Shot of the Month – November 2022

Pink Salmon (female) Fleeing from a Brown Bear (Katmai NP)

WoW! Look at that amazing animal. The power it has is mind-boggling.

Oh yeah, and that brown bear in the background is pretty impressive also.

bdbdbdbdbbdbdbd-Whaaaat?

Yep, I am actually, talking about the fish. Look, brown bears are impressive and all, but Pacific Salmon (Oncorhynchus) attain an entirely different level of amazingness.

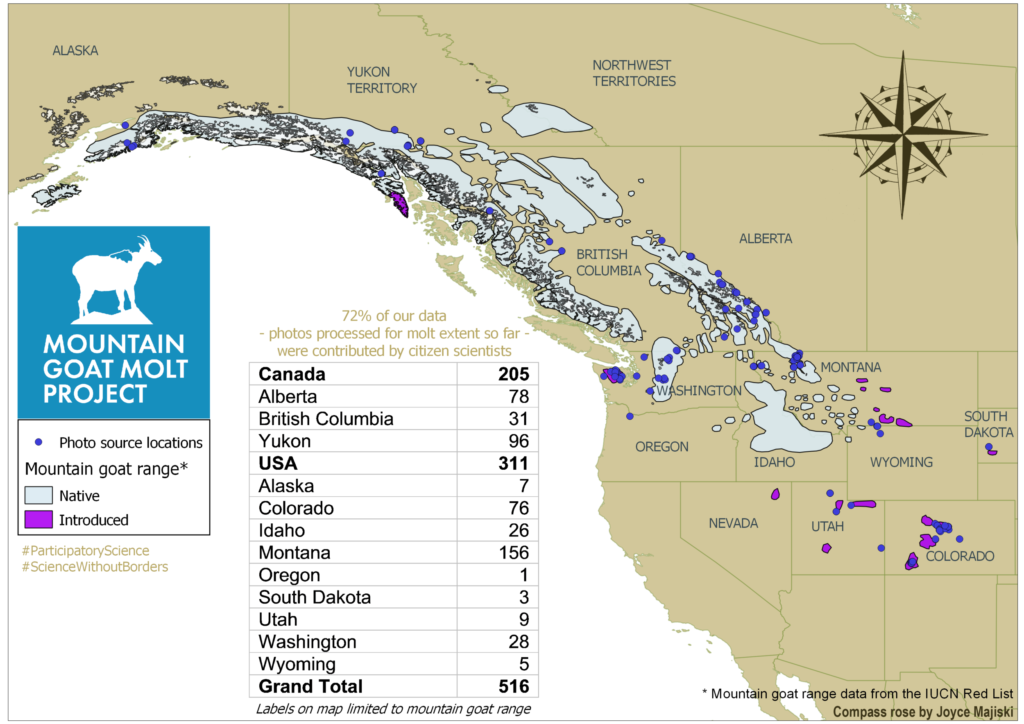

