08

Time to look back at a few of my favorite images from 2019. These may not always be my “best” images from the year but they are special to me for various reasons that I will comment on below. In no special order:

1. Jaguar

Five of my favorite images for the year were captured during our November trip to the Pantanal in Brazil. Here we have a lovely female jaguar. You had me with that look, but with the crossed paws? I’m done….

2. Giant River Otter

Another shot from the Pantanal. With this shot I finally managed to get an image of a giant river otter doing what they do best — eat fish. Great eye contact from both the otter and the fish and I love how you can see how beautiful the armored catfish is. And this is one the few images where there was no obstruction — I have hundreds of images of otters with grass, sticks, leaves, etc. blocking the view. I shot this image on the LAST outing on the LAST day of the trip! You just never know…

3. Green Kingfisher

Continuing with images from the Pantanal. On this trip I managed to get two very nice images of kingfishers. Here is the first of a green kingfisher. I love the colors and that clean background. Such a gorgeous bird.

4. American Pygmy Kingfisher

I love the “other worldly” look of this image of the American Pygmy kingfisher — the 2nd really nice kingfisher shot that I got from the Pantanal this year. You might not imagine it, but photographing a tiny bird, on a moving boat is exhausting. Hundreds of images later, finally one that worked.

5. Toco Tucan

This is the last image on the list from the Pantanal trip. I just love the colors of this bird – amazing! Toucans are more common in southern Pantanal — we were in the north so getting an image of this incredible bird was totally unexpected. We only had two, very brief sightings during the entire trip and I was only able to fire off a few shots before the birds vanished each time. These birds never stopped moving, jumping from branch to branch, while trying to approach and shoot from a small moving boat – yikes! It was hard to even find the find the birds in the view finder let alone compose a good shot. Sometimes you get lucky…

6. Red Fox

The rest of the images are from the good ol’ USA. In 2019 I got my first worthwhile images of red foxes. Here we see a female bringing back a rabbit for her kits at the den. Yes this is a red fox – they have several color morphs that include black, brown, silver, etc.

7. Barn Owl

My first image of a barn owl!! This image was captured before sunrise. See more here.

8. Short-eared Owl

This image is bittersweet. Each winter I could count on seeing short-eared owls in this amazing habitat north of Seattle. But no longer – the fields were flooded over in 2019 to create a salmon habitat. (Was the same place I saw the barn owl).

9. Savannah Sparrow

In 2019 I managed to add a few images to my Sparrow/Tulip series. Savannah Sparrow in Yellow. You can see a red version here (4th image from the top).

10. Moose

In 2019 I made my first trip to Grand Teton NP and captured this lovely fall image of a moose. I plan to go back to the Grand Tetons this winter so hopefully we will see more images from this park on the 2020 list…

11. Ponytail Falls

I made a quick weekend trip to the Columbia River Gorge in Oregon in 2019 and came away with two nice shots. The first was this lovely autumn scene:

12. Wreck of the Peter Iredale

The other nice shot from that weekend was captured along the Oregon coast. In 1906 a steel ship called the Peter Iredale ran aground here. By sheer luck I was there on a day when the tide was low at sunset allowing me to shoot next to the wreck.

Have a favorite? Which one(s) do you like best?

I can’t wait to see what Mother Nature will share with me in 2020!

Happy New Year!

31

Shot of the Month – December 2019

In 2019 I visited the Pantanal in Brazil to photograph jaguars and other wildlife – you can see the highlights in this video. En route to the prime jaguar location we spent one night at small lodge where we saw another wild cat of the region – the Ocelot. Each night the lodge puts out chicken to attract this rarely seen cat. I am not a fan of baiting wildlife as it can diminish their survival skills and promote dangerous human – wildlife interaction. For what it is worth this cat does not show up every night and it seems that he is not dependent on this food supply but only drops in when he wants a supplement. Or perhaps only when he is in the mood for a bit of chicken….

As you can see Ocelots are fairly small, coming in at about twice the size of an average house cat or roughly the same size as a bobcat. The males can grow to about four feet in length while the females are usually about two and half feet long. Ocelots tend to weigh between 28-35 pounds.

