30

Shot of the Month – June 2015

Let me tell you, getting a decent picture of a Painted Turtle is tough. This is not to say that they are hard to find — they are by far the most commonly found turtle in North America.

Let me tell you, getting a decent picture of a Painted Turtle is tough. This is not to say that they are hard to find — they are by far the most commonly found turtle in North America.

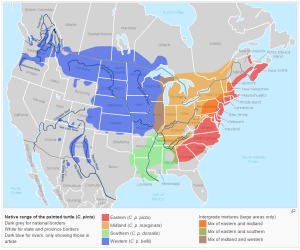

They are the only turtle whose native range extends from the Atlantic to the Pacific. These guys can be found in 45 US states and 8 of the 10 Canadian provinces.

As a photographer, the challenge is that the painted turtle is most commonly seen basking in the sun in the late morning. This makes for terrible light and harsh reflections off this shiny creature. Also, these turtles are very skittish so it is very hard to get close before they dive into the water. The joys of nature photography ….grumble, grumble…

There are four regionally based sub-species of painted turtle (eastern, midland, southern, western), with each having slightly different color patterns and size. I photographed this Midland Painted Turtle on a quiet pond in Vermont. Check out the map below to see which type may live near you (Only for you New World types).

Painted turtles like fresh water so if you have visited a pond, lake, marsh, or creek in the US or Canada you most likely have seen one of these fellas.

This is one rock ‘n roll-looking turtle — note the KISS-themed red and yellow stripes on their neck, legs, and tail. And that bad-ass black stripe on the yellow eye. Did you notice the claws on this turtle?! Wolverine has nothing on this guy.

All right, settle down. Back to the science. A few other painted turtle tidbits for you:

- Painted turtles can live up to 55 years in the wild. (they rarely do, but they can)

- Females are larger than males. The extra size allows space for egg production.

- In the winter painted turtles hibernate in mud at the bottom of the body of water where they live. They lower their metabolism so much that they do not need to breathe while in this state. In northern climates, they may hibernate from October to March (Now, THAT is a good nap). Turtles also sleep at the bottom of the water each night — during these periods they can absorb some oxygen through their skin.

- Painted turtles eat assorted plants (e.g. duckweed, algae, and water lilies) and also eat earthworms, insects, leeches, snails, crayfish, frogs, and carrion, to name a few delicacies.

- As they are reptiles painted turtles cannot regulate their body heat. To be active their body temperature has to be between 63-73 degrees F. Each day they go through cycles of activity. First, bask in the sun and build up energy. Then go into the water and hunt for something to eat. Being underwater cools them down, so, bask in the sun again. Once warm, go search for food. Cool off. Bask in the sun. Search for food. You get the idea.

- Painted turtles are the “Official Reptile” of four states: Vermont, Michigan, Illinois, and Colorado. I didn’t even know that was a thing.

There you have it, the painted turtle — Mother Nature’s Rock ‘n Roll playing Marvel Comic Superhero who can be readily found chill’n at your local pond. Until next month…

Nikon D300S, Nikon 200-400mm (@ 260 mm; effective 390mm), f/4, 1/2000 s, ISO 400; handheld from Kayak

30

Shot of the Month – May 2015

Warning: There may be a bit too much “inside baseball” chatter in this month’s post but stay with me if you can. Or at least, do stop long enough to enjoy the pretty picture.

Warning: There may be a bit too much “inside baseball” chatter in this month’s post but stay with me if you can. Or at least, do stop long enough to enjoy the pretty picture.

As a child, I grew up as a big fan of Baltimore Orioles. My brother and I shared a room and though we rarely agreed on how that space should be apportioned, we both reveled in having a poster of Brooks Robinson on the wall. At this time Boog Powell was a household name as was Frank Robinson and Jim Palmer. Now, if you are a bird lover, but not a baseball fan, not over the age of 50, nor grew up within a hundred miles of Baltimore, you are probably thoroughly confused. And quickly getting bored…

You see I grew up but a mere one-hour drive from the city of Baltimore, Maryland, the home of the Baltimore Orioles baseball team. And it just so happens that their golden era coincided with my youth as they won the World Series in 1966 and 1970. Brooks (3rd base), Boog (1st base), Frank (outfield), and Jim (pitcher) were the all-stars of those glory years.

The only oriole I ever knew of was this guy to the right. (His looks have changed a bit over the years.)

