31

Shot of the Month – October 2024

I stood by Reflection Lake in the late afternoon with low expectations. I have never had much luck getting a good shot of Mt. Rainier at this time of day – usually, too much wind to get a reflection and rarely any good clouds. I actually left my camera in the car figuring I would enjoy the scene like a normal person. But then I almost jumped out of my skin when the clouds suddenly rolled in and the low sun started to bask them in warm light. And the air was unusually calm allowing for a great reflection. I ran and got my gear and started shooting.

Click here for more on this photo hotspot:

Many non-photographers are surprised to learn how important clouds are to creating a compelling sunrise/sunset landscape image.

How important? Well, I know many a landscape photographer who will skip a potential shoot if there is a forecast for no clouds. Clouds are so important that there are apps to predict the timing, height, and density of clouds for a given location. Most serious landscape photographers have at least one or two of these apps on their phones and study them judiciously before heading out for a shoot. Some include Clear Outside, Astrospheric (IoS, Android), and Windy.com (IoS, Android).

There is no doubt that the sun sinking beneath the horizon on a cloudless night at the beach can be serene, beautiful, and romantic…. But it rarely makes for a compelling image. Clouds, when at the right height and density catch the sun’s glorious first or last rays of red, orange and yellows that humans love. Clouds create drama and make an image more visually striking.

For example, this is a nice sunrise shot I took at Swiftcurrent Lake in Glacier National Park:

But look at what clouds can add to the scene:

(Ok yes, I found a better/more compelling foreground in the second image, but you still get the idea. That sky is more dramatic and interesting)

In this sunset scene at the same location I had clouds but they were too dense to allow the colors to come through. My solution was to go for a very long exposure that allowed the motion of the clouds to add drama and visual interest to the scene.

Read more about the story in getting these shots at Swiftcurrent Lake here:

The shot below of a tulip field at sunrise had some real potential but in the end fails due to the lackluster sky. Nary a cloud….sigh.

In the image below at Rialto Beach the dramatic foreground and compelling silhouette make this a decent image but a few more clouds to catch some color would have taken it to another level:

See more on Rialto Beach here: Rialto Beach

And in this next shot of the Lime Kiln Lighthouse we have juuuust enough clouds to make it a usable image:

But if I crop the image, to allow the clouds to fill more of the scene, I find it more compelling:

Click on the box to read more about how I got the shots at the Lime Kiln Lighthouse: Landscape to Lovers

As you can see, a cloudy day is not always a bad thing. And if you happen to be a landscape photographer, clouds are often essential to making our day into something special.

Until next month….michael

30

Shot of the Month – September 2024

I don’t even know where to begin.

How do I describe this magical place? In our age of hyper-sensationalism, where a new cookie flavor is “revolutionary” and the latest TikTok dance is “epic,” many superlatives have lost their punch and meaning. But let me tell you, my dear friend, Patagonia is the real deal. Stunning. Awe-inspiring. Breathtaking. Majestic.

Tolkien’s Middle-earth has nothing on this place.

Where is this Magical Land?

