28

Shot of the Month – February 2017

This month we visit with the natural world’s “Unbreakable” star – the coyote. I photographed this fine-looking fellow in Yellowstone NP. For the uninitiated, the film “Unbreakable” is an American film about a man who learns that he has supernatural powers and basically, he can’t be killed. The Coyote, at least as a species, seems to have similar powers. (I recommend the film, if you haven’t seen it)

In the last two hundred years we have done a wonderful job of wiping out many of the continent’s top mammals. Fifty million bison were reduced to about twelve thousand. The grey wolf used to inhabit the entire United States but is now largely extinct from most of the country. The North American cougar was extirpated in the eastern half of the country by the beginning of the 20th century.

And we have been working overtime to kill off the coyote. We kill a coyote every minute in the United States. I’ll repeat that morsel, in case you blinked.

We kill a coyote every minute in the United States. In other words, we kill about 500,000 coyotes each year.

Coyote Killing Contest (Source)

We are very determined to wipe this animal out. In the 1920s the US government created the Eradication Methods Laboratory whose sole job was to kill predators that we didn’t like. Congress passed a bill in 1931 allocating $10 million to the lab to launch a poison campaign. From 1947 to 1965 the agency killed about 7 million coyotes using blanket poisoning, sometimes putting out up to 4 million poison baits at a time. Since the 1970s this job was handed over to the Wildlife Services Agency, which is part of the Department of Interior. Since 2000 the agency has killed 2 million mammals (coyotes, wolves, and cougars) and 15 million birds. More recently the government uses airplanes to shoot about 80,000 coyotes per year on behalf of the livestock industry. Many states have a bounty on coyotes and you can pretty much kill coyotes at will in many places. In some states, they have contests to see who can kill the most coyotes in one day.

Normally, this is the part where I tell you how dire the situation is for the coyote. How they are highly endangered and near extinction. Not this time, my friends. As I mentioned, the coyote is unbreakable.

In fact, the coyote is THRIVING. Never been better, thanks for asking!

How is that possible??!!

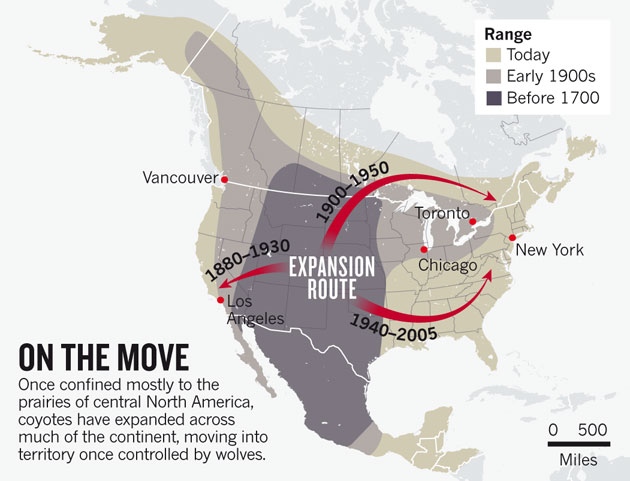

The coyote’s superpower is adaptability. They are masters of exploiting the changes in the environment caused by humans. When the settlers arrived coyotes only lived on the western plains but once we killed off the wolves everywhere else the coyotes began to migrate into new territories and they now occupy most of the continent.

Coyotes historically were smaller than wolves and couldn’t compete with them. In the 1800’s the wolf population was at a low density due to human persecution and wolves had a difficult time finding a mate. As coyotes migrated east the wolves took the next best option and mated with their smaller “cousin”. As a result, the northeastern coyote-wolf hybrids were bigger, stronger, and able to kill larger game. This allowed coyotes in the east to be able to kill deer, something their smaller relatives in the west are unable to do.

Coyotes have also moved into urban centers and seem to love life in New York City, Washington D.C., Chicago, and Los Angeles, to name a few of their favorite haunts. Turns out that cities are pretty safe because people are not shooting, trapping, or poisoning them there. The coyotes adapted their diet to eat squirrels, household pets and discarded fast food. In rural America coyotes live for about 2 to 3 years while in the city a coyote can live for 12 to 13 years!

