31

Shot of the Month – May 2023

Brace yourself, Sheila…. (scroll down veery slowly….and best viewed on a large screen)

Ok, I still wasn’t ready. Wow.

For the uninitiated, that is an extreme close-up of a Southern Ground Hornbill (SGH). I photographed this fellow in Kenya. To be fair, how many of us would pass the extreme close-up test??

(If you are viewing on small screen you will definitely want to zoom in to really appreciate the full effect)

The SGH is one of my FAVORITE creatures on the planet. Every sighting of these birds is an absolute delight.

Lets run through what makes them so special:

Killer Looks

There is no denying that these birds are striking in their appearance. The SGH is a large bird (wild turkey size for quick comparison) that can stand 4 feet tall (1.2 m), weigh up to 15 pounds (6.8 kg) and he definitely draws attention with his dramatic markings. The male’s face and throat is adorned in bright red and he can inflate that neck wattle to attract the females. The female looks similar though her neck wattle will have a violet blue patch for easy identification.

And did you notice those sumptuous eyelashes? Those are actually modified feathers!! They are used to protect the bird’s eyes from dust and sunlight.

Of course the other key defining feature of the SGH is that massive, slightly curved hornbill. It is an effective tool for foraging and capturing prey.

A good view of the SGH’s hornbill:

Just a stunning looking creature!

Amazing Sound

The males can use that large wattle to create a booming call that can be so loud that it can be mistaken for a lion’s roar and can be heard almost 2 miles (3 km) away. The large bump on the bird’s bill is a chamber that is used to amplify their calls. He basically has a built in boom box.

Click on this video to hear a small sample of one of their wonderful calls (Link here):

(Did you notice the lovely blue patch on the female on the left?)

Chill Vibe

SGHs live in groups of 2-12 individuals led by a dominant mating pair. The group spends most of their day walking slowly in search of food. These guys are just so cool and ganster as they come strolling by on the savannah. SGHs can fly and they roost in trees at night but they prefer sauntering and can cover up to 7 miles/day. (11 km/day).

These birds are carnivorous and will eat just about anything they can catch and fit down their throat. Prey include insects, frogs, toads, lizards, snakes and tortoises. SGHs will also hunt hares, rats, squirrels and even small monkeys. Once in Botswana I saw a crew come through a field and they were just destroying the small wildlife. Peck, there goes a spider. A few steps later, BAM, caught a lizard. A few more steps, POOF, caught a grasshopper…..they were relentless.

Many years ago I witnessed an epic battle between a SGH and a frog. You can read about it here.

A SGH tossing back a spider snack

Fascinating Family Life

Scientist describe the SGH as an “obligate cooperative breeder.” Scientists really know how to suck the romance out of something. So what does that mean??

A SGH family group is made up of a dominant male and female while the rest of the group members are typically younger males from previous clutches. The “helpers” support the mating pair in raising the chicks and will hunt, help take care of the young, and do much of the “work” of the flock. Female offspring may stay with the parents for only a few years as only one adult female is tolerated in a group and breeding is strictly between the breeding pair.

Experiments in captivity indicate that birds without at least 6 years experience as assistants rarely breed successfully if they do become breeders!! And studies show that if assistants are not present, adult SGH often fail to breed successfully.

At Risk

Sadly the SGH is struggling to survive and the species is listed as vulnerable to extinction globally. In South Africa, Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland the bird is listed as endangered. The bird is also found in Angola, Rwanda, Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It is estimated that only 3,000 birds remain in the wild and numbers are dropping in most countries.

The primary threat to the SGH is loss and fragmentation of habitat as humans expand their footprint into wild areas. Hunting and poisoning of SGHs is a growing problem.

Another key issue is that the SGH is one of the slowest reproducing birds in the world. The SGH has an unusually long life span – up to 50 years in the wild and up to 70 years in captivity. However, these birds often do not reach sexual maturity until 4-6 years old and may not start breeding until 10 years old.