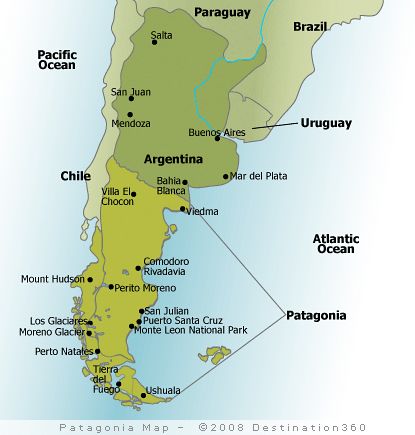

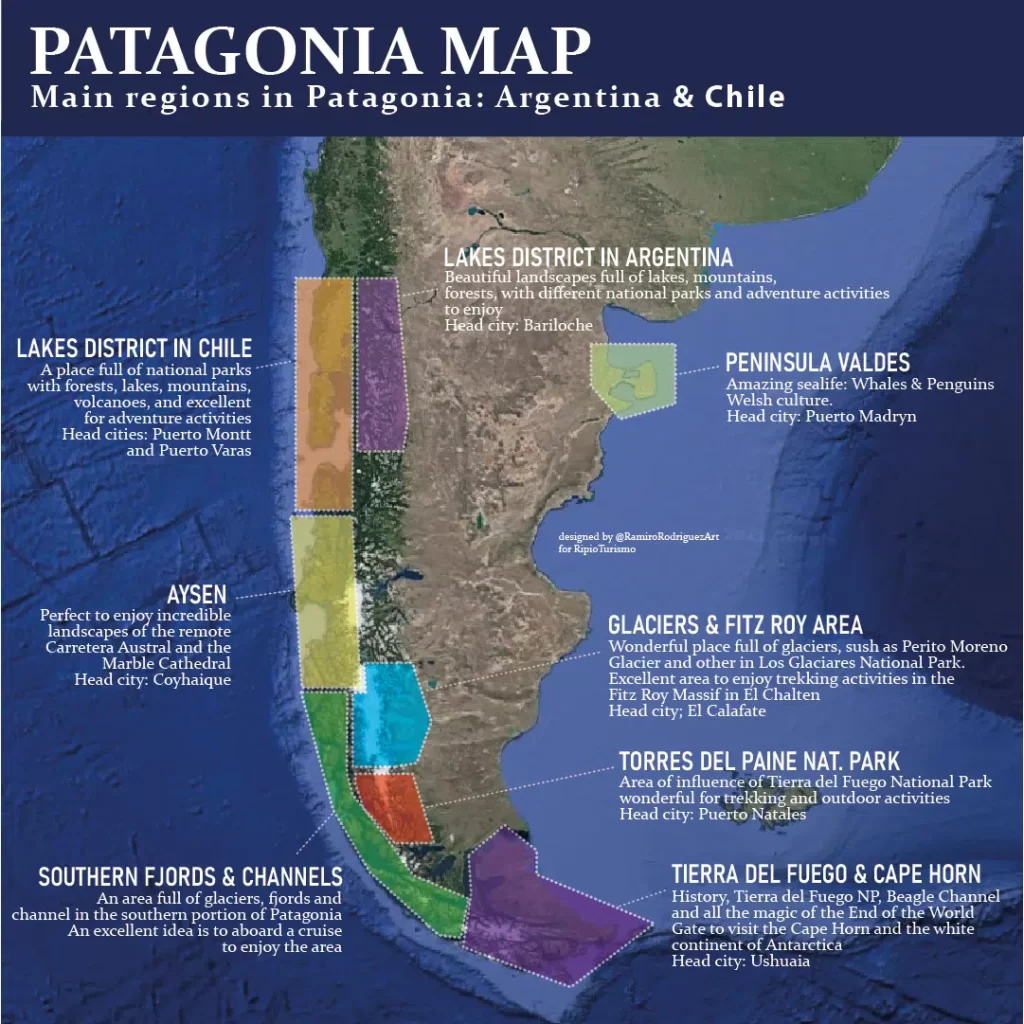

Patagonia covers a massive region at the bottom of South America.

Patagonia is about 300,000 square miles (1 million square kilometers) in size and spans the countries of Chile (to the west) and Argentina (to the east). It is an area larger than 80% of the countries on earth, yet is one of the least populated areas on the planet (1-2 persons/sq km).

Stunning landscapes and no people?? My kind of place!

The southern Andes mountain range dominates the landscape in many places. It really is at the end of the world – the most southern tip is the starting point for voyages to Antarctica.

Argentina contains 90% of Patagonia, which spans one-third of the country. Ten percent of Patagonia is located in Chile, covering half of the country.

What is Patagonia?

Patagonia is a collision of habitats and landscapes, including towering mountains (Andes), crystal blue lakes, massive glacier fields, temperate rain forests, deep fjords, and huge deserts. Mother nature worked overtime here offering a bewildering array of habitats and biodomes. The area is also home to a stunning diversity of wildlife including puma, guanacos, Andean condors, penguins, pygmy owls, fur seals, flamingos, whales and…so much more.

Watch this great video to get a sense of the variety of landscapes that can be found in Patagonia:

Chilean Patagonia is famous for its dramatic scenery – towering mountains, sprawling glaciers, and pristine fjords. We visited a ranch in Chile that borders the iconic Torres del Paine National Park in search of pumas. Each day on our hikes we were greeted with one stunning scene after another. I shot the image above with an iPhone as I walked up to the river’s edge.