Under normal conditions, coyotes have 5-6 pups in a litter. However, when the coyotes feel persecuted they increase their litter size to 12 to 16 pups. You can kill off 70% of coyotes one year, but by the next summer, their numbers will have recovered. They use howls and yipping to create a kind of census of the coyote population. If their howls are not answered by other packs, it triggers an autogenic response that produces larger litters. (Source)

Coyotes also developed a fission-fissure adaption to help them survive. If life is going well, coyotes will live and hunt in packs. However, if they are persecuted, say by wolves or humans, then coyotes will abandon pack life and scatter across the landscape in singles or pairs. For example, the poison campaign of the 1970s really helped scatter coyotes across the country.

There you have it, another sad tale that makes me embarrassed and ashamed to be a human. But congrats to the coyote for stickin’ it to the man. I’m rooting for ya!

Check out Project Coyote to learn how you can get involved to stop the slaughter of coyotes and MANY other animals.

For more outrage, click here:

National Geographic article on the Wildlife Services Agency

Washington Post article on the Wildlife Services Agency

I got much of my information for this post from these great articles. Highly recommended:

How the Most Hated Animal in America Outwitted Us All (National Geographic article)

Rise of the coyote: The new top dog (Nature Journal article)

Until next month…..

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm f/4 lens @ f/8, 1/2000 s, ISO 400, EV +0.667

31

Shot of the Month – January 2017

As you may recall from an earlier post, I am a BIG fan of owls so it is an exciting day when I get to add a new owl species to my portfolio. Let me introduce the Short-eared Owl (SEO), as captured here in this lovely winter scene that I found about an hour north of Seattle. Upon moving to Washington State I learned that Short-eared Owls (SEOs) winter over in my new state to escape the cold of northern Canada. Accordingly, I have been spending many a chilly weekend out looking for these aerial acrobats.

Owls can be very hard to photograph as they are usually most active at night. SEOs are one of the easier owls to view, relatively speaking, in that they often hunt during the day. Bless them.

The Short-eared Owl prefers open terrain and can be found in prairies, coastal grasslands, meadows, savannas, tundra, marshes, and other low-vegetation habitats.

These owls specialize in hunting voles and other rodents. The owl usually flies just a few feet off the ground as it scans for a meal — its flight can be highly erratic

and undulating. As it listens and looks for prey it may suddenly bank to one side or another, or slam on its air brakes to drop to the ground feet first to grab its victim. Sometimes it will hover over a spot as it waits for an opportunity to pounce.

Imagine a large moth flying over a field and you will have a sense of its herky-jerky flying style. As a photographer, I can tell you that trying to capture an image of an SEO in flight is one of the most difficult types of photography I have tried to do. I will be tracking it, tracking it, just about ready to release the shutter, and then, poof, the bird vanishes from the viewfinder. This happens A LOT.

On a typical day, I will arrive at sunrise and take up a position in the field. And then I wait. As the sun rises, and the voles and mice become more active, the SEOs suddenly appear from the ether. I have seen as many as seven SEOs working a large field at the same time. The owls crisscross their way over the terrain in sortie after sortie as they look for prey. It is an amazing scene to behold though it must be a rather terrifying experience if you are a vole.

On a typical day, I will arrive at sunrise and take up a position in the field. And then I wait. As the sun rises, and the voles and mice become more active, the SEOs suddenly appear from the ether. I have seen as many as seven SEOs working a large field at the same time. The owls crisscross their way over the terrain in sortie after sortie as they look for prey. It is an amazing scene to behold though it must be a rather terrifying experience if you are a vole.

The airspace above these fields will soon fall quiet as the owls begin to migrate back north for mating season which starts in March. I imagine that spring can’t come soon enough for the voles — a few months respite from the constant onslaught from those malevolent, murderous moths.