Although the female usually lays more than one egg, only one chick will survive more than a few days. The parents will ignore the younger siblings even when food is abundant. Scientists hypothesise that the other eggs are “insurance” in case the first egg does not hatch.

This lone chick matures slowly and is dependent on the parents for at least 2 years. Put this all together and a SGH group typically only produces and raises one new offspring every three years. This makes it difficult for the SGH to increase population numbers while under growing threats.

Somewhat encouragingly there are a wide range of conservation efforts now underway in many countries. Some groups focus on growing support to stop hunting and persecution of the birds. In other places scientists are collecting the 2nd chick from the nest before it dies. The scientists raise the chick and then reintroduce it into the wild.

Fingers crossed that we will have these wonderful, charismatic birds galavanting across the savannah for many generations to come….

Until next month….m

Sources

Africa Geographic – Southern Ground-Hornbill

Worldland Trust – Southern Ground Hornbill

Africafreak – Southern ground hornbill facts – Lifespan, habitat & diet

National Geographic – Southern Hornbill

Wikipedia – Southern Ground Hornbill

Nikon D5, 600mm f/5.6, 1/1500 sec, ISO 2000,

30

Shot of the Month – April 2023

The Pacific Northwest (PNW) is chock full of “must-see” natural wonders and unique landscapes. A few that I have seen so far:

Mount Rainer and the nearby Reflection Lake

Peter Iredale Shipwreck (Sunset) (Visit at Sunrise)

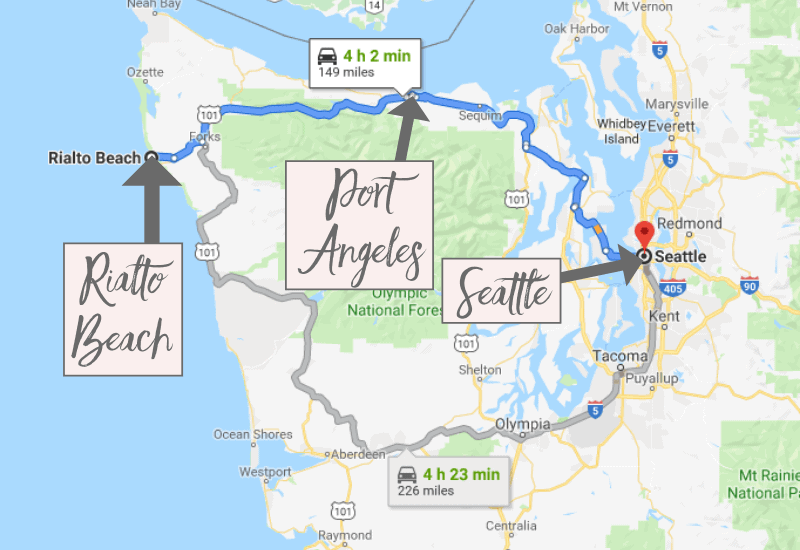

And this month we visit Washington State’s iconic Rialto Beach (RB). RB is a public beach found in the Olympic National Park, about 14 miles from the town of Forks (For Twilight fans, yes, it is THAT Forks). This map gives a good sense of the location:

(Map Source)

Most visitors walk north from the parking area for about 1 1/2 miles to reach the dramatic looking sea stacks that you see in my image above. The hike along the beach is lovely as you pass massive fallen trees and endless driftwood strewn about the coastline. If the tide is low you can also explore the tiny worlds found in the tide pools:

Just past the sea stacks erosion has created the “Hole-in-the-Wall” in a large rock that allows you to look back at the sea stacks:

Given that RB is on the West Coast the most dramatic shots are usually taken at sunset. However sunrise can offer nice scenes when the conditions are right:

At midday the light is usualy too harsh to get a nice shot but converting to B&W can help:

A sunset scene with a splash of color

Looking to get your “beach on” while visiting the PNW? Put Rialto beach at the top of your list for some great hikes, wildlife (I have seen otters near the sea stacks), outdoor camping (permits available), tide-pooling, and of course, the potential for great photography.