Landscape photographers must lose their minds in Patagonia. How do you choose which scene to shoot when stunning vistas are found in every direction? Here is just another “average” sunrise:

And another:

So yes, I fell in love with the place. So much so that we scrapped our original travel plans for 2026 (sorry Madagascar) and instead will return to Patagonia for more soul-filling vistas, once-in-a-lifetime animal encounters and glorious solitude that can only be found at this remote, rugged edge of the planet.

And we had some amazing luck with the wildlife…but more on that in future posts.

Until next month….michael

Sources:

Chilean Patagonia vs. Argentine Patagonia: Which is Right for You?

10 incredible facts about Patagonia

Apple Iphone 14 Pro, 14mm, f/2.2, 1/1250 sec, ISO 40

31

Shot of the Month – August 2024

When on safari my head is always on a swivel as we drive across the savannah. I peer left and right as my eyes scan the bushes and grasses for lions and cheetahs. When near trees I stick my head out the window, strain my neck, and squint my eyes to look up into the canopy in search of a leopard amongst the limbs and shadows. Imagine my surprise on this day in the Serengeti when I looked up and saw….a lion??! What is this lion doing relaxing up on this branch, rather far from terra firma?

Leopards take refuge in trees out of necessity – they live and hunt alone and cannot defend their meals against larger predators like lions and hyenas. Leopards evolved over millennia to be natural tree climbers so they can cache their meals high up in trees to be out of the reach of their thieving competitors.

A leopard with its kill in a tree:

Lions have no such need — they are the largest predators in their habitats and live in prides with 3 to 40 members (average size is 15) allowing them to defend their meals with ease.

And while leopards are perfectly built to climb trees, lions are not. Leopards are relatively light (ranging from about 50 to 160 pounds) and their shoulder blades are proportionally bigger, flatter, and more concave than a lion’s. Lions are built with enormously powerful forequarters and a very stiff back which is useful for wrestling heavyweight prey, such as buffalo to the ground. However, the lion’s powerful build reduces agility and vertical leaping ability, making tree climbing more difficult. Male lions can weigh 400 pounds so jumping out of a tree presents a real risk of dislocating a limb when landing with a thud back on earth.

There are currently about 21 countries with lions and the fact is that the vast majority of said lions never climb a tree. But, lions can learn to become tree climbers when the conditions are juuust right. For example, the lions in Queen Elizabeth National Park in Uganda are famous for their tree-climbing ways. Why there? Scientists note that the prides in this park tend to be smaller and share the habitat with large herds of buffaloes and elephants. Scampering up the local tree is a good escape plan when faced with a stampede of buffaloes. (See the Queen Elizabeth NP lions here.)

Lake Manyara National Park in Tanzania is another location well known for its arboreal-minded lions. Scientists noted that a very heavy rainfall in 1963 created a plague of Stomoxys biting flies and drove the resident lions up trees and down warthog burrows to escape the insects that caused open wounds and deadly infections. Lions have been seen climbing trees in this park ever since.

Tree-climbing lions have also been spotted in the Tarangire and Serengeti National Parks in Tanzania. More recently a lion pride in Kruger National Park in South Africa has been observed climbing trees.

So while seeing a lion in a tree is not common, it also is not unheard of. This behavior is usually based on unique circumstances and local conditions. Lions seem to climb trees to:

- Avoid insects

- Avoid heat (they can find a nice breeze a bit higher off the ground)

- Look for prey

- Steal prey from leopards

Lions can only climb trees if their local habitats have trees that are “lion-friendly.” This means trees with strong, low branches that can support cats weighing anywhere from 250 to 400 pounds. For example, the African sycamore fig trees or umbrella acacia thorn trees often have horizontal branches not too far above the ground and tend to be lions’ preferred “jungle gym.”

Once a pride experiences the benefits of tree climbing they can take to it with enthusiasm. The behavior is then passed down from one generation to the next.

You get entire families — adults, youngsters, everyone — up trees. Generation after generation, it really has become a habit to go up in the trees. It just gets entrenched as a culture because it’s fun.”

Dr. Luke Hunter

Lions tend to be much better at climbing a tree than getting down. It can be painful (and hilarious) watching these massive beasts awkwardly trying to exit a tree – the dismount can quickly become a Mr. Bean sketch.