Until next month…

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm f/4, 1/1600 s, ISO 1600, +0.5 EV

31

Shot of the Month – December 2016

One look at this image and most of us shudder with cold in sympathy for this poor beast. Some might even clamor — “Help that poor animal, he must be freezing to death.” I am a real wimp when it comes to the cold and I normally walk around the house wearing multiple layers and a fleece — I seem to always be cold. So, upon seeing this bison in Yellowstone NP, standing in deep snow and generally covered in the white stuff, I felt quite despondent for him.

One look at this image and most of us shudder with cold in sympathy for this poor beast. Some might even clamor — “Help that poor animal, he must be freezing to death.” I am a real wimp when it comes to the cold and I normally walk around the house wearing multiple layers and a fleece — I seem to always be cold. So, upon seeing this bison in Yellowstone NP, standing in deep snow and generally covered in the white stuff, I felt quite despondent for him.

Well, dear friends, the nature science folks tell us that we can all relax. Bison have evolved over millions of years to deal with this type of weather. Our human concepts of what is cold simply don’t really apply in the bison world. When I photographed this bison I was standing in waist-deep snow and it was about 16° Fahrenheit. There was also a gusty wind that would swirl about causing mini blizzards every few minutes such that I would lose sight of this massive beast for a few seconds at a time. In Yellowstone, a temperature of 16° F is considered “moderate” — almost balmy conditions considering that temperatures can easily drop down to -30° F and beyond.

I have been told by park officials that bison don’t feel the cold until it reaches about -40° F. Nope, not a typo. In the winter a bison will grow a coat of woolly underfur with coarse guard hairs that protects them from the elements. This rich coat has 8 times the number of hair follicles compared to cattle. The fur is thickest on the bison’s head, on the front of their body and on their forelegs. When the wind blows us humans will often turn our backs to the wind to avoid the worst of it. Bison have no need for such contortions; given their full fur defense they are quite content to face directly into the onslaught. The bison swings its massive head into the snow to clear the way so that it can eat the grass that lies beneath — the body is so well insulated that the snow does not melt as you can see in this photo.

So, now you know, the next time you see what looks like a poor, freezing bison, you can rest assured that he is most likely doing just fine and is rather, just chillin.

Until next month….michael

🙂

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, 1.4 x TC (effective 850mm), f/9, 1/640 s, +1 EV, ISO 500

30

Shot of the Month – November 2016

For someone who doesn’t believe in climate change then karma would dictate that said person be reincarnated as a Pika. But before we get to the hot topic at hand, what the heck is a Pika you might ask. I think Pika is an acronym for Probably the most Incredibly Kute Animal. Though, I might be wrong on that.

The Pika is an incredibly cuddly and cute fur ball found amongst the highest mountain ecosystems around the world. “Fur ball” is pretty accurate as a Pika’s body is quite round and she doesn’t have a tail. There are about 30 species of Pika in the world (mainly Asia, North America, and parts of Eastern Europe) with one species found in the United States. The American Pika can be found in Colorado, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Nevada, California, and New Mexico. The fine lass (could be a chap, I have no way of knowing) above was photographed in Yellowstone NP.

The Pika is well adapted to surviving in alpine mountain ecosystems which are typically windswept, treeless, and frigid. The alpine zone only represents about 5 percent of the planet’s surface and thanks to climate change, this habitat is disappearing fast. As the mountain tops warm the vegetation changes, the snowpack melts and new predators and pests move in. Most mountain habitats in the Western US have warmed by at least 1 degree F in the last hundred years. In the next hundred years, the temperatures are expected to rise by another 4.5 to 14 degrees.

Pikas literally cannot take the heat. Expose a Pika to temperatures above 78 degrees and she will die within six hours. Yes, really.

In Oregon and Nevada Pikas have disappeared from 1/3 of their previously known habitat. Since the early 1900’s the Pika has disappeared from 8 of the 25 U.S. mountain ranges where they previously lived. Pikas keep climbing higher but once they reach the top of the mountains, they can’t go any higher to escape the deadly heat.