These solitary cats are highly nocturnal and use their exceptional eyesight to hunt rabbits, rodents, snakes, fish, frogs, young deer, peccaries, iguanas and other lizards. They are good swimmers and good climbers so they will hunt for fish in nearby streams while also stalking monkeys and birds in the trees. Ocelots hunt by walking slowly along game trails hoping to ambush their prey. They are also “sit and wait” predators, sitting motionless for 30-60 minutes at a den or burrow site. If no luck they move quickly to another site and sit and wait again.

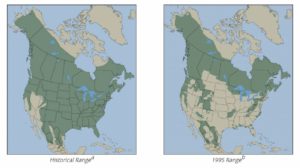

Ocelot Range Map (Source)

Ocelots can be found from southwestern United States to northern Argentina. These cats thrive where plant life is dense and can be found in tropical forests, thorn forests, mangrove swamps and savannas. There are about 800,000 to 1.5 million Ocelots remaining in the Western Hemisphere but their numbers are declining. In the US Ocelots were once found in southern Arizona and throughout much of Texas, and even reaching Arkansas and Louisiana. Alas, human development in these areas has caused Ocelot numbers to plummet and they are now at risk for extinction in the US. Today they can only be found in southern Texas with only about 40 individuals remaining. In Colombia, Argentina and parts of Brazil the cat is listed as vulnerable.

The fur trade in the 1960s and 1970s was devastating to the Ocelot population – in 1970 alone over 140,000 Ocelot skins were traded in the United States. Fortunately most countries now ban the trade of Ocelot skins. While the threats from the fur trade, hunting, and the pet trade have reduced other threats are growing. The loss of habitat and fragmentation of habitat is a major threat as us humans continue to expand our footprint across the planet. Traffic accidents are a growing threat as Ocelots are increasingly hit by cars as new roads crisscross their shrinking habitat. Logging and poaching of their prey species are additional threats to their survival.

Although these lovely cats are rarely seen our world would be much poorer without their nightly jaunts through the jungles of our dreams and fables. Let’s hope that we can find a way to allow the Ocelot to roam our jungles for many years to come.

Until next month….m

And for your easy viewing pleasure, our Pantanal Highlight Video (includes images of the Ocelot):

Sources:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 70-200mm (@ 95mm), f/2.8, 1/125 sec, ISO 6400

30

Shot of the Month – November 2019

While this ship is clearly no longer sea worthy its rusting hull can, at least for a few more years, take our imagination on a journey back in time. The hull, located on the beach at Fort Stevens Park, is all that is left of the Peter Iredale, a four-masted steel barque that ran aground on the Oregon coast on October 25, 1906. The ship had departed from Salina Cruz, Mexico (about 60 miles south of San Diego) a month earlier bound for Portland, Oregon with 1,000 tons of ballast and a crew of 27. Nearing the end of its journey the ship encountered a fierce storm just four miles south of the Columbia River channel and was driven onto the beach in the driving winds. The force of the impact was so great that 3 of the 4 masts of the ship snapped when it hit the sand. All crew were rescued from the ship and there were no casualties.

Above we can see the Peter Iredale in all his glory — the steel ship was built in 1890 in Maryport, England and was 285 feet long. The ship was sent to Portland to pick up a cargo of wheat that would be sailed to England. Below we can see the ship not long after it ran aground.

There was little damage to the hull so initially the plan was to tow the ship back to sea. However, the recovery team had to wait a few weeks for favorable weather and during this time the ship sank deeply into the sand and it was impossible to move it. And so there it has stayed for the last 113 years.

And, in case you were wondering:

Who the heck is Peter Iredale?

He is the bloke that owned the ship. He had a shipping firm called Iredale & Porter and was a business big shot in Liverpool, England.

Did the crew screw up and cause this mess?

Well, a naval inquiry was held by the British Vice-Consulate to determine the cause of the wreck. The British Naval Court ruled that the sudden wind shift and the strong current were responsible for the stranding of the ship, and that the captain and his officers were “in no wise to blame” and in fact the captain (Captain H. Lawrence) and the crew were commended for their attempts to save the ship.