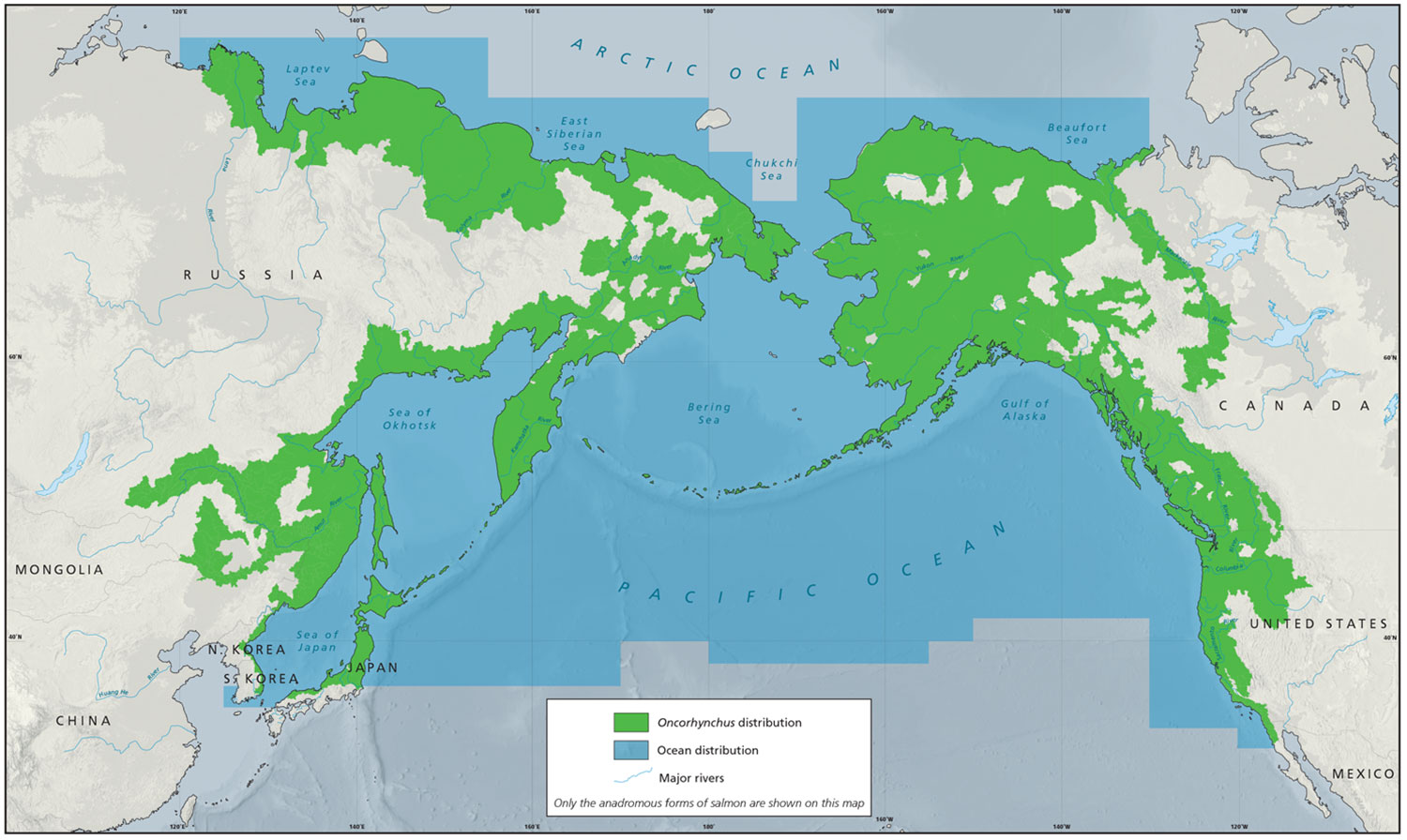

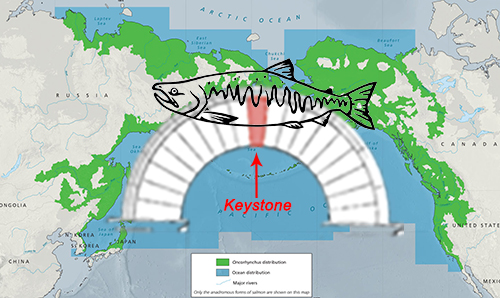

Despite their diminutive size, at least compared to a brown bear, the Pacific Salmon drives the survival of entire ecosystems across the northern Pacific Ocean as shown in this map below.

Stop for a second and let the scale of that sink in. This includes ecosystems found across thousands of miles from South Korea to Japan to Russia, across the Aleutians, and down the coastline of Alaska, Canada, Washington, and California.