Oddly, for most of my life I never really thought about what the real version of the mascot actually looked like. I had no idea where they lived. I had never seen one even though they are pretty common throughout eastern United States in the summer. I had to come all the way to Vermont to see my first real-life oriole. And the guy in my photo was a particular treat in that he stopped by for a few days just outside our window during the spring last year. We live near the top of a mountain and we hadn’t seen an oriole at such an altitude before — nor since.

The bird and the city are both named after George Calvert. Hang on, I am getting there. George was also known as Lord Baltimore (ahhh…) and he helped colonize what is now Maryland. Ok, that explains the city’s name, but what gives for the bird? The coat of arms for the Calvert family contained a similar color pattern as our avian friend so ye olde bird guys chose that moniker for da bird. The coat of arms shown here is actually for Cecil Calvert, George’s son, but you get the idea. If you know the state flag of Maryland, the coat of arms will look pretty familiar.

Wanna take a guess at the state bird of Maryland?

If you live in the right zip code do yourself a favor and go find a Baltimore Oriole — it is a real visual treat. They can be hard to find however as they tend to hang out at the top of trees. But catch a male in the afternoon light, against a blue sky and his orange chest will beacon like a burning torch — it is stunning to behold. Get out there, you deserve it, hon.

Until next month…m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 560

30

Shot of the Month – April 2015

This month a landscape photo captured on a lovely fall afternoon in Yellowstone National Park.

I originally chose this image as a shot of the month because I think it’s purty (IMHO). I like the vast range of colors, shapes, and textures. And I like the transition from full-bore color and texture in the foreground with the dense collection of shrubs, bushes, and sundry plant-like things, to less color and density as you gaze past the tree to the more open fields. To the hillside with only a few colors, green and black mainly. Leading to a hilltop that is denuded and virtually monochromatic till you reach an essentially white sky.

However, the more I stared at the image I realized that the visual depth of this image hinted at the depth of connection between the animals, the plants, and even the forces of nature like fire, wind, water, and so on that co-exist in this landscape. This was more than just a pretty picture.

Let’s start with those denuded trees at the top of the hills behind the tree — that part of the forest was ravaged by fire and the trees have died. Don’t be alarmed, this is a glorious thing. For the first 100 years of the park’s existence, the rangers would extinguish forest fires thinking they were protecting this great park. Rangers eventually realized that fire plays an essential role in revitalizing the park’s ecosystem and they now allow fires to burn naturally and will even instigate controlled fires to mimic natural processes. Fire reduces dead vegetation, stimulates new growth, and improves habitat for wildlife. Soil samples from the park reveal that fire has helped shape and nurture the landscape in this area for over 14,000 years.

“Ugh – Fire Good.” (Said in my best caveman voice)

And then there is that gnarly cottonwood tree in the foreground. Cottonwoods are few and far between these days in Yellowstone, much like the Aspen and the Willow trees. These trees went into rapid decline after the last wolves were killed in Yellowstone in 1926. What do wolves have to do with trees? Well, with the top predator gone the elk population exploded and young trees and saplings were overgrazed and could not recover. Since the reintroduction of wolves in the park in 1995 the trees appear to be making a comeback. Astoundingly, the wolves seem to touch virtually every life form in the ecosystem. Watch this video:

Now when I see this image I don’t see just a few trees and shrubs, but the entire park and its entire history. Every element in this photo exists, or doesn’t because of every action or inaction that took place to arrive at this day. That cottonwood tree may be standing there because of a wolf that was born in 1996 and the life she led.

Everything we do, or don’t do, has an impact on life, big and small, even when out of sight.

with Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

Until next month…

Nikon D4S, Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 VRII @95mm, f/8, 1/125s, ISO 200, +0.5 EV

30

Shot of the Month – March 2015

Much of my photography reflects my bias towards warm hues and vibrant colors. I am on record for preferring to photograph brightly colored birds over those draped in shades of brown.

Color photography shows a world that we are most familiar with as most humans see the world in color. Color images can evoke a range of emotions as broad as the spectrum of a rainbow.

That being said, some of the most powerful images ever captured are black and white (B&W), and much “fine art” photography is sans color.

For me, an image is about telling a story. Strong use of color can tell a great story. However, color can also be a great distraction. B&W images remove that distraction and allow the viewer to explore the world in a new way.

