31

Shot of the Month – May 2022

This month I share an image of a lovely Black-shouldered Kite (BSK). I photographed this beauty during a downpour in Masai Mara NP in Kenya (if you look closely you can see the rain coming down). The BSK gets its name from the dark shoulder patches on its wings and it is the contrast of those dark wings against the white underbelly that first caught my eye. But as I looked more closely at this bird hunkered down in the rain, I noticed that the head and back are draped in exquisitely blended gradients of gray. To add a bit more flair the BSK has striking yellow feet, a yellow beak, and dramatic red eyes.

Yes, I am smitten with this little raptor.

So let’s get our terminology in order. A bird of prey is called a raptor. A raptor is a bird that mainly uses its claws (talons) to seize prey. But what makes a Kite a Kite?

For you science types, Kites are birds found in three subfamilies (Milvinae, Elaninae, and Perninae) of the family Accipitridae. There are about 25 species of Kites found around the world. Y-e-e-e-aaaah, that’s not super helpful – got anything else?

Here’s what I could find:

- Kites, as a group tend to have weak legs so they like to spend most of their time in the air. In flight, kites often flap their wings once and glide for long distances before flapping their wings again. While gliding, the wings are tucked behind the bird to create minimal air resistance so the bird seems to float through the air.

- Kites typically have long, narrow wings and tails.

- Kites often have forked tails. (The BSK has a square tail, so there are exceptions)

- Kites have small heads and short beaks. The face of many kites is partly bare as many of them feed on carrion and the bare flesh makes cleanup easier.

The BSK prefers open land and semi-deserts in Sub-Saharan Africa and tropical Asia, and for some reason, they can also be found in Spain and Portugal.

This small raptor tends to dine on rodents, grasshoppers, crickets, lizards, and sometimes on injured birds, small snakes, and frogs. The BSK is about 12-15 inches (30-36 cm) in length, with a 30-36 inch (76-91 cm) wingspan, and only weighs about 7-12 ounces (200-350 grams).

When hunting the BSK sometimes hovers over a field looking for prey (similar to what kingfishers do over water). Other times the bird will fly slowly, close to the ground in search of a meal. And yet other times the BSK will sit on a perch scanning the ground for prey – once spotted the bird will dive down to scoop up the unsuspecting victim.

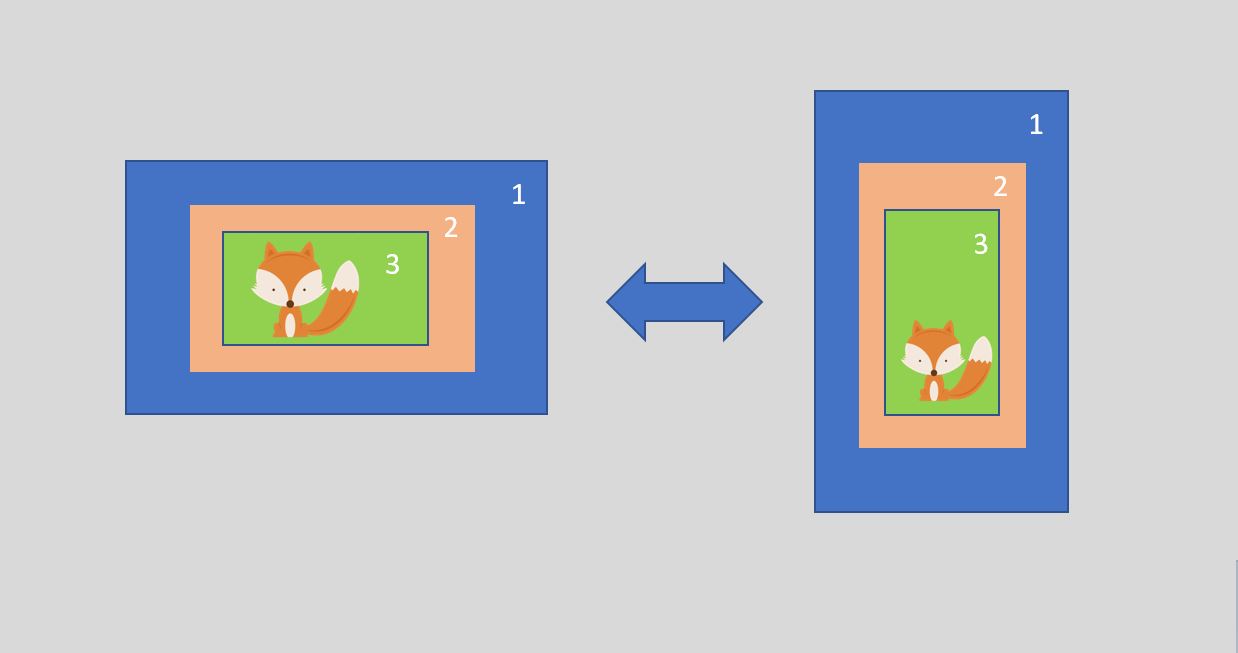

As for the photo, as mentioned earlier, I love the look of this gorgeous raptor. I shot with a wide-open aperture to cause the background to disappear into a quiet blur and allow the bird to really pop out of the image.

In the image above I zoomed in to create a nice portrait of just one BSK. Actually, there were three birds sitting on a dead tree as they waited out the rain together (our portrait guy is on the right):

The two birds on the left are flapping their wings to shake the rain off.

While in Kenya we spent most of our time focused on finding the big cats – lions, leopards, and cheetah. And boy oh boy, we found a bunch of them. We had amazing sightings of said cats every day. And despite all that I have to say that sitting with this wee raptor, as the rain gently plopped, plopped, plopped on the canvas roof of our land cruiser, is still one of my favorite memories from the entire trip. I had never seen a BSK up close before (via my powerful lens) and it was a wonderful revelation.

Until next month….michael

Here is a fun video of a Black-shouldered Kite hovering (watch how the head barely moves!)

Sources:

All Things Nature (What is the Bird called a Kite?)

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 1100, EV +1.0