I only spent one afternoon at the wreck site and as luck would have it, there was a low tide near sunset allowing me to walk right up to the hull. Here a few images from different perspectives and as the light transformed as the sun went down.

Here is a landscape orientation as some clouds rolled in:

As the sun nears the horizon the light weakens but there is a soft pink hue (alas, we lost most of those lovely clouds):

Here we can see the full side of the remaining hull in the last light:

On that fateful day, just before leaving the beach, it is reported that the red-bearded captain stood stiffly at attention, saluted his ship, and said:

May God bless you and may your bones bleach in these sands”

He then turned and addressed his men with a bottle of whisky in his hand. “Boys,” he said, “have a drink.”

I don’t know if this salty tale is all true, but I like to believe that it is.

Ayyye! Until next month….m

Sources:

Here is a fun video on the shipwreck:

And here you can see historic images of the wreck over the last 100 years:

https://www.oregonlive.com/travel/2018/03/watch_oregons_iconic_shipwreck.html

Nikon D850, Nikon 17-35mm (@ 17 mm), f/8, 1 sec, ISO 64. HDR composite of 5 exposures (-2,-1,0,+1,+2 EV).

31

Shot of the Month – October 2019

There are 114 species of kingfishers around the world and most are bright splashes of color with wings. These small to medium size birds tend to specialize in catching fish though a few prefer insects. All tend to have large heads, long, sharp pointed bills, short legs and stubby tails. One of the most common kingfishers is the Pied Kingfisher as seen above. Bright splash of color?? It seems that the Pied Kingfishers were at the back of the line when the colors were given out as they are rather penguin-esque decked out in their monochromatic black-and-white color scheme. Click here to see a more colorful variety.

As shown below, Pied Kingfishers are exceptional hoverers — by flapping their wings rapidly they can stay in one place for an extended period time as they scan below looking for fish in the water. They are actually the largest bird that can truly hover. While hovering they have to keep their head perfectly still to judge the location of the fish below. Here is a great video that explains the hunting technique of these skilled fliers. And another good video here.

A fresh kill captured on film….Definitely will NOT need a bigger boat for this one.

The Pied Kingfisher can be found throughout sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia from Turkey to India to China. I photographed this lovely chap in Kruger National Park in South Africa.

The Pied Kingfisher – what they lack in color they make up for it with true acrobatic talent and classic formal style and grace.

Until next month….m

Sources:

Nikon D500, Nikon 600 mm f/4 (@ f/5.6), 1/1500 sec, ISO 200, EV -0.5

30

Shot of the Month – September 2019

So what’s going on with this big ol’ male lion? Is he snarling? Is he about to sneeze? Did he get a whiff of a stinky warthog?

All good guesses, and thanks for playing along, but all incorrect.

What we got here is a good example of the flehmen response. Uhhhh, the flaming what?

The flehmen response — in German flehmen means to “bare the upper teeth.” Ok, that seem accurate, Simba here is indeed baring his upper teeth. So we got the “what,” how about the “why”?

Well, many animals exhibit this behavior to draw in air to reach a specialized organ above the roof of the mouth. This organ has specialized receptors to detect pheremones, scents and other chemicals. This organ is called the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson’s organ (Ludwig Jacobson described the organ in 1813, even though Frederick Ruysch found it first in 1732). The vomeronasal organ is connected directly to the brain and allows the animal to better assess potential prey animals, predators and potential mates. This process is distinct from smelling and engages a completely different pathway to the brain.

Some animals, like cats and horses have to raise their lips to allow air to reach this specialized sensor. Other animals, like elephants can access their vomeronasal organ without the lip curl (Thank You Very Much). Flehmen is demonstrated by most of Africa’s ungulates and predators including giraffe, rhinos, buffaloes, lion, leopards, cheetahs and other cats. Fun fact: Hippos can do the flehmen response underwater! Jacobson’s organ is also found in all snakes and lizards, dogs, cattle, pigs, and in some primates. Snakes use the organ to sense prey — they stick their tongue out to collect scents and then touch their tongue to the opening of the organ when the tongue is retracted. Humans do not have this specialized organ. Both males and females can demonstrate the flehmen response. For example female sable antelope use flehmen behavior to allow them to synchronize conception and birth of their offspring in a herd.