Expect to see the Pika on the Endangered Species list soon. And given current trends, the Pika may become the first known species in the US to go extinct from climate change.

As they say, karma is a b****.

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm w 1.4x TC (@ 850mm), 1/750s, f/5.6, ISO 720

31

Shot of the Month – October 2016

Last month’s image was a cacophony of color amongst the trees. This month’s image captures the quiet stillness of shades of gray by the waters edge. I love how the image transitions from pure white in the upper left corner through shades of gray to deep black in the lower right corner of the image. On this sunless morning in Vermont the lake was quiet and there was no wildlife to be found. While drifting along in my kayak, with not much to do, I came upon this spider’s web and decided to experiment and see what I could come up with. While shooting this image my main focus was on trying to capture the glistening dew drops on the spider’s lair. I paddled around and around trying every position imaginable until I found the angle that worked best. The image was shot with a point-and-shoot camera (Canon G1X).

Converting the photo to black and white was rather easy given that there was virtually no color to be found in the scene. Other than the two corners, most of the image is filled with shades of gray.

Turns out that creating gray can be a rather complicated affair. In the art world painters create different shades of gray by mixing black and white paint in different proportions. Want a darker gray? Add more black. Lighter gray? Add more white. You get the idea. A mixture of just black and white creates a “neutral gray.” Add a bit of yellow, orange or red and you can add a warm cast and create a “warm gray.” Add a bit of green, blue, or violet and you can get a “cool gray.”

In the world of print the CMYK color model is used — cyan, magenta, yellow, and black. All colors are made from a combination of these four colors. To make gray you add equal amounts of cyan, magenta and yellow.

TV and computer screens use a RGB color model – red, green and blue. Red, green and blue light at full intensity on the black screen makes white; by lowering the intensity one can create shades of gray.

On this particular day mother nature made graduations of gray by blocking out the sun with a heavy shroud of fog with a dab of dew thrown in for good measure.

I have to say, I am a big fan of her work……

Until next month…

Canon Powershot G1 X, @ 17.2 mm, f/5.6, 1/60 s, ISO 200,

30

Shot of the Month – September 2016

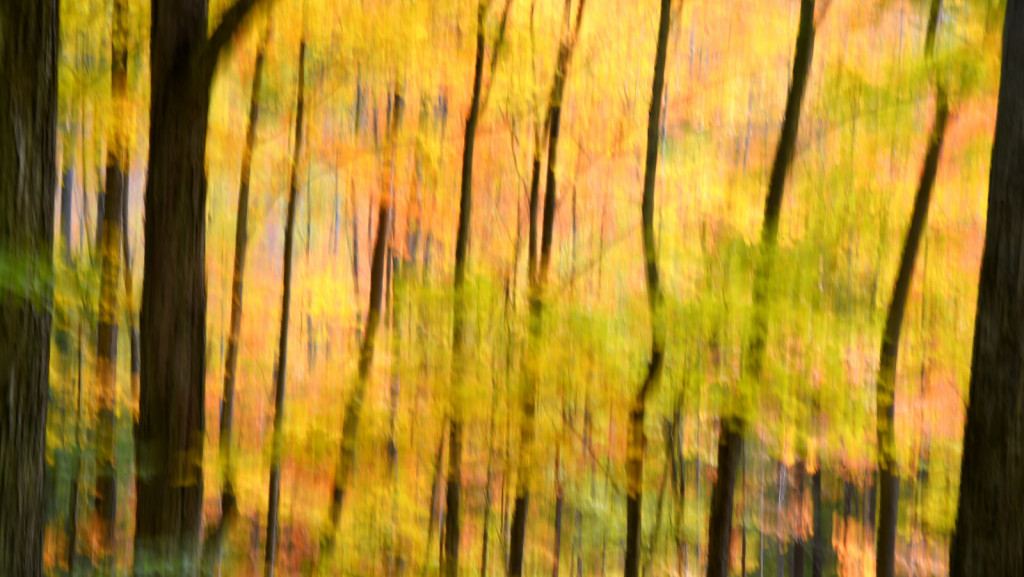

If you dig color then autumn in New England is the place to be. For a few glorious weeks, your entire world becomes a crazed canvas of exploding greens, yellows, oranges, and reds. As a photographer, I have often struggled to capture the scale and audacity of the landscapes that Mother Nature majestically painted each year. The colors in the image never seemed to quite capture the radiance and intensity that assaulted (in the most pleasant manner, mind you) my eye. The scale was always far too pedestrian — either too close, too far, or just never quite right to inspire and capture the sense of awe I felt in the field.