Removing the color from a shot changes the focus—it shifts the viewer’s attention from the colors to things that can be more abstract, less immediately noticeable, and it presents the world to us in a way that few of us are used to seeing it. It can, by the very removal of that familiar element, generate an intense amount of interest and a powerful feeling of drama that might otherwise be overwhelmed by the presence of the color. (Source)

In the original color image, I found the green bushes to be a distraction and the sharp color divide made the photo feel disjointed. Once I converted to B&W the photo seemed to be more visually coherent. And now the image was less about reporting what I saw, a moose in a rain shower, and became more universal in embodying mood and perhaps melancholy.

Some photographers are drawn to shoot in black and white because creating a compelling image without colors requires a strong understanding and mastery of the visual building blocks of a great photo: texture, tonal contrast, shape, form, and lighting.

A few pointers on making a worthy B&W image:

- Visualize in B&W but shoot in color. Yes, really. Best to shoot in color first and then convert later. You will have more data and options to work with.

- To visualize in black and white only pay attention to lines, shadows, and shapes.

- Look for contrast. Strong B&W photos usually have strong whites and deep blacks.

- Look for texture. (Think old barns and how great they look in B&W)

Learning to see the world in B&W will allow you to exercise a different set of visual muscles and will make your “colorful” stories even stronger.

Here is a good article on how to see in black and white.

Until next month….m

Nikon D200, Nikon 70-200mm f/2.8 VR (@110mm), 1/125 s, f/16, ISO 400

28

Shot of the Month – February 2015

Here you go, a shot that best captures the essence of February. Blank stare from reader…

Come on, what is February famous for? For one thing, it has Valentine’s Day, which at least in modern times is all about the celebration of love and companionship (and the commercialization of love and massive consumption of chocolate, greeting cards, roses, etc., but let’s not go there). Look at this adorable set of lovestruck whistle pigs as they nuzzle side by side and gaze out across the tracks during a late afternoon stroll – that’s as Hallmark moment as it gets.

What else is this month famous for (in a US-centric kind of way)? Yes, each February 2nd we pull some poor groundhog out of its den to determine if we will get six more weeks of winter. The aforementioned whistle pigs are groundhogs. Other aliases include woodchucks, ground beaver, and mouse bear. What’s with all the crazy names?

Chucked wood? Ironically, these two lived in this wood pile. Disclaimer: No wood was chucked in the making of this image.

Woodchuck: Has nothing to do with wood, or chucking. The Algonquian name for the creature is wuchak. Which leads to one of my favorite tongue twisters.

How much wood would a woodchuck chuck

if a woodchuck could chuck wood?

A woodchuck would chuck all the wood he could

if a woodchuck could chuck wood.

Whistle pig: Groundhogs thrive in open areas and will often sit on their back legs or stand to watch out for danger. If they see a threat, usually in the form of a wolf, cougar, coyote, fox, bobcat, bear, eagle, or dog, they let out a whistle to warn the neighbors.

Mouse bear: They look like miniature bears when sitting upright.

Groundhogs are one of the few animals that truly hibernate in the winter and can go 150 days without eating. They only lose about 1/4 of their body weight during this period as they are so adept at slowing down their metabolism as they sleep. Groundhogs come out of hibernation in March and mating season begins in early spring. Male groundhogs will rouse themselves from their sleep in early February however to wander about their 2-3 acre territory in search of a den with a female. The male will enter a female’s den and spend the night. No mating, just a visit to get to know each other better and smooth the way for a successful March. If you get my drift. (source)

Romance, whistle pigs, and February — a match made in Heaven.

Until next month….m

Nikon D4s, Nikon 600mm, f/5.6, 1/500s, ISO 800, -0.5 EV

31

Shot of the Month – January 2015

This month an image of one of Florida’s marquee birds. Now if you are not paying close attention you might think this is a shot of Florida’s renowned pink flamingo. Wading bird – Check. Pink plumage – Check. Florida – Check. But the giveaway that this is not a flamingo is in the bill. Check out the big spatula on Brad (pop culture reference). What we got here is a Roseate Spoonbill — Florida’s other pink bird.

This month an image of one of Florida’s marquee birds. Now if you are not paying close attention you might think this is a shot of Florida’s renowned pink flamingo. Wading bird – Check. Pink plumage – Check. Florida – Check. But the giveaway that this is not a flamingo is in the bill. Check out the big spatula on Brad (pop culture reference). What we got here is a Roseate Spoonbill — Florida’s other pink bird.