The male lion above, photographed in Kruger National Park in South Africa, wrinkled up his nose after his lady friend walked over to say “Hi.”

And she gave him a friendly head nuzzle:

After this the male stood up and checked to see if “love was in the air.” For the non-romantics: He triggered the flehmen response to draw in air to see if the female was emitting pheremones that would indicate that she was receptive to mating.

Love….flehmen…a rose by any other name would smell as sweet…..

Until next month….m

Nikon D500, Nikon 200-400 mm @ 310 mm, effective 450 mm), f/4, 1/640s, ISO 560, +0.5 EV

Sources:

What is the flehmen response and why is it used?

31

Shot of the Month – August 2019

This month we visit with a dandy of a duck — America’s own Wood Duck. The male is supremely colored (per usual) — his head is adorned with an iridescent green and maroon crest while his face is deep purple with white stripes. He also has a red bill, with another white stripe with a jazzy yellow patch at the base. And that glorious red eye (ok, well, two red eyes). But there is more Johnny! His chest and rump are dark red while his back and wings are a shimmering dark blue-green. There is even more, just check out the images to see it all — the drake wood duck is a paint-by-numbers dream come true!

Of course all of this fancy dress is to attract the ladies — lady ducks that is. These colors do not last year round however — once the breeding season is over, usually by early summer, the colors fade until next mating season. In late summer the male grows gray feathers with blue markings. The female wood ducks are much more humble in their coloration — they have gray-crested heads (no one ever said, “Oh look – Gray!!”), and generally covered in splotches of brown, gray-brown, and some white. This coloration is quite sensible as it helps the females draw less attention to themselves and the chicks. “Blah” is much better for blending and avoiding getting eaten. Just sayin….

Woodies are cavity nesters — the female lays her eggs in an existing hole found in a tree. This sounds like a reasonable plan till you realize that these holes are usually about 30 feet above the ground. How do the chicks get down? Elevator? Nope. One day after the eggs hatch the female leaves the nest and goes to the ground and calls to her chicks. The chicks respond with peeping calls and climb up to the entrance of the hole and launch themselves outward to the ground. Wow!

Check out this video to get a sense of how crazy this is. (This video is of Mandarin chicks, but the idea is exactly the same).

Once they are all out mom leads the ducklings to water. The female stays with the chicks and tries to keep them safe but does not feed them. The ducklings are able to feed themselves from day one. After about 8-10 weeks the chicks are fully feathered and can fly.

Interestingly, the diet of wood ducks changes as they get older. As ducklings woodies dine primarily on aquatic insects. As they grow to adults they shift over to a plant diet eating mainly aquatic plants, nuts and seeds. Favorite food for a wood duck? Acorns!! Who knew??!! In fact wood ducks have an expandable esophagus that allow them to swallow multiple acorns — one woodie was found with 30 acorns in his throat!

For those keeping score at home, wood ducks are “dabbling” ducks – dabbling ducks place their head under water while looking for food as their butts and feet stick up in the air. Other dabblers include mallards, northern pintails and green and blue-winged teals. Alternatively there are diving ducks, which well, you guessed it, dive and submerge completely below the surface of the water.