Here is a video with a good summary on how and why lions climb trees:

Here we see lions trying to get a leopard’s kill out of a tree: (You can see how the large male lion struggles at tree climbing)

And here is a crazy interaction between a lion and a leopard in a tree that shows why lions need to be careful to stay on limbs that can support their weight! (The action starts at 0:25 seconds)

Sooo, next time you go tree climbing in your local safari park, look up first to see what may be “lion” around on the branch above. (Really? You didn’t see that coming??)

Until next month……michael

Sources

Wild Cats 101: Why Do Lions Climb Trees?

Why Do Some Lions Climb Trees? A closer look at tree climbing lions

Facts About the Tree Climbing Lion of Tanzania

Why Don’t All Lions Climb Trees? (NY Times)

Nikon Z9, Nikkor Z 100-400 mm (@190mm), f/5, 1/320 sec, ISO 200, EV +0.667

31

Shot of the Month – July 2024

Ouch! That is going to leave a mark!

If you look closely you will notice that the seagull on the ground has clamped his beak onto the body of the gull taking off – trying to hold him down. The adult (in white) is outraged that the younger bird (as seen in his grey, not yet fully developed plumage) has just stolen his fish (see the fish?).

So what’s going on here?

In this scene, seagulls have gathered along the shoreline to take advantage of fish spawning nearby. Each year the congregation of fish attracts a myriad of predators looking to dine on the bountiful feast. As the tide recedes the seagulls are usually the first to appear to try their luck in catching the stranded fish.

When I took this image there were probably several dozen photographers nearby. Despite the crowd, I am probably one of the few to get this shot. Perhaps the only person. Why is that? Generally, seagulls don’t get much respect from the wildlife photography crowd. Seagulls lack the dramatic looks and charisma of the predator that has drawn so many people to this location. Most photographers keep their cameras off until these guys show up:

In fact, I often annoy my photographer neighbors — when they see me firing off shots some will jump to their cameras thinking a bald eagle is coming in. In the background I hear the resentful grunt of disapproval …”Ugggh, it is just a seagull,” as they fill with chagrin for getting their hopes up over nothing. I imagine that a few were shaking their heads wondering if I was some newbie or just a simpleton for wasting time on such pedestrian subjects.

Most people are not very fond of seagulls. People find gulls annoying given their riotous loud squawks and thieving ways – ever been dive-bombed by seagulls at the beach as they try to steal your french fries? Why are they swarming around an empty parking lot? And loitering around trash bins doesn’t help their image.

I get it, they can be a nuisance.

However, our collective disdain for gulls is unfair and at odds with the facts. Seagulls have a lot going for them:

- Seagulls are highly adaptable and have managed to thrive across a broad range of habitats spanning the planet. They can be found from the Arctic to the Equator and most places in between.

- These birds are resourceful, inquisitive, and generally, “wiiicked smaaart” (any Good Will Hunting fans out there?). Seagulls are among the few animals documented using tools putting them among an elite group. Seagulls have been recorded using bread as bait to catch fish. I have seen seagulls drop clams on rocky beaches to break them open. The clam-breaking behavior is not innate and must be taught by the older gulls to younger birds.

- Often to our annoyance, seagulls have adapted well to human society and thrive in our urban environments. In some cities, gulls have learned how to use crosswalks to traverse the road safely while scavaging for food.

- Seagulls have expansive diets and are opportunistic feeders – they can consume anything from fish to insects to fruit to human food scraps allowing them to thrive under a broad range of environments.

- They are very successful hunters and will adjust their hunting style depending on the prey available.

- Seagulls have been seen cooperating with other species to allow both to benefit from a food source. They often live in complex social groups and will warn other seagulls of impending danger.

- Most seagulls live near the ocean and they have developed the ability to drink salt water when fresh water is not available. This ability is a game changer and allows the birds to travel far and wide without worrying about finding enough water for survival.

There are over 50 species of seagulls but in some habitats, extensive cross-breeding (hybridization) makes identification very difficult. The term “seagull” has no scientific meaning — it is just used informally by folks like me when we don’t know exactly which species we are looking at. In my image above the birds are most likely Glacous-winged gulls as they are very common in the Pacific Northwest where this image was taken. But seagull species identification gets very complicated, very fast. Check out this link to get a sense of the chaos and follow this link if you really want to go down the rabbit hole on gull taxonomy.

