15

Shot of the Month – March 2012

Iceberg? Huh? What iceberg? You know the one. I am talking about the “proverbial” hunk of ice that you hear so much about. And when people refer to said metaphorical ice flow, which part gets all the attention? Yes, exactly — the tip. As we learned in 5th grade science, only about 10% of the total volume of an iceberg is visible above the surface of water. That relatively small object that we see floating fails to convey the true scale and entirety of the object. We often use the phrase to indicate that we have not fully expressed or captured the scale of a problem.

“Jimmy, use the phrase in a sentence.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Climate change is making severe weather events more frequent and more intense. Yes, that is true, but that is just the tip of the iceberg.” (Jimmy, apparently, has a strong sense of irony also.)

Photographers, like me, rarely allow you to peer beneath the surface at what lies below. We deal almost exclusively at the very tipity tip of the iceberg. When we show you an image, if we are smart, we only share the best of the best of what we have captured. When you see an image on a website, in a magazine, at a gallery, on a card, or via whatever medium of choice, you are seeing the tip of the iceberg.

So, what lies beneath the surface? What makes up that massive pyramid on which this image rests? For a wildlife photographer, capturing a compelling image of a wild creature is stunningly difficult. For a given “winner” shot there can be thousands of images that didn’t work. Too dark. Too blurry. A branch in the way. The light too harsh. Light is too dull. Boring composition. Too far away. Too close. The damn thing blinked. It looked away. It ran away. It flew away. The shutter speed was wrong. Wrong aperture setting. Used the wrong white balance. Too much grain. Got a picture. Could show you, but I never would. Too embarrassing. Didn’t work. Too much…too little…just too ________.

That is a big part of the iceberg.

Another part of that iceberg, that you never see, is a massive space of — nothingness. Never even got a picture. Finding wildlife is HARD. Many hours are spent looking. Driving. Walking. Sitting. Seeing, nothing. Of course, the more elusive the animal, the more I want to photograph it. That is my curse, my insanity.

There is an Audubon wildlife area near where I am living here in Vermont. I have gone about a half dozen times over the last year. I have yet to get a single usable photo. There is nothing unusual about that — that is expected. This weekend we went to explore a new area in the NorthEast Kingdom — we hiked for three hours. A nice walk through the forest. A lovely day spent, far, far below the surface of the water. I took a few shots of a very small bird, that was very far away, into the sun. File, delete.

Since moving to the upper northeastern part of the US last year I decided that one of my goals would be to get a good shot of a Snowy Owl. I have never lived far enough north previously to make this a feasible venture. That was my winter project (and will be for the next several years). Given that I do have a day job and various family and social responsibilities, the time for this project was limited. I managed to get out on three weekends. For two of those trips I traveled to Parker River National Wildlife Refuge — seems that most years a few Snowies come down from the Arctic to spend the winter at this coastline park.

I was very lucky in that I did see Snowies almost every day. Here is the best shot I have so far.

This is not a shot I would display publicly.

(I actually feel a little queasy).

It is an OK shot. But the light was weak. The bird was quite far away for my lens. I had to use a very high ISO setting (Remember ASA ratings for film? This is the digital equivalent) to make an exposure. So to create this image I had to crop the photo significantly, but that high ISO then caused the image to be very grainy.

Unacceptable for public consumption.

Other shots from the depths? (click on an image to see it larger)

You will find no shots of Snowy Owls on my website. Not yet. This iceberg is a work in progress.

There are many similar blank spots on my site.

My spring project is Wood Ducks….wish me luck.

Stay tuned, hopefully towering icebergs are on the horizon.

All the best…michael

15

Shot of the Month – February 2012

They say that a picture is worth a thousand words, implying that a photo can often much more richly convey the action, the emotion or the beauty of a scene than can a narrative. This month I fear that both images and prose alike will fail to capture the spell-bounding ten minutes we spent watching this green heron hunt for fish in a shallow puddle in Botswana. I realize that it sounds absurd, but this heron put on a show that was as captivating as any lion kill that I have seen.