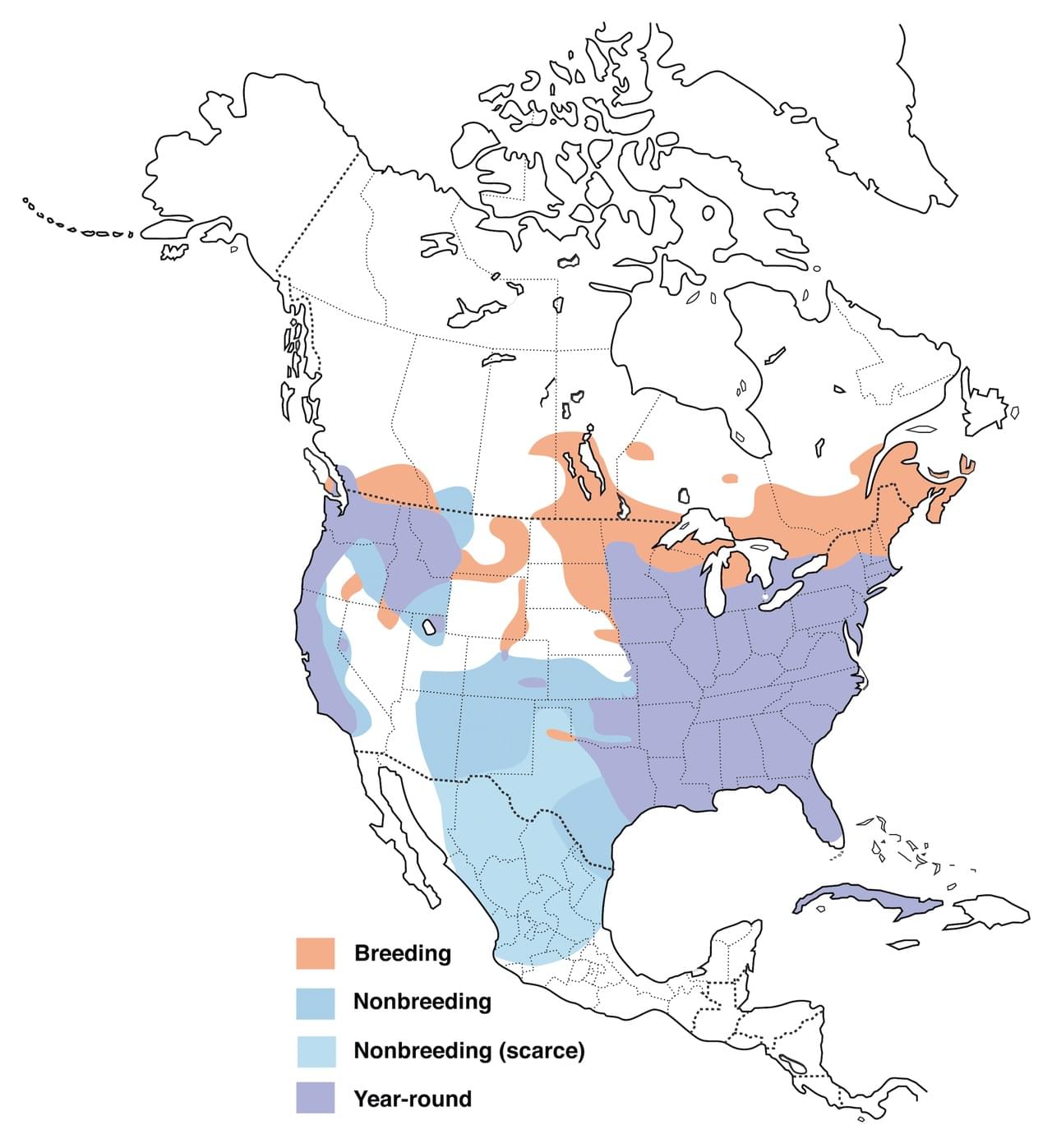

Wood ducks are, unusually for ducks, built for arboreal life as well as for life on the water. Their feet are not only webbed, normal for a duck, but also have sharp claws, not so normal, which facilitate perching on tree branches. The wings of wood ducks are also more broad than other ducks to make them more adept at twisting and turning in flight which is handy when navigating tight places between branches. Woodies are most at home in wooded wetlands and along slow-moving, tree-lined rivers. The don’t like open water. Look for wood ducks around the edges of swamps, sluggish streams, overgrown beaver ponds, and wood-fringed marshes. Check out the map below to find an acorn duck near you.

Wood Duck Range Map (Source)

And speaking of odd names, other aliases for the wood duck include summer duck, woodie, Carolina duck, swamp duck and squealer (they can be noisy).

