28

Shot of the Month – February 2022

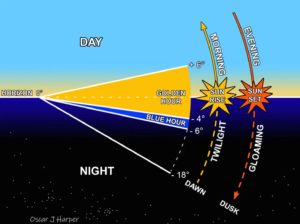

If you have any nature photographer friends you may have heard them talk wistfully about the “Golden Hour.” It is that special time of day just after sunrise or just before sunset when the light takes on magical hues of red, orange, or yellow and has a certain softness that seems to gently caress whatever it falls upon. During “Magic Hour” the sun is low in the sky, only a few degrees from the horizon.

The lesser-known cousin of Golden Hour is Blue Hour. I kid you not – it really is a thing. To explain it I have to get a bit astronomical-like, so strap in. And, uh, bring along your protractor…

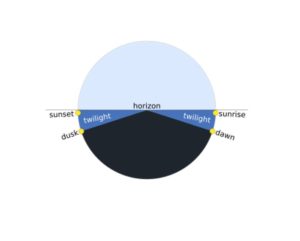

At its simplest, Blue Hour takes place during twilight. I have heard this term my whole life but what exactly does it mean??

Twilight is the time between day and night when there is light outside, but the sun is below the horizon. During this period the light we see does not come directly from the sun but rather is scattered and refracted from the upper atmosphere down to our eyes.

Now for the more complicated version. Time to break out those protractors (And see, you thought that box in your attic from 3rd grade wouldn’t come in handy. Tsk. Tsk.)

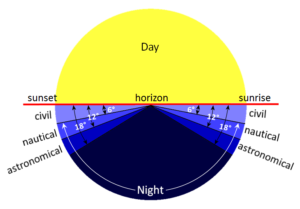

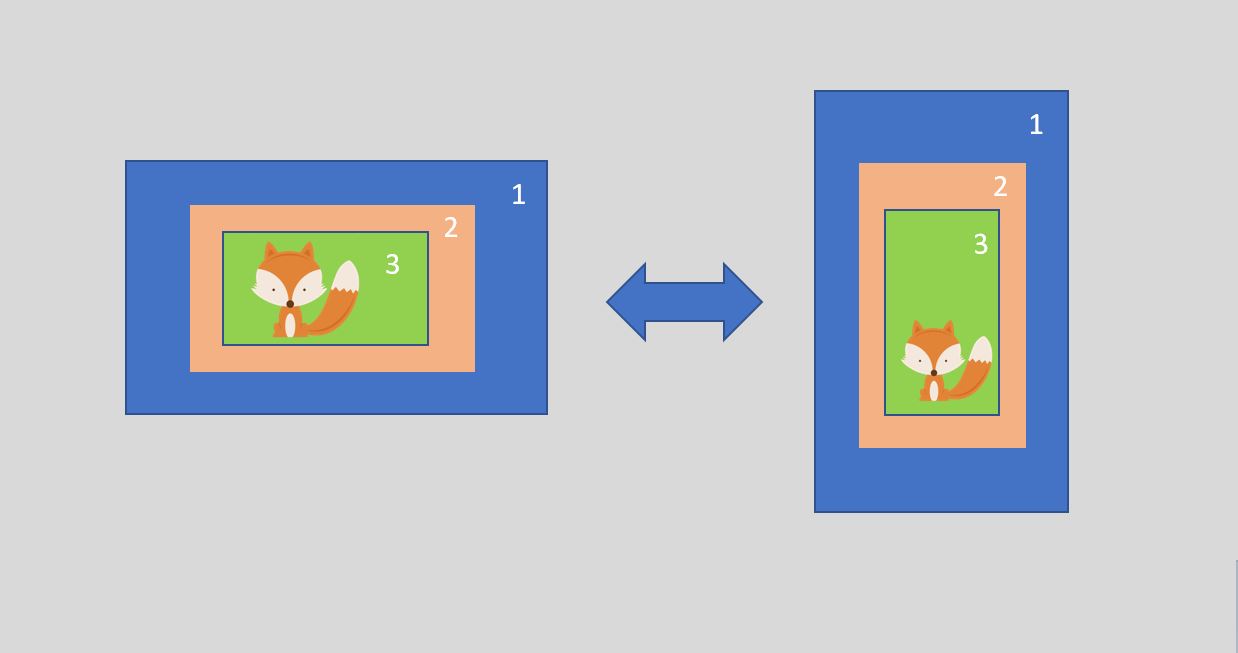

Astronomers were not satisfied with just one “twilight” and created a more precise delineation as shown here:

Let’s break it down.