However, last fall I experimented with a motion blur technique that I read about in one of my photography magazines — the Vertical Pan. For the first time, I created images that conveyed the cacophony of color that enveloped me on my walks through the woods. Realism is nice, but these images much better reflect the imprint these experiences have left on my being.

There are three parts to this technique:

Find a Scene that Strikes Your Fancy

Get out there and walk around and look for scenes with bold colors, or great contrast in texture, or some cool shaped tree trunks, or a nice mix of colors…or…or…

Low Shutter Speed

The slower the shutter speed, the greater the blur and the more abstract the image. I experimented with shutter speeds that ranged from 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, 1/10, 1/20, and 1/30th of a second. There is no right speed. It depends on the scene before you and the look that you are going for. To lower the shutter speed you can set your ISO at its minimum and then close your aperture till you get the shutter speed that you want. On bright days, you may need to use a polarizing filter to help slow things down, or you can use a neutral density filter to reduce the light to your camera sensor to get slower shutter speeds.

Move the Camera

Point your camera at the scene of choice and lock the focus. Then, as you press the shutter release button to expose the image tilt the camera down with a smooth motion. Again, you will need to experiment to find the right mix. You can tilt slowly, quickly, or somewhere in between. Sometimes I begin the pan before I release the shutter button. You can pan down (my usual preference), up, or to the side.

There are endless possibilities. Keep playing with the shutter speeds as you vary your movement of the camera. Most will look like junk. Delete and move on.

Others will be, well, magical.

(I recommend viewing the images below on the biggest screen you can find. And once you click on one, you can move through the series easily by using your right or left arrow button.)

- See the falling leaf??!!

- Horizontal Pan

- Horizontal Pan

Until next month…..m

Nikon D4S, Nikkor 28-105mm (@ 105mm), f/29, 1/8 s, ISO 400

31

Shot of the Month – August 2016

Snakes tend not to be a crowd favorite but nature’s beauty comes in many sizes and shapes. Ok, while these Common Garter Snakes (CGS), photographed in Baxter State Park in Maine are not adorable, nor cuddly, I think that they do have a certain charisma and geometric charm about them.

If you get out in the woods, even a little bit, there is a good chance that you have seen a garter snake. They are by far the most common snake in North America and can be found from Canada to Florida, from the Pacific to the Atlantic coast, and most places in between. The CGS is quite adaptable and can live in forests, fields, prairies, streams, wetlands, meadows, marshes, and ponds – it is often found near water. These snakes are quite harmless though some species of garter snake have a mild neurotoxic venom that may help to immobilize its prey, but its bite is harmless to humans.

Common garter snakes are thin and tend to be about 22 inches in length and rarely get longer than four feet in length. Given their relative small size the CGS is often preyed upon by large fish, hawks, crows, bears, turtles, birds, foxes, squirrels, raccoons, bullfrogs, and some other snakes.

I know that some people get very afraid when they see a snake. Trust me, this fellow is not a threat. His main prey is, are you ready for this? – earthworms. Yep, this snake is a viscous killer of,  earthworms. See, now don’t you feel a bit silly? CGS are also very good swimmers and will hunt small fish, frogs, tadpoles, leeches, insects, slugs, and crayfish. They will also hunt for small mammals and birds when possible.

earthworms. See, now don’t you feel a bit silly? CGS are also very good swimmers and will hunt small fish, frogs, tadpoles, leeches, insects, slugs, and crayfish. They will also hunt for small mammals and birds when possible.