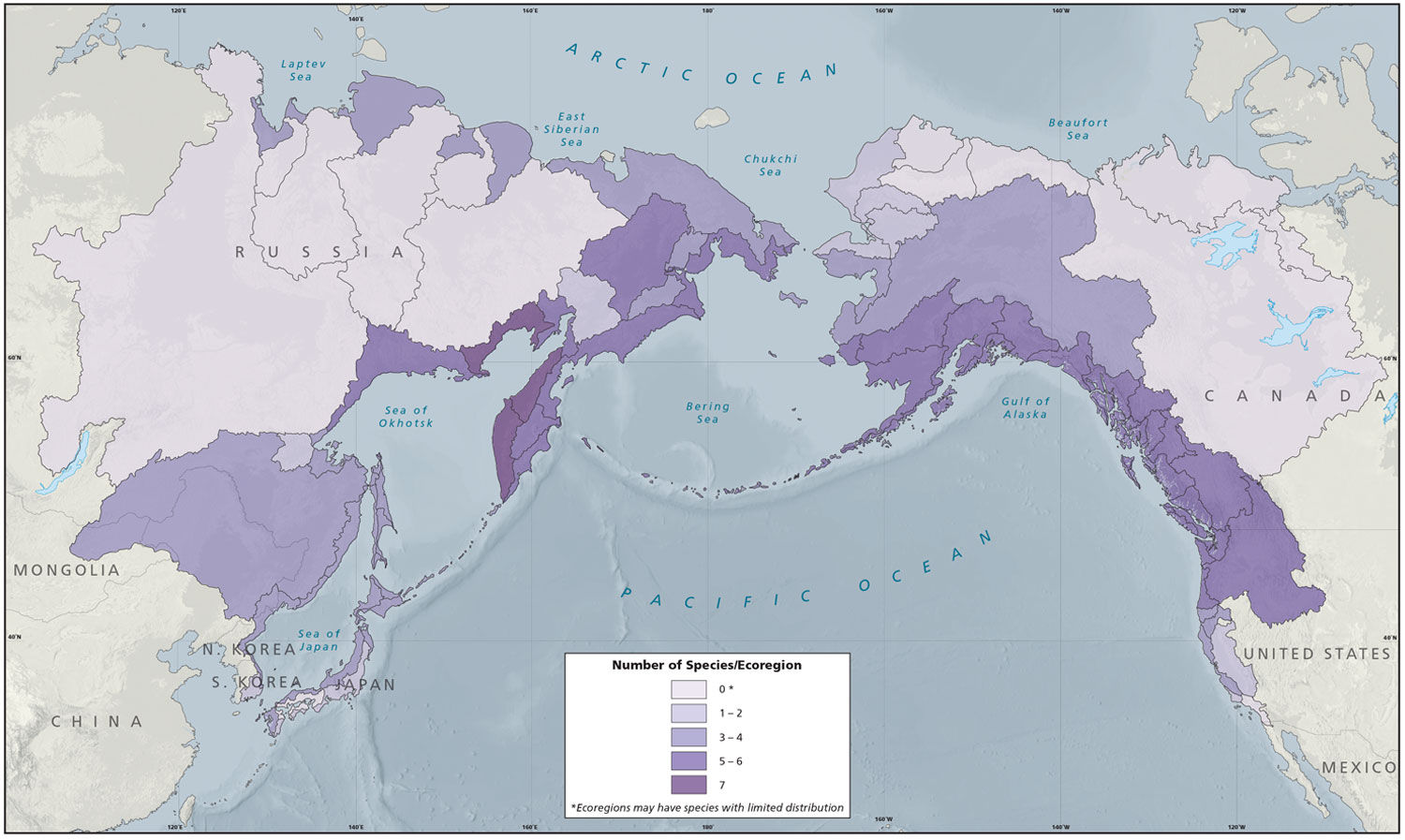

There are seven species of Pacific Salmon. Five of them are found in North American waters: chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, and pink. The other two species, masu and amago are only found in Asia. The seven species use the entire Pacific Rim coastline and can venture hundreds of miles inland in every direction from South Korea to Southern California. The coastal areas of the Sea of Okhotsk are the only regions to host all seven species as shown below.

Pacific Salmon impact so many ecosystems because of their anadromous lifestyle. Anadromous fish:

- Live the first years of their life in freshwater.

- Migrate to the ocean where food is more abundant, and then

- Return years later as adults to the same streams, where they were born, to spawn and die.

Phase 1: Freshwater to the Ocean

Pacific salmon are born in freshwater rivers and streams, and then as young fish, they begin their journey to the ocean. On this trek, more than 50% of the young salmon’s diet is insects that fall from the surrounding trees. Without the salmon there would be an explosion of insects to deal with. Salmon are the main predator of insects in aquatic environments and for this little feat alone they are Superstars. But there is more.

Phase 2: Ocean Life

Salmon gain a tremendous amount of mass while living in the rich ocean environment. As they gain mass, salmon play a vital role in the survival of key ocean species. For example, the Chinook salmon is the primary prey of the southern resident killer whale. Other ocean predators include seals, sea lions, porpoises, sharks, and lampreys to name a few. There is still more.

Phase 3: Return to Fresh Water Streams

Pacific Salmon spend 1 to 5 years in the ocean, depending on the species, before migrating back to fresh water. Each summer millions of Pacific Salmon migrate back to the streams, where they were born, to spawn and then die. The fish bring millions of pounds of nutrients from the nutrient-rich marine environment to the nutrient-poor river ecosystems. The salmon migration helps replenish the entire ecosystem, from the animals that eat the salmon, to the decomposers who break down their dead bodies, to the trees that grow from their broken-down nutrients.

Everybody is looking for a Salmon Meal

For example, over 137 species of fish and wildlife depend on the Pacific salmon for survival. Of this list, 41 species of mammals rely on the salmon including orcas, brown bears, black bears, wolves, river otters and so many more. Over 89 bird species feast on salmon including bald eagles, Caspian terns, and grebes amongst others. Predators feast upon the salmon, their eggs, their carcasses, or on their young. Over millions of years, many predators have adapted their movement and behavior to take full advantage of the annual salmon migration.

In areas rich with salmon, bears will eat an average of 15 salmon/day — a significant portion of their diet. Coastal bears get 33-94% of their annual protein from the salmon. In the upper reaches of the Chilkat River in Alaska, the return of half a million chum salmon attracts thousands of bald eagles to the feast. It is one of the largest concentrations of bald eagles in the world. Wolves normally hunt for deer, but once the salmon runs start, they shift their focus to salmon. In some areas, salmon represent more than 50% of the diet of wolves.