Myth Buster Alert: I, like most Americans I imagine, associate flamingos with Florida. Turns out that the American Flamingo does not breed in Florida and the occasional sighting is most likely that of a bird that escaped from captivity. In lower Florida, in the southern reaches of the Everglades, you may see a flamingo that is a vagrant from the Yucatan Peninsula. When Europeans first discovered Florida there was a small breeding population but that population either died off or migrated to other locations further south. So, despite all the flamingos in the souvenir shops, flamingos are not really part of Florida’s natural landscape. Wow, mind officially blown. (source)

But we are here to talk about a true Floridian — the Roseate Spoonbill. There are six species of spoonbill around the world and the Roseate is the only one that is pink. And it is the only one found in the Western Hemisphere. Roseate Spoonbills are typically found in Central and South America as far south as Argentina and Chile. They can also be found in the Bahamas, the Caribbean, and Cuba. In the US the breeding range is limited to coastal Texas, southwestern Louisiana, and Southern Florida. A popular place to see the Roseate Spoonbill is in Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge where I photographed this fellow.

The Roseate Spoonbill uses that signature bill to good use — it is a very effective tool for catching dinner. In the early morning and late afternoon the spoonbill can typically be seen wading through shallow water, head down, as it sweeps its bill from side to side near the bottom of the water with its mandibles slightly open. The bill has very sensitive nerves and will snap shut rapidly if prey is felt. Notice the two narrow slits near the top of the bill? They allow the bird to continue breathing even while the bill is submerged looking for prey. Pretty smart. Minnows comprise 85% of the spoonbill’s diet though they also eat shrimp, mollusks, frogs, newts, and some types of aquatic plants. Like flamingos, the spoonbill gets its pink color from the algae that is found in the crustaceans that the bird consumes.

Florida was almost left completely pink-free in the 1800s as the population was decimated by professional plume hunters to make hats and fans for stylish ladies of that era. By 1930 only 30-40 breeding pairs remained. Fortunately, action was taken and hunting of the bird was banned and special conservation areas were created to protect the bird. Since then the population has rebounded and about a thousand breeding pairs live in Florida. Today the main threat to the spoonbill is the loss of habitat as Florida continues to expand human settlements into coastal areas where spoonbills typically live.

Well, at least for the moment it is great news that the Roseate Spoonbill is literally, and figuratively, “in the pink.” (collective groan)

Until next month….m

Shot Information:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm w/ 1.4 x TC (effective 850 mm), f/5.6, 1/750s, ISO 200,

31

Shot of the Month – December 2014

The Pronghorn is a one-of-a-kind, American original. Though we sometimes call it the “Pronghorn Antelope” or “American Antelope,” and despite his looks, the Pronghorn is not an antelope. Pronghorns are the only surviving member of its family (Antilocapridae) and has no close relatives on this continent or any other. In case you were wondering, there are no antelopes in the New World.

The defining characteristic of the Pronghorn is its speed — it is the fastest land mammal in North America. We all know that the fastest animal in the world is the cheetah (see my write-up here). While difficult to measure the cheetah may be able to reach speeds up to 75 mph. The top speed for the Pronghorn is believed to top out around 53 mph. However, one could make an argument that the Pronghorn is the fastest animal alive. How so? Well, the cheetah can only maintain his top speed for a few hundred yards while the Pronghorn can reach 53 mph for a few hundred yards but then cruise at 30 mph for miles and miles. And miles. No other land mammal can keep up with the Pronghorn over a long distance.

The speedy nature of the Pronghorn is a bit of a mystery as none of its current predators, cougars, wolves, coyotes, or bobcats can run that fast. Some scientists posit that Pronghorns developed their speed in response to now-extinct predators like the American cheetah.

In the fall of 2014, I visited Yellowstone NP and spent some time among a herd of Pronghorn during the rut. I was able to see up close the explosive speed of the Pronghorn male as he would chase off rivals or corral errant females. I wanted to try and make an image that would convey the speed of the Pronghorn. Ironically, to demonstrate speed, the trick is to slow the camera down. I normally obsess about ensuring that I use proper technique and camera settings to allow for the sharpest images possible. For this image, I had to fight all my instincts and lower my shutter speeds to allow blur into the photo. I normally shoot with a shutter speed near 1/1000 of a second to stop the action and ensure razor sharpness; for this image, the shutter speed was 1/30 of a second. The key is to pan the camera at the same speed as the subject to try and keep it at least partially in focus while the background blurs with the motion. I experimented with shutter speeds of 1/15s, 1/30s, 1/45s, 1/60s, 1/90s, and 1/125s. The slower the shutter speed the more dramatic the effect. And all the harder to get something pleasing.