Pro tip: Ideal conditions will be at low tide, near sunset. Hole-in-the-Wall and tidal pools are only accessible near low tide conditions. High tide can push you off the beach and close to the massive drift wood which can be tricky to navigate/climb over. There is a hiking trail in the adjecent forest so you can still reach the sea stacks at high tide but other options will be limited.

Some good pointers on visiting Rialto Beach:

Hiking Rialto Beach to Hole in the Wall in Olympic National Park

The Ultimate Guide to Rialto Beach and The Hole In The Wall Washington

10 Best Things To Do at Rialto Beach

Until next month…m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 17-35 mm (@ 17mm), f/13, 1 sec, ISO 100,

31

Shot of the Month – March 2023

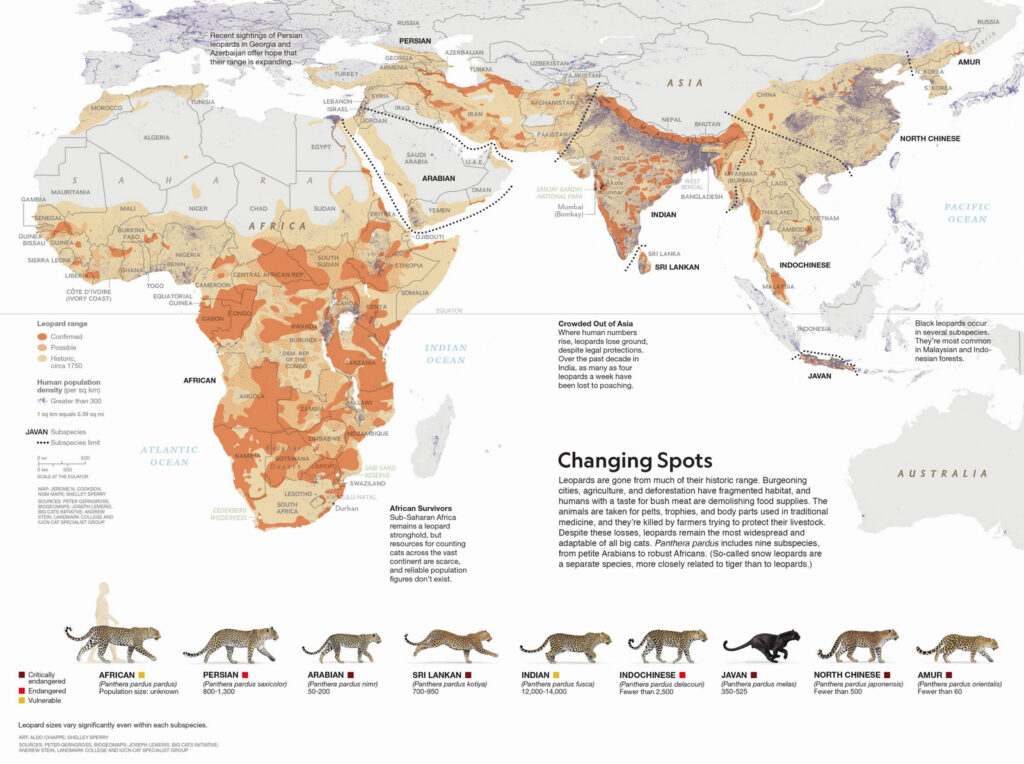

I love wild cats and I have had the good fortune of seeing lion, tiger, cheetah, serval, caracal, and the African wildcat in the wild. Of that group I am particulary partial to the leopard. Pound for pound they are perhaps the strongest of the group. Leopards are incredibly elusive and even a single sighting on a safari is a major victory. On our trip to Kenya in 2021 we had the amazing good fortune to have six leopard sightings!! I have only seen leopards in Africa but there are actualy 9 subspecies of leopard spread out across the world:

It is generally accepted that the African leopard is the most numerous species though there is no reliable estimate of their total population on the continent. India is home to roughly 12,000 leopards. Many of the other species of leopards are on the verge of extinction, however.