I have to say that I still find it odd to be out walking in the woods and look up to find a wood duck perched on a branch — just don’t seem right. A duck. In a tree. One that eats acorns, no less. Sounds like a bizarre duck/squirrel experiment gone horribly, albeit beautifully, wrong. Oh well, get out there and find yourself an acorn duck – they are a wonderful sight to behold.

Until next month….m

Sources

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm w/ 1.4x TC (850 mm, effective 1275mm), 1/800 sec, f/5.6, ISO 400

30

Shot of the Month – June 2019

This month a photo of a tulip that demonstrates the power of isolating your subject to help create a compelling image. In this shot there is no doubt about what this photo is about — our eyes can’t help but be drawn to that lone red tulip in the center of the frame. In this image I used several techniques to isolate the subject:

Choice of depth of field

In this shot I used a very shallow depth of field (aperture of f/5.6) to ensure that almost all of the other flowers in this field were out of focus. Our eyes are naturally drawn to the part of the image that is in focus. For comparison look at the same image taken with a very wide depth of field (aperture of f/22). In this version  the field of flowers is more in focus and, at least for me, more distracting. I find that my eye jumps around more from one part of the photo to the next and weakens the visual impact. Click on the image to see it larger. Here is a primer on understanding depth of field.

the field of flowers is more in focus and, at least for me, more distracting. I find that my eye jumps around more from one part of the photo to the next and weakens the visual impact. Click on the image to see it larger. Here is a primer on understanding depth of field.

Point of View (POV)

To get this image I shot while crouched on my knees to get a low angle — this allowed me to shoot up and through the red flowers in the foreground and create depth in the image. This POV also allowed the red tulip to appear higher into the field of purple in the background and helped create more separation and space between the subject (red) and the foreground (red). Don’t be afraid to move around and explore the scene to make sure you are including the elements you want in the shot, and perhaps even more importantly, explore how your POV can help remove elements that weaken your image. Try higher. Then lower. Move to the right. To the left….shake it all about….

Contrasting Color

I was immediately drawn to this scene by how the red tulip popped visually against that purple background. The lovely green stem of the subject also adds more contrast and leads the eye to the subject.

Centered Subject

While it is often not recommended to center your subject it can sometimes be a useful technique under the right circumstances (See my post here on this topic). I usually try multiple compositions with the subject to the left, right and centered to help find what works best for the scene. I also often shoot in both landscape and portrait orientation to see which leads to a stronger composition. Given the vertical nature of the flowers portrait orientation worked best.

Wow, so much to consider to just get a pretty picture of a flower! These are in fact just a few of the ways that one can isolate the subject of an image. What are the others? Hmmn, that sounds like fodder for a future post….I just need to get outside and get the shot….stay tuned.

Until next month…m

31

Shot of the Month – May 2019

This month we visit with the glorious Selasphorus rufus, aka the Rufous Hummingbird. For those of you who are a bit rusty on your color palette (I was):

Rufous: reddish brown in color.

So while the name is not terribly creative it is accurate. The male Rufous is adorned in reddish brown on the crown, tail and sides. His back can be rufous, green or a bit of both. But the pièce de résistance for the male is that flame-orange gorget. Gor-what? It is a term that refers to the piece of armor that knights wore to protect their throats. It now refers to the patch of color that can be found on a bird or animal. The intense glint of the gorget is the result of iridescence, rather than colored pigments. The bird’s throat feathers contain minutely thin, film-like layers of “platelets,” set like tiles in a mosaic against a darker background. Light waves reflect and refract off the mosaic, creating color in the manner of sun glinting off oily film on water. The color and intensity of the gorget changes depending on your angle of view. (Source) The female Rufous is not nearly as flashy — she typically is greenish above with rusty-washed flanks, rusty patches on her green tail with a spot of orange on her throat. (Source)

In researching the Rufous I was surprised to see how often the word “fiesty” came up. One article said that the bird was “well known to be incredibly feisty and pugnacious.” As far as hummingbirds go the Rufous is considered to be on the small side, usually between 2.8 to 3.5 inches and weighing about 3.5 grams. For comparison a US penny weighs about 2.5 grams! Apparently no one told the Rufous — they are commonly considered the most aggressive of the hummingbird species! As one literary-minded observer noted:

“The male Rufous, glowing like a new copper penny, often defends a patch of flowers in a mountain meadow, vigorously chasing away all intruders (including larger birds).” (Source)

Ever have a Rufous at your backyard hummingbird feeder? Yikes — I can tell you from personal experience that they defend those feeders with equal zeal. They drive off other hummingbirds, bees, wasps, birds and other insects without respite. I had one hover 2 inches from my face trying to scare me off. We eventually set up more feeders around the house to try and give the other hummingbirds a chance at some food.

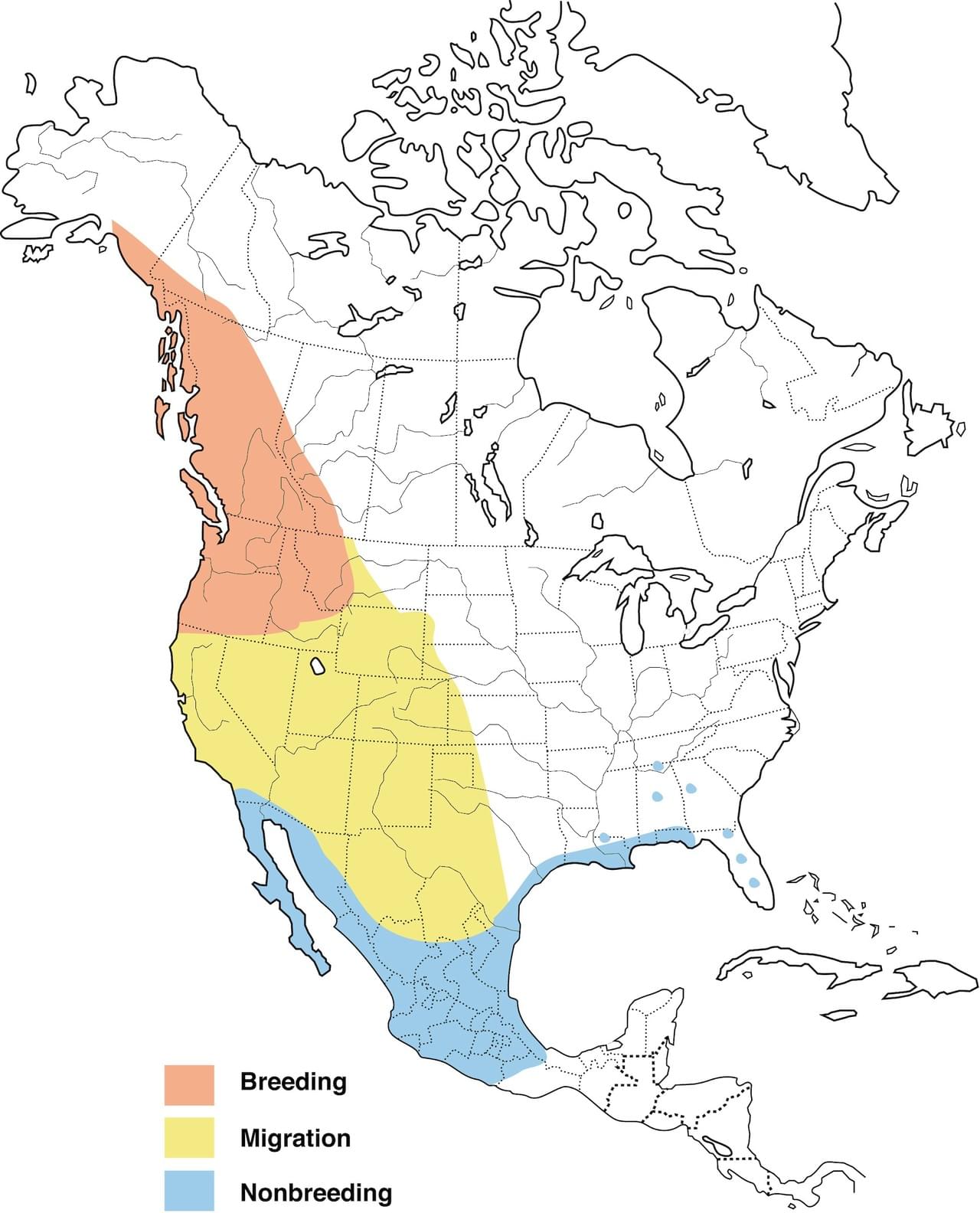

Rufous Hummingbird Range (Source)