Astronomical Twilight: The sun is located 12 to 18 degrees below the horizon. In astronomical twilight, sky illumination is so faint that most casual observers would regard the sky as fully dark, especially under urban or suburban light pollution. During astronomical twilight, the horizon is not discernible, and moderately faint stars or planets can be observed with the naked eye under a non-light-polluted sky. In the evening, when the sun is at 18 degrees below the horizon we have Dusk, the end of twilight, and the beginning of full evening darkness. In the morning, when the sun is 18 degrees below the horizon, we have Dawn, marking the end of full darkness as we begin the morning twilight.

Nautical Twilight: The sun is 6 to 12 degrees below the horizon. In general, the term nautical twilight refers to sailors being able to take reliable readings via well-known stars because the horizon is still visible, even under moonless conditions.

Civil Twilight: The sun is located less than 6 degrees below the horizon. Civil twilight is the period when enough natural light remains that artificial light is not (usually) needed.

Still with me? You are probably thinking – “Ok Galileo, this is all mildly (barely) interesting, but where the heck does Blue Hour fit in all this?”

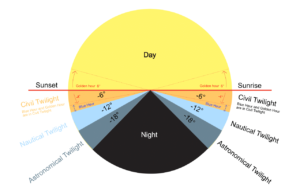

Here ya go:

Blue Hour takes place when the sun is between 4 to 6 degrees below the horizon which is usually about 30-40 minutes after sunset/before sunrise. During this period the light takes on deep shades of blue and can produce unique images. Truth be told the Blue Hour really only lasts about 20 minutes but the duration varies by where you are on the planet.

I like this graphic also (some may find this one clearer):

(Did you notice “Gloaming” in the graphic above? It is just an Old English/Scottish term for twilight)

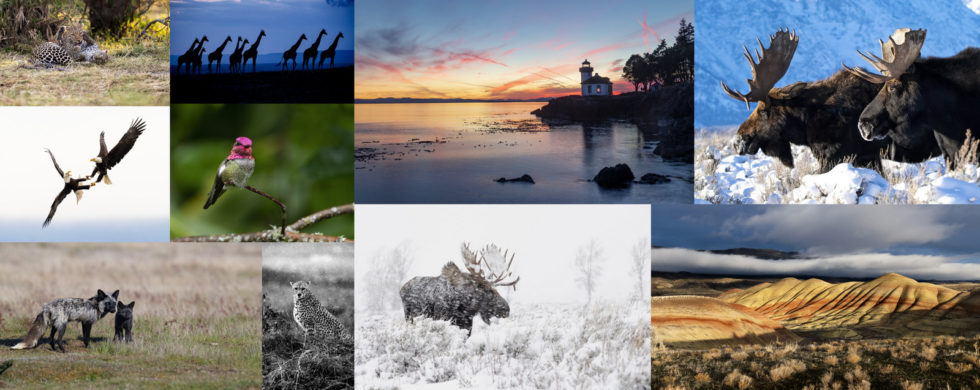

So that was a lot of blah blah to talk about the Blue Hour — more importantly, here is some of the magic it can work:

In this image we have a herd of giraffes strolling by shortly after the sun has set on the Serengeti plains of Africa (Masia Mara National Reserve in Kenya, to be precise).

Here is what the scene looked like while the sun was still above the horizon (late golden hour):

So, if you want to get your blue on you have to get out there waay early or stick around waay late, and then you have to work fast because blue time flies especially fast.

Now, don’t be blue, but we have reached the twilight of this post.

Until next month…..michael

Sources:

Mr. Reid.org (dawn-dusk-sunrise-sunset-and twilight)

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm, f/4, 1/400 sec, ISO 2000, -0.5 EV