To be honest part of the reason I photograph seagulls is to practice my panning technique and verify my exposure settings so I am “game ready” when the bald eagles take flight. However, I do like the challenge of trying to capture an interesting image of a bird that most people aren’t interested in seeing. Can I overcome that inherent bias?

A few more images from my time by the water’s edge. In this image, I like the blurred background and the simple primary colors of blue and white. It has the look and feel of a painting.

In this early morning shot, we are still in the blue hour as the delicate lighting illuminates the gull.

In this image the lighting is exquisite and the water splash highlights the action. The dark background allows the birds to really pop and I like the reflections in the water.

Here a seagull has just caught a fish and begins to leap toward the sky. The just-strong-enough light illuminates the bird perfectly while the fish seems to shimmer in gold.

The water splashes and body postures in the image below scream “Action” as the chase begins. The light, reflecting up from the water, fills in the shadows allowing us to really see the beauty and delicate nature of the bird’s feathers and wings. My eye is drawn to that very sharp, open beak of the gull in the rear as he comes in for the attack, adding to the drama.

To their credit, seagulls seem rather nonplussed by our opinions – whether we gaze on with wonder or contempt. Like Jonathan Livingston Seagull, they just seem to fly higher and higher and thrive all around us. Bully for them!

Until next month…..michael

Sources

Glaucous-winged gull (Wikipedia)

65 fun and interesting facts about seagulls

Nikon Z9, Nikon 600 mm, f/4, 1/1600 sec, ISO 1000, -0.7 EV

30

Shot of the Month – June 2024

“Wow”

“Whoah”

Audible gasp.

When I show this photo to someone these are some of the “typical” responses. And I have to be honest, they are sweet, sweet music to this photographer’s ear. These exclamations are the audible clue that we have an image that is perhaps a bit special. An aural sign that I have captured an image that gives a hint of the awe-inspiring beauty that can be found in nature.

Not surprisingly the dramatic impact of side lighting helped transform this shot to gasp-worthy stuff. The spectacular water highlights convey a sense of action and give this static shot a sense of motion and chaos. Even though we can’t see much of the brown bear as he shakes off the water after a recent dive for a fish, the shot is a visual winner.

I photographed this Brown Bear at Katmai National Park in Alaska. You can read more about brown bears here:

When the action started I managed to take 12 shots in quick succession but I liked the first one best, as shown above. The next frame in the sequence is ok, but I prefer the head tilt in the first shot:

After the shake-off the bear continued to walk across the river and the backlighting produced this nice rim-lit shot:

Perhaps I have stumbled across my “signature” shot – the “Spin Cycle” as I originally captured with this moose years ago:

Click the button to read about how this shot happened Spin Cycle

It is always fun catching Mother Nature working her magic alchemy with a bit of water, dramatic lighting, and a charismatic beast.

Until next month….michael

Click here to see my post about the power of backlighting: Back for the Drama

Nikon Z9, Nikon 80-400mm (@350 mm), f/5.6, 1/1600 sec, ISO 900, EV -0.333

31

Shot of the Month – May 2024

Wow, look at this guy! Now, THAT is how you make an entrance in style! This splashy, multi-hued fellow is a Mwanza Flat-Headed Rock Agama (MFHRA) – his name is almost as long as the list of colors covering his body.

There are about 30 species of agama lizards (in the family Agamidae for you science types) with most found across Africa though you can find a few in southeastern Europe and central India. The MFHRA is found in Tanzania, Rwanda, and Kenya. I photographed this flashy stud in Tanzania.

Based on this photo it is hard to believe that Agamas are usually adorned in brown or gray. Each year the drab males transform into this cacophony of color during the mating season to dazzle the females and win a mate. Check out the range of colors on this bold male. At his head, we start with shades of dramatic pinks and oranges. His upper torso is primarily colored in orange. Then we transition to shades of blue on the lower body, tail, and legs.

Like all reptiles the MFHRA is covered in scales, and in this case, very colorful ones at that. The scales are made of alpha and beta-keratin (Our fingernails and hair are made of keratin). Lizards often live in hot, arid climates and the scales help trap moisture inside the body and sometimes can be used like a suit of armor, protecting the body from bites and scrapes.

Did you notice those crazy-looking toes/fingers???