From the photo, you might deduce that all CGS are small, brown, striped snakes. Alas, life is not that simple. Turns out that there is tremendous variability in the appearance of the CGS and you may find them adorned in green, blue, yellow, gold, red, orange, brown (as above), and black. The CGS is just one out of thirty species of garter snakes that exist, not to mention the various sub-species, so figuring out which is which can be tricky. Check local reference guides for the state where you saw the snake for more precision on the colors typically found there.

So the next time you are in the woods and you see one of these fellas, take a deep breath, relax, and enjoy one of nature’s lesser-appreciated beauties.

Until next month…..m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 70-200mm @ 200mm, f/11, 1/60 s, ISO 400

31

Shot of the Month – July 2016

It was over in an instant. This “Awwwwwl”-inspiring shot of an Atlantic Loon chick riding on its parent’s back was taken in 1/1,000th of a second. Sounds easy and pretty painless. But not so fast Speed Racer — it also took me four years to get my kayak in the right spot to capture this scene.

Why so long you ask? Let’s break it down.

Atlantic Loons, aka Common Loons, spend the spring and summer on lakes and ponds in Canada and Northern US where they breed and raise the next generation of aquatic birds. During the first 2 weeks of life, the tiny chicks can often be found riding on the backs of the adults. Besides being incredibly cute, this behavior helps promote the survival of the wee birds. When so small the chicks are very buoyant and they have a hard time maneuvering in the water on their own. Keeping the chicks off the water also helps avoid the dangers from below, such as from large-mouth bass, and avoid danger from above in the form of Bald Eagles (Source). I have often seen a Bald Eagle circle above a loon family waiting for a chance to pick off a chick. Also during the first two weeks of life, the loon chicks are not able to effectively regulate their body heat and they lose a lot of heat through their feet when in the water. Riding on a parent’s back helps keep them warm and if necessary the chicks can seek shelter under a protective wing (Source), as seen below:

So my challenge was to be in the right place at the right time to capture a behavior that only takes place during just a part of a two-week window each year. And in good light, of course.

In year 1 I had just moved to Vermont and I didn’t know anything about loons, their behavior, where to find them, etc. By the time I discovered my first mating pair, it was too late in the summer and the chicks were too big for back riding. Perhaps next year.

In year 2 I returned to the same pond and monitored the breeding pair as they built their nest and incubated the eggs. For some reason the eggs failed and no chicks. Sad. Maybe next year.

By year 3 I was now tracking loons at two different ponds. In pond #1 the nest was flooded during a thunderstorm and the eggs were lost. At the second pond, I arrived too late (working for a living often gets in the way of photography) and I missed the behavior. Well, there is always next year…..

In year 4 I was tracking loons in three different ponds. In site #1 the nest failed. In site #2 the pair was successful and I managed to catch a couple of days of the behavior and captured a few good shots. In site #3 I found the chicks on what must have been day 2 or day 3 of their young lives. Bingo!! For the next 10 days, I returned to the pond before sunrise each morning and spent a few hours with the loon family before heading off to work.

It was a magical two weeks as I had the chance to glimpse through a fleeting window of opportunity and share in the loons’ first weeks of life. The experience was definitely a highlight of my time living in New England!

And the image was well worth the 126,144,000.001 second wait.

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm, 1.4 TC (effective 850mm), f/8, 1/1000 s, ISO 2500, +0.333 EV, handheld from a kayak

30

Shot of the Month – June 2016

This month we get a lovely rector-verso view of the Little Bee-eater (LBE) – a dandy little bird in every sense.

Dandy: “…is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance, refined language, and leisurely hobbies….”(from late 18th and 19th century Britain)

The LBE is definitely a stunner — both male and female (as seen in this photo) are adorned in a shimmering coat of green, yellow throat, offset with a black gorget, a luxurious rich brown upper breast that fades into a buffish ochre on the belly. And that daring dash of aqua (?) above the eyes. Bold and beautiful.