Individuals remaining:

Amur Leopard: 100

Javan Leopard: 250

Arabian Leopard: 200

Sri Lankan Leopard: 800

Persian Leopard: 800

Indochinese Leopard: 1000 to 2500

Leopards are stealth hunters and are renowned for their ability to carry prey up into trees to feed in peace. In the image above we found a leopard in the Masai Mara National Reserve with the remains of a Thompson’s Gazelle.

The uninitiated sometimes confuse the leopard with a cheetah. As you can see here however, the animals are quite different in size and build:

The leopard has shorter legs and a more muscular build. The cheetah (also photgraphed on the same trip) is built like a greyhound dog – long legs and a lean body. The spots on the cheetah are solid while the leopard has not spots, but rosettes. The cheetah is built to chase small prey across the open plain while the cheetah stalks in the bushes or may pounce from above while hiding in a tree.

A few more images from our trip:

A mother leopard playing with her cub just after sunrise

Another leopard with a Thomspon gazelle:

Kitty in a tree:

We found this female hunting along a riverbed just after sunrise

The color version:

The stunning leopard – its elusive magic never fails to dazzle.

Until next month….m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, f/4 1/500 sec, ISO 250, EV +1.33

28

Shot of the Month – February 2023

If you spend much time with Bald Eagles you quickly learn that they are quite the thieving sort. In spite of their majestic, regal looks, Bald Eagles are often gangsters in fine dress.

Check out my post, Thug Life, for more info on their wicked ways.

Even when food seems plentiful Bald Eagles will attack each other relentlessly to steal food which seems counterintuitive. Why risk injury attacking another very well-armed eagle when there is so much food available?

Armed and dangerous:

Each summer Bald Eagles congregate along the Washington coast where midshipman fish are spawning. The concentration of fish can attract dozens of eagles which then can attract dozens of photographers, like me. And each summer us photographers ask the same question over and over as we watch another eagle fight or after we see one theft attempt after another.

“Why do they do this when there are soooo many fish right in front of us”?

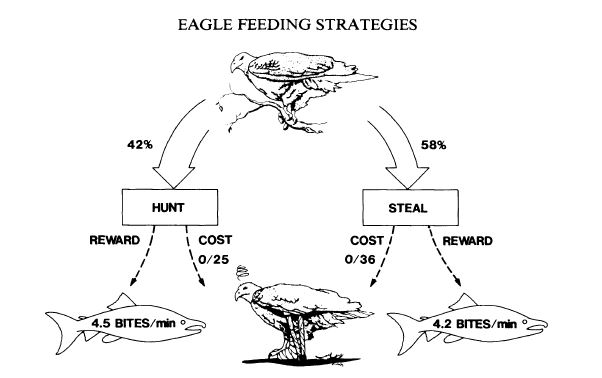

Seems that scientists have noticed the perplexing behavior also and have been trying to solve this mystery. I found a paper, “Fighting Behavior in Bald Eagles: A Test of Game Theory,” by Andrew J Hansen that was published in 1986 where the scientists studied Bald Eagles at a site in Alaska.

Some key findings (at least from this one study):

- Catching Fish = Stealing Fish

Seems that eagles that stole fish from others ate as well as eagles that caught their own fish:

Here we have an eagle catching his own fish:

2. Risk for Injury is Low

The scientists witnessed numerous attacks between bald eagles as one tried to steal from another. Surprisingly, during the study period, they witnessed zero injuries between the eagles. Despite the dramatic action the encounters rarely escalated to serious fights that can cause injury.

Eagles apparently use an array of postures, gestures and vocalizations to demonstrate both their willingness and ability to fight. Larger eagles tended to steal more often as it was clear that they were the stronger combatant. The smaller eagle would quickly acquiesce to the larger opponent and larger birds won 85% of the time.

3. Position matters:

Position was also important – a bird on the ground was always at a disadvantage to a bird coming from above in the air.

Whether a bird is positioned above or below an opponent would seem to affect it chances of winning because talons serve as the primary weapons. An aerial attacker has its feet in a position to threaten a feeder on the ground.

