, no matter how magnificent it is, can make that right again.

I am not sure which is more powerful, my sadness or my rage, over what we did to this amazing creature. Or, over what it says about my species.

31

Shot of the Month – December 2013

Each December many children’s heads are full of ideas of what presents they would like a certain someone from the north to bring them. Although I had left such thoughts behind long ago, this year I received a wonderful gift from the north just in time for the holiday season. My gift skipped the flying-reindeer-driven-sleigh thing and flew in under its own powers to allow me to get my first sighting, and photograph, of a Northern Hawk Owl (NHO).

Each December many children’s heads are full of ideas of what presents they would like a certain someone from the north to bring them. Although I had left such thoughts behind long ago, this year I received a wonderful gift from the north just in time for the holiday season. My gift skipped the flying-reindeer-driven-sleigh thing and flew in under its own powers to allow me to get my first sighting, and photograph, of a Northern Hawk Owl (NHO).

NHOs normally live in the boreal forests across the northern Holarctic so it is pretty rare (though not unheard of) to see one this far south. This little stunner has been hanging out in a nearby town (about 25 minutes away) since mid-December though I was not able to go see him until just before Xmas. This NHO flew hundreds of miles south from the desolated arctic landscape and perplexedly made his winter home in a series of fields right beside a very busy road. He seems completely unfazed by all the commotion. He could often be found sitting at the top of a dead tree (as in this photo) as the traffic buzzes by. I have seen him catch at least 5 rodents within 30 yards of the traffic so the noise must not bother him.

This guy can sure draw a crowd. On separate days while out shooting I met excited birders who had driven up from Pennsylvania and/or New Jersey (6 hour drive one way) to get a glimpse of this fellow. Every day, not too safely, I had more than a few cars stop on the road as the driver leaned through the open window and asked in a gasp, “Do you see HIM?” Their glee was immediate as I pointed him out. They would then quickly pull into a parking area 100 yards up the road and scurry back with assorted binoculars, spotting scopes, and/or cameras. At times traffic was almost brought to a halt as drivers slowed to try and understand what all the commotion was about while others tried to look around and see what we were all looking at. The crowds usually did not last too long given how bitterly cold it often was. The flurry of activity would ebb and flow as one group saw and left as another hopeful group arrived. Your average visitor spent perhaps 12 minutes gazing in wonderment or waiting for a better view. I typically spent about 4 hours at a time during the five days that I visited the site trying to get a good shot.

How did so many people hear of his arrival? All things can be found on the internet, grasshopper. As word got out the pilgrims came from all around Vermont, New York, Maine, Massachusetts… I met a friendly couple from Chicago who were visiting family in Vermont. I met a nice young woman, Annie, who lived just a few hundred yards from the most common areas to view the NHO. She walked over one day to see what the brouhaha was about. After looking through someone’s powerful viewing scope and REALLY seeing him she exclaimed, “I am not even a birder, but this is pretty exciting.” I met another nice couple from Connecticut, they had driven up through treacherous icy roads and fog to catch a glimpse of what for many is a “life bird.” One day I had a cement truck quickly slow down and veer into the parking area as I was walking from my car to take up my normal viewing spot. The driver jumped out and ran up to me. He explained that he drove by this spot each day and wondered what was going on. I explained, and with his curiosity quenched, he thanked me hopped back in his truck, and drove off with a satisfied look.

As I stood by the road with the tripod and large lens I was an easy beacon helping many a pilgrim find their quarry. A surprising number mentioned that they had seen me along the road a previous day and decided this time to stop and look. Some say that regifting is not polite, but in this case, I took great pleasure in helping others, even if inadvertently, share in this wonderful offering from the north.

Happy Holidays!

P.S.

I recommend opening the image up to full size to really see how beautiful he is….make use of that big monitor if you have it.

30

Shot of the Month – November 2013

Check out Vanessa, isn’t she lovely? Actually, it could be a he, I have no way of knowing, but either way, it definitely is a Vanessa. Perhaps a full introduction is in order. Please meet Vanessa cardui, her more formal, scientific name.

Check out Vanessa, isn’t she lovely? Actually, it could be a he, I have no way of knowing, but either way, it definitely is a Vanessa. Perhaps a full introduction is in order. Please meet Vanessa cardui, her more formal, scientific name.

There is a pretty good chance that you have met “her” before as this is one of the most common butterflies in the world and is found on every continent except Antarctica.

In less formal settings Vanessa is known as The Painted Lady. In some circles, mainly in Europe, her nickname is the “Cosmopolitan” highlighting her global distribution.

In my image to the left, we see the underside of the Painted Lady’s wings. In butterfly lingo, this is the ventral side of the wing. The ventral side is seen when the wings are closed. When the wings are open we are looking at the dorsal side.

Dorsal = open wings

Ventral = closed wings

On the ventral side, the wings have a fascinating camouflage pattern and have 4 colored eye spots. The eye spots and the pattern markings on the hindwings are designed to draw predators’ attention away from the butterfly’s head.

With wings open, as shown to the right, Vanessa is draped in orange with black and white highlights. (source)

With wings open, as shown to the right, Vanessa is draped in orange with black and white highlights. (source)

Alas, such beauty is fleeting.

The life cycle of the Painted Lady is typically 2-4 weeks! In warmer climates, they can live longer but rarely do they survive beyond one winter.