Agamas are active during the day and dine primarily on insects though they will eat eggs of other lizards and occasionally feed on grass, berries, and seeds. The Mwanza flat-headed rock agama lives in semideserts and can often be found basking on rocks or kopjes.

You can read more about agama lizards, and their silly behavior, in my post about a Red-headed Agama (shown below) that I photographed at the Lake Nakuru National Park in Kenya.

Click the button: Attitude a la Agama

Yeeees, I know. It seems that the Red-headed agama can also have orange-colored heads. Go figure…

Until next month….

Sources:

Wikipedia (Mwanza flat-headed rock Agama)

The Role of Scales on Reptiles and Fish

Nikon Z9, Nikon 100-400 mm (@ 310 mm), 1/640 sec, f/10, ISO 2200, EV +1.0

30

Shot of the Month – April 2024

This month we visit with the gorgeous Yellow-collared Lovebird (YCL). I photographed this small group of birds in the Tarangire National Park in Tanzania. The YCL, also known as the masked lovebird or the eye-ring lovebird is a small type of parrot.

There are about 410 species of parrots and most are found in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Parrots have strong curved beaks, an upright stance, and clawed feet. Of this large group of birds, only nine are in the lovebird genus.

The YCL is a colorful explosion of greens and yellows with a black head, bright red beak, and white eyerings. Lovebirds get their name from their affectionate ways. You can often find them sitting together for long periods as they get, well, all luvvy-duvvy with their mate. They are very social birds, very affectionate, and form strong monogamous pair bonds.

Humans are fascinated with Lovebirds, and their parrot brethren, and they are popular pets.

Sadly, humans are loving these birds to death. How bad could it be? Let’s break it down:

- One-third of all parrot species are threatened with extinction due to the pet trade, hunting, habitat loss, and competition from invasive species.

- As of 2021 about 50 million parrots (half of all parrots on the planet) live in captivity (cages) with most being pets in people’s homes. Every year over 16 million parrots are traded in captivity.

- The Fischer’s Lovebird (looks just like the YCL but with an orange head) was the most trafficked bird species in the world through the 1980s and not surprisingly their population plummeted 30% since the 1970s. Only 200,000 to 1 million birds remain in the wild.

- Somewhat encouragingly many countries now forbid the trade of exotic birds. The US was the largest importer of wild birds until 1992 when it finally passed the Wild Bird Conservation Act (WBCA). The European Union didn’t pass its ban on importation of wild-caught birds until 2007! Despite these efforts, the illegal trade of parrots and other birds is still thriving. For example, approximately 2 million Fisher’s Lovebirds were captured in the wild and traded illegally between 1976 and 2016. Lovebirds are often given as Valentine’s Day gifts…sigh….

- Finding it increasingly difficult to secure wild birds the pet trade industry shifted to breeding birds for the ever-growing demand for feathered pets. Think puppy mills, with all the horrors that go with that, but for birds. Industrialized operations often house hundreds of birds in rows of barren cages and deplorable living conditions. Parrots are highly intelligent and such conditions can cause the birds severe mental and physical impairment and trauma.

- Parrots can be very affectionate and cute when young but if not raised and trained properly can become aggressive and may bite causing serious injury. After a few months, many buyers find the demands of caring for a bird to be too much leading to parrots being surrendered and rehomed FIVE times before finding their final home or dying prematurely from neglect and abuse. Parrots require an enormous amount of care, attention, and intellectual stimulation to thrive and many owners are not ready or able to meet these demands leading to traumatic lives for the parrots.

A common problem is that large parrots that are cuddly and gentle as juveniles mature into intelligent, complex, often demanding adults who can outlive their owners, and can also become aggressive or even dangerous. Due to an increasing number of homeless parrots, they are being euthanised like dogs and cats, and parrot adoption centres and sanctuaries are becoming more common. Parrots do not often do well in captivity, causing some parrots to go insane and develop repetitive behaviours, such as swaying and screaming, or they become riddled with intense fear. Feather destruction and self-mutilation, although not commonly seen in the wild, occur often in captivity

Lovebirds and parrots have complex dietary, social, intellectual, and emotional needs – placing them, often alone, in a barren cage, for 10-80 years (some parrots can live a LONG time) is cruel and unusual punishment.

“Polly want a cracker?”