In the image below, the eagle on the left was sitting on the ground – at a clear disadvantage. In this encounter he leapt up to confront the attacker but as their talons interlocked the bird on the right had much more momentum and was able to flip the ground-based eagle over.

4. Communication is Important

By carefully understanding the intentions of each other, eagle interactions rarely escalate into serious battles that can lead to injury or death. Eagles will indicate their hunger level through ritualized displays. For example, in the image below we see an eagle that has thrown her head back and is vocalizing loudly — this is one of several displays that eagles can use to clearly proclaim “I am very hungry, don’t get in my way.”

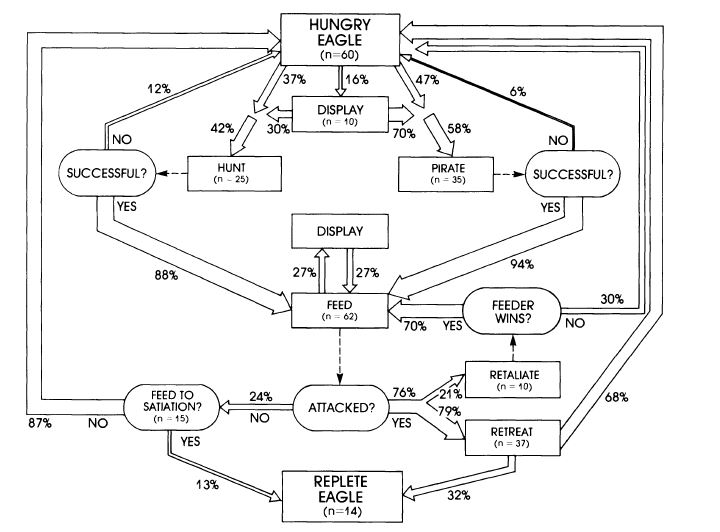

The hungrier the bird, the more she will display. Other birds will see this and take this into account before deciding to attack. Or, if this bird would then go on the attack, other birds would know that she was very hungry and therefore, more motivated to fight so they might give up their meal more readily.

Fascinatingly, by throwing the head back, the eagle allows other birds to see how full his/her crop is. Another ingenious non-verbal message: “Hey, my crop is empty and I want that fish more than you do.” (A bird’s crop is an expandable “muscular pouch near the gullet or throat.” It is used to store excess food for later digestion.)

The value of a prey item to each player varies with hunger level. A bird with a crop that is nearly full can derive less benefit from a salmon than can one with an empty crop. Relative hunger level may be discernable from crop size or the length of time a bird has been eating.

Eagles apparently assessed the relative attributes of conspecifics and often chose to displace the individuals most likely to yield (small or replete birds). Pirates sometimes appeared to evaluate feeders quickly while flying overhead. Other times the birds landed and seemed to study feeders intently before attacking. The latter method may allow more accurate assessment but it is done with loss of a possible positional advantage enjoyed by aerial attackers.

At any given moment the eagles are constantly assessing size (Am I bigger?), position (birds in the air have tactical advantage over birds on the ground); and hunger level (who wants this more, me or her?) before attacking or if deciding if they should give up their fish.

This fascinating diagram from the study attempts to map out the parameters at play:

I love the scientific insights but I love photography even more. In my first image above we see an aerial attack and some nifty flying as the eagle with the fish implements a barrel roll to confront his attacker.

Here we see the same attack, just a fraction of second sooner:

Everybody wants in on this fish:

An adult Bald Eagle harassing a juvenile Bald Eagle (The adult successfully stole the fish!!).

It seems that Bald Eagles are not the reckless pirates I thought they were. Of course, I should have known better – animals are hyperaware of their surroundings and do not take unnecessary risks. Mother Nature is far too wise for that. Each Bald Eagle is constantly evaluating its best solution for finding a meal. Each bird uses a complex array of communication and observation to switch between the tactics of hunting or pirating, in a moment’s notice, depending on which approach is most favorable for the opportunity at hand.

Game on!

Until next month……m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), f/5.6, 1/1500 sec, ISO 400, EV +1.0