Painted Ladies are very popular in elementary schools where students can observe the entire “circle of life” firsthand. Butterflies go through 4 distinct stages of life:

Egg: 3-5 days

Larva(Caterpillar): 5-10 days

Chrysalis: 7-10 days

Butterfly: 2 weeks

Here is a nice graphic showing the life cycle.

Moral of the Story: Life is short, get out there and do your part to make it beautiful.

Thanks, Vanessa…

31

Shot of the Month – October 2013

This month one of the most readily recognizable and popular birds in the United States. How popular? Well, no less than seven states have made this species their state bird (North Carolina, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Virginia). And then there are the sports teams. This bird is a very popular mascot — a certain St. Louis baseball team uses this bird as their moniker, as does an NFL football team in Arizona. Many a high school, college, and university fly this bird’s likeness on their team flag.

This month one of the most readily recognizable and popular birds in the United States. How popular? Well, no less than seven states have made this species their state bird (North Carolina, West Virginia, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Virginia). And then there are the sports teams. This bird is a very popular mascot — a certain St. Louis baseball team uses this bird as their moniker, as does an NFL football team in Arizona. Many a high school, college, and university fly this bird’s likeness on their team flag.

Still in doubt? (you non-birder, non-sports fan, non-mid-west/Southerner types) Part of the problem might be that this photo is of the female gender of this bird species. Per usual, the male tends to garner all the attention.

Another clue, they are named after these guys:

No, it is not the monk bird.

Of course, it is a Cardinal.

To be accurate, it is a Northern Cardinal (NC). For you bird geeks out there, the term cardinal includes about 60 species of birds (see the whole list here) that us laypeople would call tanagers, grosbeaks, buntings, chats, and saltators that may exhibit a broad range of colors from red to blue to green to just about any color in the rainbow.

To the right is the flashy male Northern Cardinal that is almost universally recognized, even by non-bird enthusiasts:

No doubt that the male is a stunner, a startling all-out attack of RED; the female is more subtle, with delicate tones of tan and caramel with well-appointed red highlights.

A few bird bits to ponder:

- Northern Cardinals used to be found primarily in southern states. With the proliferation of bird feeders and warming climates, these birds can now be increasingly found from Mexico to Canada, from Maine to Nebraska.

- NCs are ground feeders and dine mostly on seeds (hence that powerful, seed-cracking beak).

- NCs used to be popular pets but the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 put an end to that silly practice. If you capture or kill a NC you can be fined $15,000.

- Cardinals mate for life. The females really dig the red — the brighter the male plumage, the better the success in finding a mate.

- NCs don’t migrate.

- Unlike many other songbirds in North America, both the male and female can sing. Usually, only the male sings.

Next time you spot that glorious jolt of red at the feeder or in the woods, take a bit of time to find and appreciate his lovely partner…

Until next month….:-)

30

Shot of the Month – September 2013

In my current state of being (geographic, not metaphysic), Vermont, September is the month when the trees explode with color. I found this scene during a short walk down the mountain road that we live on. I like how there is a spiral of color on the outside that guides you to the forest within that seems intent on resisting the change of seasons.

In my current state of being (geographic, not metaphysic), Vermont, September is the month when the trees explode with color. I found this scene during a short walk down the mountain road that we live on. I like how there is a spiral of color on the outside that guides you to the forest within that seems intent on resisting the change of seasons.

How and why do leaves change their color? I forgot long ago. As a service to all those who also forgot their 5th-grade science here is a simplified summary:

Leaves create the food trees need to survive by converting light energy into chemical energy that is used to convert water and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates (sugars). These sugars are the fuel for a plant’s growth and maintenance.

Leaves contain several pigments, chlorophyll, and carotenoids, to absorb different wavelengths of light to facilitate photosynthesis. Chlorophyll captures red and blue wavelength light but reflects green light — that is why most plants are green. Carotenoids (also found in corn, carrots, and bananas) increase the efficiency of photosynthesis by expanding the spectrum of light captured by the leaf. Carotenoids capture blue and green light and reflect back yellow and orange. Leaves always contain yellow and orange pigments but we can’t see them in the summer due to the dominance of chlorophyll.

In the fall trees begin to produce less chlorophyll as they begin to shut down food production. As the green chlorophyll fades from the leaves the carotenoids are finally revealed in all their glory.

Ok, so we have covered the different shades of yellow and orange found in the autumn palette, but what about the reds? Ahh yes, the glorious reds.

The red pigment (including pinks and purples) in leaves is produced by anthocyanins (also found in cranberries, cherries, strawberries, and plums). This pigment is not present in leaves until the fall and the production of this pigment varies greatly depending on the weather. Surprisingly (at least to me) scientists are not exactly sure of the role of anthocyanins — the leading theory is that the red pigment protects the leaves from the sun giving them extra time to transfer nutrients from the leaves into the twigs and roots before the arrival of winter.

Yellow, gold, and orange colors remain constant from year to year as carotenoids are always present in leaves and the amount does not change in response to weather. The intensity of red can vary greatly from one year to the next. The best autumn colors are produced when there is a:

- Warm, wet spring; plus

- A summer that is not too hot or dry; plus

- A fall with plenty of warm sunny days and cool nights (below 45 F but above freezing)

Who knew chemistry could be so beautiful?

Want to learn more?

Why are plants green? (a nice video)

Light absorption for photosynthesis (geeky physics with colorful graphs)