As for the leisurely hobbies – seems that LBEs spend about 10% of their time engaged in “comfort activities.” This would include sunning themselves, dust bathing, and water bathing. Dust bathing?–yeah, it helps protect against parasites like mites and flies. (source)

Dandy: “An excellent thing of its kind”

As the title says, Little Bee-eaters are dandy flyers. Little Bee-eaters catch all their prey while on the wing. If an insect lands on the ground the bird is no longer interested. As their name gives away, LBEs eat mainly bees, wasps, dragonflies, and similar insects. These birds typically hunt from a favorite perch – once a flying insect is spotted, the bird launches into the air, snatches the insect with that powerful, forceps-like beak, and dines while flying or returns to the perch. Insects with stingers (da-bees) are thrashed against a tree branch as the LBE pinches tightly on the insect to squeeze out all the venom. (source)

I photographed this couple in Botswana. I also photographed a Blue-cheeked bee-eater in Botswana and you can see some of that dining-at-the-perch behavior here. (you really should, it is a great shot if I say so myself)

The Little Bee-eater is indeed little. There are 26 species of bee-eaters in the world and the LBE is the tiniest of them all. What they lack in size they make up in numbers. It is estimated that there are 60 to 80 million Little Bee-eaters spread out across Africa. The bee community must be very bummed about that fact!

Ahhh, the lovely little bee-eater, beautiful but deadly, especially if you are a bee.

Until next month….:-)

Nikon D70, Sigma 300-800mm (@650mm), 1/400 s, f/5.6,

31

Shot of the Month – May 2016

Did you know that it is impossible to take this picture, as shot, with today’s cameras?

Uh, you mean the one I am looking at right now.

Yes, that one.

The one that doesn’t exist.

Exactly.

Scratch head…

Photographic equivalent of “Who’s on First?” (If you have never heard this, stop now, and listen…Comedy Classic!)

Obviously, I did create the image so it does exist. However, this is not one picture but 7 that have been merged together to accurately represent the scene as I saw it with my eyes.

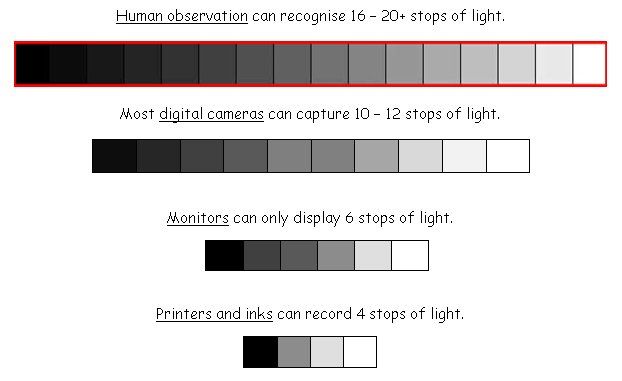

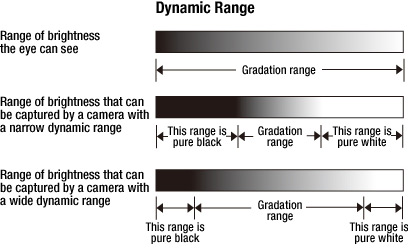

Today’s digital cameras are amazing, but they still cannot see the world as accurately as the human eye can, yet. Humans are capable of seeing about 24 different levels of brightness in a scene. In photo lingo, we would say that people can see close to 24 stops of light, or 24 Exposure Values (EVs). Today’s best cameras can see about 10-14 stops of light. Some scenes have a high dynamic range, meaning that there is a large difference in Exposure Values between the darkest shadows in the scene and the brightest highlights.