F*&$ that! Polly wants to be left alone.

Until next month…..michael

Sources:

Animal Welfare Institute – Bird Trade

Freedom for Animals (Blog: LOVE BIRDS? IF YOU DO, LEAVE THEM IN THE WILD!)

Wikipedia – Yellow-collared Lovebird

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, 1.4 TC (850 mm effective), f/5.6, 1/500 sec, ISO 280,

31

Shot of the Month – March 2024

Above we have a classic scene captured on the plains of the Serengeti, the place of legend and lore for wildlife lovers around the world. A trip to the Serengeti is on many a bucket list for wildlife aficionados. And many lucky enough to make that “once in a lifetime” trip now seriously ponder if they can make it a “twice in a lifetime trip” as the draw to this magical place is overpowering.

Having lived in Africa for many years I had the good fortune of being able to visit “the Serengeti” on multiple occasions and it is always on my list of potential places to visit again. For the uninitiated, let’s break it down.

Where is it?

This wildlife mecca is found in Tanzania and Kenya, in East Africa.

What is it?

The Serengeti ecosystem is a geographical region spanning the Mara and Arusha Regions of Tanzania. This region is made up of a diverse habitats including riverine forests, swamps, kopjes, grasslands, and woodlands. Over 30,000 km2 (11,583 mi2) of this area is protected by a collection of national parks and reserves. Almost half of that area (about 14,750 km2 or 5,695 mi2) is part of the Serengeti National Park. Other protected areas nearby include

- Ngorongoro Conservation Area (8,292 km2) (3,202 mi2)

- Maswa Game Reserve (1,415 km2) (546 mi2)

- Grumeti Game Reserve (410 km2) (158 mi2)

- Ikorongo Game Reserve (600 km2) (232 mi2)

- Loliondo Game Control Area (6,200 km2) (2,394 mi2)

In southern Kenya, the northern tip of the Serengeti is protected by the Masai Mara National Reserve (1,510 km2) (583 mi2).

Serengeti Plains?

A large portion of the Serengeti ecosystem is a vast, flat, open plains, covered mostly in grass. This open grassland covers the entire lower third of the Serengeti NP. Plains are described differently depending on the climate they experience:

- Grassland (temperate or subtropical)

- Steppe (semi-arid)

- Savannah (tropical)

- Tundra (polar)

The vast expanses of grass in the Serengeti are therefore referred to as the Serengeti Savannah as it falls in equatorial (tropical) Africa. The Serengeti Savannah receives enough rainfall to support grass and some trees, but not enough rainfall to support a true forest. Trees tend to be scattered here and there across the plains. A savannah is a vegetation zone between a tropical rainforest and a desert. The area experiences a strong contrast in weather – the rainy season is intense with lots of rain, followed by extended periods of high temperatures and no rain.

While the Serengeti is the most well-known in Africa there are also savannahs in Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, and Namibia.

What makes it special?

The Serengeti has the largest concentration and diversity of wildlife on the planet. By the numbers:

- The Serengeti is home to the “Great Migration,” the largest movement of animals in the world. Each year over two million wildebeests, zebras, and antelopes traverse the grasslands (1.3-1.7 million wildebeests, 200,000 zebra, 500,000 Thomson and Grant’s gazelle) as they follow the rains in search of greener pastures and water. The Serengeti is home to an incredible diversity of herbivores that include cape buffalo (30,000), African elephant (7,500), giraffe (4,000), black rhinoceros (200), warthog (15,000), eland (7,000), waterbuck (3,000), topi (27,000) and many others.

- The Serengeti is famous for its collection of large predators that include lions (3,000), leopards (1,000), cheetah (250), and spotted hyenas (7,500).

- Africa’s “Big 5” can be found in the Serengeti.

- Bird lovers can find over 500 species of bird life in the Serengeti ecosystem.

No other location on the planet can match the sheer scale, density, and diversity of wildlife found in the Serengeti and it has been voted the top “Seven Natural Wonders of Africa.”

If you are up for an adventure definitely consider a visit to this magical place.