Like other hummingbirds the mainstay of their diet is protein and sugar. They get their sugar by feeding on the nectar from colorful, tubular flowers which they access with their long extendable tongues. Preferred flowers include columbine, scarlet gilla, penstemon, indian paintbrush, mints, lilies, fireweeds, larkspurs, currants, and heaths. The flying pennies get their protein and fat by catching insects like gnats, midges and flies in the air. They will take aphids off of plants also. Given their frenetic lifestyle they consume three times their body weight in food each day. The Rufous has a fantastic memory that helps it find flowers and feeders along its long migration route from previous years. (Source)

Speaking of which, the Rufous hummingbird has the longest migration of any hummingbird — they can fly up to more than 2,000 miles in one direction from the northwest United States down to Mexico and the Gulf Coast where they winter. While the Rufous hummingbird is found predominantly in the western US this far ranging bird has been spotted in every state except Hawaii. These guys get around!!

I can’t help but admire this little bird — the Rufous is a real beauty to behold, is a tremendous athlete, has a sharp mind, and has the fighting spirit of a heavy weight boxer – all rolled up into a thimble-size body!

Until next month…..michael

Nikon D500, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/500 sec, ISO 400, -0.333 EV

30

Shot of the Month – April 2019

This month we visit with the most powerful cat in the Western Hemisphere — the Jaguar. This heavyweight of the feline world is the third largest in the world, coming in just behind the Lion and then the Tiger. The jaguar is the only member of the “Big Cats” that is found in the Americas. I photographed this jaguar in the Pantanal, in Brazil.

Looking like a heavyset leopard these cats are built for life in the tropical rain forest where they are found — they have muscular limbs and large paws which allow them to climb trees and swim rivers with ease. Unlike most felines, these cats absolutely love the water and rarely stray too far from the river. That being said, they are adaptable and can be found in other habitats including grasslands and deserts.

The jaguar is a stalk-and-ambush hunter unlike lion and cheetah which chase their prey. These cats walk slowly, and silently through the jungle in search of a meal. They also walk along the river’s edge, or even in the water as seen in my image above. We watched this impressive male, known locally as Mick Jaguar (Groan, I know. It doesn’t seem as corny when you are there seeing this incredible cat….) hunt along the river for several hours. Even though Mick is past his prime now, perhaps 11 years old, he is still the top cat in this part of the river. You can see that his one eye is injured but we were told that he can still see with it.

Medium-sized mammals make up the majority of Mick’s diet and can include deer, capybara, Peccaries, and Tapirs. When hunting in the water prey may include turtles, fish, and caiman (a relative of the crocodile and alligator). In total Mick and his brethren can take over 85 species depending on what they can find. One of the few jaguars that lived in the US was known to even kill and eat American black bears. (source)

Like most big cats Mick kills large prey with a deep throat bite that suffocates the animal. Jaguars have the most powerful bite of any cat and sometimes kill their prey by biting through the animal’s skull! When hunting large caiman the jaguar will sometimes jump on the back of the reptile and bite through the base of the skull and sever the cervical vertebrae which instantly paralyzes the animal.

Blah, blah, blah. So many words. Watch this unbelievable video of Mick himself on a hunt from several years ago– this video will show you everything you need to know about the hunting style of the jaguar, their fearless nature, and their lethal hunting techniques.

Any questions? WOW!

Until next month…..m

Want more?….

Check out my other post on the Jaguar.

And a few more videos:

A different angle of the same hunt as shown on National Geographic

And a short piece as shown on Nature about the Jaguar

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm f/4, 1/800 sec, ISO 250, +0.5 EV