A few examples of how shutter speed can change the look of the image:

Here the shutter speed was 1/500s. Fast enough to completely stop the running Pronghorn. It is a decent photo but the image is oddly static given that it is a picture of a running animal.

Here the shutter speed was 1/125s. A bit of background blur is introduced while the Pronghorn is still quite sharp. Starting to get a sense of motion.

A shutter speed of 1/45s was used for this shot. More blur with the background and now the legs are starting to blur.

Here a shutter speed of 1/15s. The image is becoming more abstract.

I had a blast experimenting with the new approach and exploring new ways to communicate the story I was trying to tell. So, which image do you like best?

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm w/ 1.4x TC (850mm), 1/30s, f/11, ISO 200, +0.5 EV

30

Shot of the Month – November 2014

Course Title: Photography 101

Lecture #1: Composition

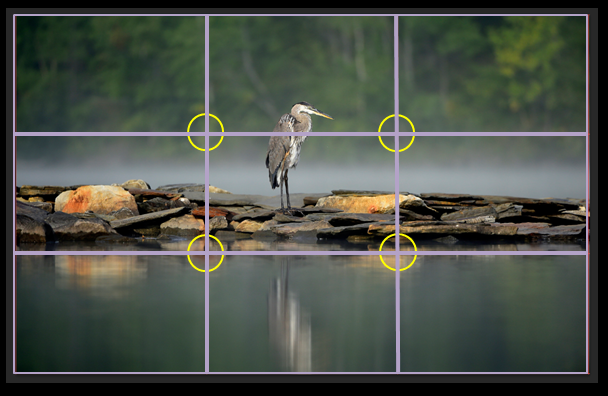

Rule #1: Never put your subject in the center of the image. (Yes, this will be on the final)

Ooops.

In the above photo I have broken a cardinal rule of photography composition — don’t put the subject of your photo in the center of the frame. Generally, photos with a dead-center subject tend to look too static, boring, dull — in a word, dead. I once read an article where the author recommended sticking a piece of masking tape in the center of the LCD screen on the back of your camera to make it hard to make that common error. It would look something like this:

It is generally recommended that you follow “The Rule of Thirds” (cue harp music). How does that work? Well, imagine two horizontal lines that divide your image into three equal parts. Next, add two vertical lines that break the image up into three equal parts. In the case of my photo, it would look like this:

To follow the rule of thirds you would align your subject along one of those four lines or at the intersection of those lines (shown by the yellow circles). If you are not sure how to compose the scene before you, start with the rule of thirds. Most cameras have a grid built into their display (check your manual folks) that you can turn on to help with composition.

To follow the rule of thirds you would align your subject along one of those four lines or at the intersection of those lines (shown by the yellow circles). If you are not sure how to compose the scene before you, start with the rule of thirds. Most cameras have a grid built into their display (check your manual folks) that you can turn on to help with composition.

I photographed the Blue Heron above from a kayak in Vermont over the summer. I took a variety of images, some closer, some further, some with the heron centered, others with him off to the left, then to the right. I oriented some in landscape and others in portrait. I really liked the color and texture of that narrow band of rocks and this centered composition allows the rocks to be the dominant element. For this scene, I think the symmetry works.

I have a similar image where I more closely followed the rule of thirds. But with that compositional change, I find that the heron becomes the dominant subject. A pleasing image, I think, but it tells a different story.

If we always followed the rules, life would be kinda boring, wouldn’t it? And all of our photos would look the same. Of course, there are no rules. A professional photographer told me once, “The only rule is that if it looks good, shoot it.”

Now that’s a rule I can live by.

Here is a fun video explaining the rule of thirds.

Until next month….michael

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm f/4 (@400mm), f/5.6, 1/1000, ISO 400

31

Shot of the Month – October 2014

I highly recommend that you check out the bugle concert series held in Yellowstone National Park each fall. To be honest, the music is really just so-so — the event is more operatic than philharmonic. But you will be spellbound just the same.