When salmon die their carcasses provide valuable nutrients to streams and rivers.  The significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean and released to inland aquatic ecosystems. The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide significant support for invertebrates and breeding waterbirds.

The significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean and released to inland aquatic ecosystems. The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide significant support for invertebrates and breeding waterbirds.

Bears play an important role in transferring nutrients from the coast and rivers to the woodlands and forests. The bears capture salmon and feed on carcasses, and often carry them into adjacent wooded areas. There they deposit nutrient-rich urine and feces and partially eaten carcasses. Bears are estimated to leave up to half the salmon they harvest on the forest floor, in densities that can reach 4,000 kilograms per hectare, providing as much as 24% of the total nitrogen available to the woodlands. The foliage of spruce trees up to 500 m (1,600 ft) from a stream where grizzlies fish salmon have been found to contain nitrogen originating from fished salmon.

The main reason that Pacific Salmon die after spawning is to give their offspring the best chance for survival. As mentioned previously, woodland river systems along the Pacific Ocean are nutrient-poor. The rotting carcasses of the adult salmon are a major source of food for the baby fish and give them the best chance at survival. One research study showed that 40-60% of the stomach contents of young salmon could be traced to salmon carcasses. (Ewww, but, amazing)

Brown Bear Cub Getting a Nutritious Salmon Snack

Throughout their life cycle, salmon f-u-n-d-a-m-e-n-t-a-l-l-y transform the way ecosystems function. As predator, they keep insect populations in check. As prey, they provide essential nutrients to mammals, fish, birds, reptiles across the entire northern Pacific Rim. In death, they transfer key nutrients from the sea to inland woods needed by their offspring. But they also provide the essential chemicals that are the building blocks of entire habitats of wetlands and forests.

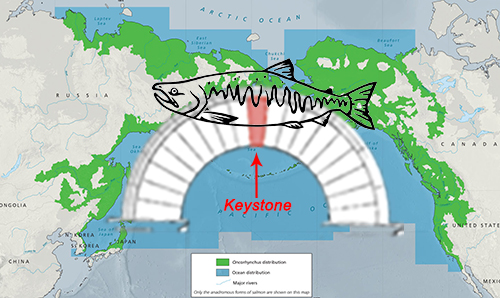

Because of all this awesomeness, Pacific Salmon are considered a KEYSTONE SPECIES.

Named for an architectural term—the keystone is the topmost stone in an arch that holds the entire structure together—keystone species are defined as species that have a disproportionately large effect on the communities in which they occur. They help maintain biodiversity and there are no other species in the ecosystem that can serve their same function. Without them, their ecosystem would change dramatically or could even cease to exist. (source)

This can’t be overstated – without Pacific salmon, many species, and entire ecosystems, are at risk for failure. We are seeing salmon populations drop in many locations, due to pollution, dams, logging, over-fishing, disease, etc. We are also seeing almost immediate ripple effects. The decline of the chinook salmon population is a major reason that the southern resident killer whale is now listed as critically endangered (only 76 individuals remain in the wild). In the US Northwest the declining salmon population is causing great stress on the populations of bald eagles, brown bears, grizzly bears, black bears, osprey, harlequin duck, Caspian tern, and river otter. To name a few. The salmon disappeared in McDonald Creek in Glacier National Park in 1981, and the bald eagle population plummeted from 600 to 25 in less than a decade. Today, salmon are extinct in almost 40 percent of the rivers where they were known to exist in California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Wild Salmon have declined by 90% in Washington, Oregon, and California. Hundreds of salmon runs have collapsed across the Pacific Rim.

Normally, this is where I would end with a pithy wordplay, or a bad pun, but this situation is too serious to joke about. We need the Pacific Salmon to thrive. It is not lost on me that the coastline of the northern Pacific Rim is shaped like an arch. The keystone of that arch is crumbling. Let’s hope that humanity can act quickly to protect this Superfish.

If you want to learn more and see how you can help, check out these links:

Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition

Wild Salmon Center

Patagonia Provisions

Thanks…until next month…..michael

Nikon Z9, Nikon 80-400mm (@ 260mm), f/5.6, 1/1000, ISO 900

Sources

Ecosystem Keystone: Salmon Support 137 Other Species

Pacific Salmon (Wild Salmon Center)

Salmon: a keystone species (PacificWild)

Nature up close: Salmon, a keystone species in the Pacific Northwest (CBS News)

Salmon in Food Web (ScienceWorld)

Salmon Run (Wikipedia)