A black and white version for that old-timey look:

Until next month…..michael

A few more scenes from the Serengeti:

Sources:

Savanna Biome: Climate, Locations, and Wildlife

Difference Between Savanna and Grassland

Nikon Z9, Nikkor Z 100-400mm f/4.5 -5.6 VR S (@100mm), 1/400 sec, f/5.6, ISO 64, EV -0.33

28

Shot of the Month – February 2024

Each fall bighorn sheep rams gather at the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming (located just next to the Grand Teton National Park) in hopes of mating and passing along their genes to the next generation. Alas, only the largest and strongest rams earn the right to mate and often will have to fight other rams for dominance. These battles involve smashing those massive horns into each other with great force until one adversary relents:

But even after these brain-numbing battles, the victorious ram’s work is not done. Oh, no, far from it. Now the ram must court the females and stay by their side until one goes into estrus. He must be absolutely relentless in his surveillance. If she climbs up a mountain, he must follow. She goes back down, down he must go. He must fight off any male that approaches her. Day in, day out. Hour after hour. This behavior is called “tending” and is the most successful strategy for winning over a mate. Ewes are most receptive to tending males. (Sage female readers nod their heads in agreement…)

Some males may try a “blocking strategy” to keep a female from reaching the areas where rams are tending ewes. Other males fight a tending male but the ewes are usually not receptive to this approach. (More nodding among the readers….)

Once a female goes into estrus chaos ensues. The dominant male will chase her and attempt to mate but she will not give in so easily. She often spurns all suitors and forces the males to chase her for extended periods. She is testing the males to identify the strongest to ensure that only the best genes are passed on to her offspring. At times multiple rams will chase the ewe. As a ram was trying to copulate with a female I have seen other males dash in and head butt the male to break up the act. So rude!

Two males in pursuit of a female:

In this scene, eight males watch over a female! (she is the one at lower left in the image)

In the first image, I panned my camera to track the running sheep and used a slow shutter speed to blur the background. This is a high-risk technique – if my panning motion does not exactly match the speed of the running animals we end up with a blurry mess. Even if I get the panning right, the animal’s movement may still be at an angle that does not produce a pleasing image. Hundreds of attempts may only create one or two acceptable shots.

Or none.

The key is to keep shooting and taking as many images as possible with the hope that a few will work.

The panning blurs out the background and creates a lovely oil painting effect. The blurred feet of the sheep convey speed and give a sense of the pursuit and energy of the chase.

As you may have gathered, procreation for bighorn sheep is not for the faint of heart. Each fall a ram must endure a grueling gauntlet of battles and tests of patience and stamina that can last for months. All this to earn a few brief moments with an ewe and the possibility of passing on his legacy.

Until next month…

Sources:

Nikon D5, Sigma 150 mm – 600 mm (@ 600 mm), f/14, ISO 100

31

Shot of the Month – January 2024

This month we travel to Glacier National Park in northern Montana for an iconic view of Swiftcurrent Lake. I shot this image on the rocky edge of the lake looking west toward Grinnell Point – the tall peak in the center of the image. Grinnell Point is part of the Lewis Range of mountains. This spot is also the site of Many Glacier Hotel – this historic hotel was built in 1914 and commands epic views of the lake.

This image makes up the “Fire” part of this post. I arrived at the water’s edge long before sunrise and set up my tripod and camera. As I sat in the dark for the second morning in a row I had to wait for the sun to slowly climb above the mountains behind me. My heart began to jump when I sat the first orange beams light up the clouds. With each moment the light got warmer and slowly painted the scene from top to bottom. First, the clouds caught fire and then eventually the mountain began reflecting back that glorious warm glow. I kept shooting feverishly until the color began to fade. Success!

In the image below we see the “Ice” part of this post. I am at the same spot along the water’s edge, this time in late afternoon with the sun setting behind the mountain in our view. This time the clouds were a bit too dense to light up dramatically with the sunbeams. For this image, I used a very long exposure (90 seconds) to allow the clouds to move across the sky and smooth out the surface of the water of the lake. The tone and color of the image couldn’t be more opposite than the sunrise shot. This shot is dark and brooding and feels and looks ice cold.

It is always fun to revisit a scene over and over to explore how the look, feel, and tone can change dramatically with the time of day. With the change in weather. With the change in seasons. At any given moment Mother Nature offers the proverbial box of chocolate with each scene — you are never sure what delight you will get.

Until next month…..m

Nikon Z9, Nikon 17-35 mm (@17 mm), f/11, 1/5 sec, ISO 64