As the dawn sun fights its way up, through the chilled air the mountains surrounding us slowly ignite with color. Laden with tripods, cameras, and lenses we clamber over hill and dale in search of the best balcony seats to catch the show. We wonder when, even if, the event might start as we drive our hands deep into our coats to fight off the cold.

And then, at the edge of the sky, the silhouette of a 700-pound bull elk blocks out the light.

Dramatic entrance indeed. The melee begins.

Standing five feet at the shoulder, with another four feet and forty pounds of antlers the rogue towers over 9 feet tall. Wide-eyed, he thrusts his chest forward as he peers down on the hills and valley below. His body is an endless twitch as testosterone courses through him. The chemical transforms him into a maniacally focused beast. He is driven to conquer his rivals and win the right to pass on his genes.

The elk rut has begun. Each day over the next 4-6 weeks he will repeatedly bugle, unleashing a loud, screech of a wail to attract female herds and warn off other male suitors. It can be heard for miles.

During this period the bull will eat little, bugle often, and continually……endlessly…..relentlessly chase and test cows for their readiness to mate. Cow elks only come into estrus for 1-2 days so the male must be ever diligent. In a word — obsessive.

The dominant bulls will protect a harem of up to 20 cows from competing males and predators. When necessary, the bulls will fight. Rivals bugle at each other. If both are of similar size they approach.

Males may walk in parallel sizing each other up while trying to intimidate. If neither backs down then they lock antlers and wrastle it out. These fights are rarely fatal but they take their toll.

The bulls are frenetic, rarely relaxing even for a moment. Constantly watching over the herd. Endlessly chasing and scolding cows that dare wander too far. Warding off lesser males. I was exhausted just watching. During the rut, a bull can lose 20% of his body weight. After such a tremendous effort some bulls will not recover in time and will perish during the winter.

For two fortnights, the continual call to arms leaves some victorious, others vanquished. And for this observer, it left a memory made up of surely more than just sound, but also fury, firmly etched into my being.

The below video, shot in the Rocky Mountain National Park, gives a sense of the bugle boys in action.

Nikon D4S, Nikkor 600mm, 1.4x TC, (850 mm) f/5.6, 1/750 s, ISO 400, +0.5EV

25

Shot of the Month – September 2014

The Common Loon is the epitome of style and grace — most of the time. Loons spend most of their time on water and their bodies are exquisitely designed to make them powerful and effective swimmers and divers. Most birds have hollow bones while loon bones are solid. This extra weight enables loons to dive to depths of 250 feet in search of fish – the mainstay of their diet. They have large, powerful feet that propel the bird through the water like a torpedo. The bird’s feet are located unusually far back on the body which enable powerful underwater thrusts (imagine the avian version of Michael Phelps and his size 14 feet ). In the air loons are regal athletes that can fly hundreds of miles and reach speeds of more than 70 mph.

Now for some of those less stylish moments in loon life.

Loons have a very difficult time walking on land given the placement of their feet on their bodies. In fact, the name, “loon” most likely comes from either the Old English word lumme, meaning lummox or awkward person, or from the Scandinavian word lum, meaning lame or clumsy. Both of these names refer specifically to how loons look when hoofing it on land. To avoid such embarrassment loons rarely venture on terra firma except to nest and even then their nests are usually found only a few feet from the water’s edge to make for a short commute.

And while loons are powerful flyers they have a bit of a struggle in the transition up and down. Loons are unable to take off from land and on the water they need a long distance as they run across the surface building up momentum. Loons need anywhere from 30 yards to a quarter-mile of running and flapping before liftoff. In my photo above you can see those large feet in full force as he runs for the sky. The need for such space for takeoff means that you will never find a loon in a very small pond or lake as they do not provide enough of a runway for Loony Airlines.

And then there is the landing. Oh boy. Again, as the feet are so far backward loons are unable to land feet first like your typical bird. When they land on water they fly in head first and skim along on their bellies until they slow down. It is a sight to behold.

Incoming……. ……Outgoing

In their formal black and white dress and powerful moves, the common loon has a James Bond mystique. I have to admit a certain schadenfreude in knowing that these superstars also have their Mr. Bean moments like the rest of us.

Until next month…

Exposure:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm f/4 (@400mm), f/4.8, 1/1000 s, -0.5 EV, ISO 400