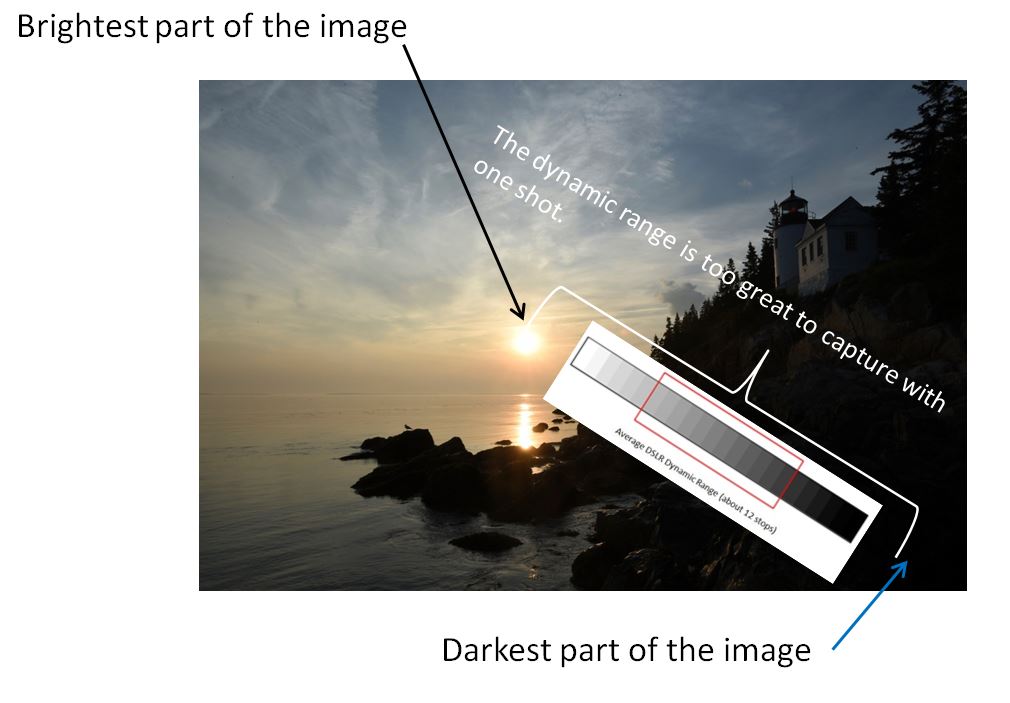

The dynamic range of this sunset scene is beyond the capability of my camera. I could expose for the sun (see the image below that was underexposed at -0.66 EV, but then the rocks in the lower right would be completely black – you would lose all the detail in that part of the picture. Or, I could set my camera to expose properly for the rocks, but then the sun would be drastically overexposed and just be a white mess (as you can see in the image below that was shot +2 EV ).

Pack up and go home? Nope. One solution is to use “High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography techniques. In HDR photography one takes multiple shots where each image is exposed differently to capture the full range of brightness levels in the scene. For this image, I took 3 shots that were increasingly “underexposed”, one shot that was “properly” exposed (the camera’s best guess under the circumstances), and then 3 shots that were increasingly “overexposed.” Here you can see each shot in a row, with the most underexposed image to the far left, and the most overexposed to the far right.

Through the wonders of software, I was able to merge these shots so that each area was properly exposed in the final image.

Typical scenes that will challenge the dynamic range of your camera include backlit scenes (strong sun behind your subject), bright skies, interiors (if there is a window present you will probably have a problem), and scenes that include a strong light source.

Most cameras have an “Auto-HDR” mode. Yes, iPhones and similar smartphones (Samsung Galaxy) have them. When faced with such a scene turn on the HDR function and see if it helps.

As you can see, although the technology keeps getting better and better (just a few years ago most cameras could only capture about 5 stops of light), we still have a ways to go before matching human eyesight. In the meantime, with proper use of HDR, you don’t have to let too many stops, stop you from getting that great shot.

Until next month….michael

P.S.

Here is an article that also explains dynamic range, amazingly, using the same scene as an example!

Also, did you notice the lone seagull on the rocks?

Bass Harbor Head Light Station, Acadia National Park, Maine

Nikon D4S, Nikon 17-24 mm (@ 24mm), f/22, ISO 200, variable shutter speed for 7 shots at -2 EV, -1.33 EV, -0.667 EV, 0 EV, +0.667, +1.33 EV, +2 EV