How could this be so? It was like watching a Kung Fu master – the intensity of his gaze was mesmerizing. Stalking through the shallow water his body would go rigid, as he lowered into a tense crouch. As he stood there like a ninja warrior, the anticipation was nearly unbearable.

(Imagine the cat-like shrill noise that Bruce Lee would make…)

Wait for it…..

Strike a pose. Kapow! Another fish. Here we see only 2 of the 20.

We weren’t the only ones to take notice of this impressive display.

This Pied Kingfisher was watching the show from a nearby branch. He was so outraged that the heron was catching all “his” fish that here we see him leaping from the branch as he dive-bombed the green heron. The heron simply ducked (you would expect nothing less from a ninja heron) and he continued obliterating the fish population.

Yes, little fishies, the legends are true. Green Heron Ninjas are real. And should one, perchance, happen upon your little puddle, be afraid.

Be very, very afraid.

Until next month….

15

Shot of the Month – January 2012

Talk about truth in advertising – “warthog” pretty much sums it up. There really is no way around it, these pigs are, well, not pretty. In fact, they are so unattractive that many find them adorable.

This photo, taken in Botswana, does a pretty good job of highlighting a few of the warthog’s most notable attributes.

First, there are the namesake warts. There are two, one on each side of the head, near the eyes, and two more just above the nose. These protrusions have two roles. The first makes some sense – they act as armor to help protect the pig when fighting or trying to fend off a predator. The second is a bit of a shocker. Those protrusions are fat reserves. Turns out that warthogs do not have subcutaneous fat – so it is true that they are not beauty queens, but they can gloat about their low body fat.

Second, we have those tusks. The ones on top are impressive, but it is the smaller bottom pair that is most dangerous. The bottom set of ivory becomes razor sharp as it rubs against the upper set of tusks each time the warthog opens and closes his mouth. Together these four tusks represent a serious threat and warthogs have even been known to kill lions with these weapons when lashing out in self-defense (more the exception than the rule, but still impressive…)

And last, the famous warthog tail, seen here pointing at roughly 10 o’clock. When fleeing that tail points straight up like a flag signaling “Retreat!” Ask anyone lucky enough to have gone on an African safari to list off some of their favorite memories – “warthog running with its tail up” is a safe bet to be among the top three.

The warthog, a creature that is so hard to look at that you can’t help but stare.

(and admire…and smile…)

15

Shot of the Month – December 2011

Woodpeckers are the avian jackhammers of the wild. When at work, looking for food, or building a new home, their telltale sound is unmistakable. Rat-a-tat-tat. Rat-a-tat-tat. Rat-a-tat-tat. Rat-a-tat-ouch–that-makes-my-head-hurt-just-thinking-about-it. Tat.

There are about 200 species of woodpeckers distributed around the world, though oddly, none are to be found in Australia. I photographed this Golden-tailed woodpecker in Botswana. This African species can be found across much of Southern Africa and in some isolated pockets of East Africa.

On a given day a woodpecker may strike a tree with his beak 8,000 to 12,000 times (up to 20 times/second). With each blow, the woodpecker experiences 1200 g of force. Is that a lot? For reference, humans pass out at 4 to 6 g’s of force. We get a concussion with a deceleration of about 100 g. (Geek Note: One g is the acceleration due to gravity at the Earth’s surface and is the standard gravity (symbol: gn), defined as 9.80665 meters per second squared, or equivalently 9.80665 newtons of force per kilogram of mass. Yawn)

How exactly do woodpeckers move around so easily in the trees and do what they do without knocking themselves out? Seems that woodpeckers have developed some nifty adaptations:

Avoiding Brain Damage (always a good idea)

- Thick Skull: Woodpeckers have a thick skull with spongy cartilage at the base of their beak. This spongy base absorbs much of the force.

- Strong Muscles: Woodpeckers have developed very strong muscles that attach the upper and lower jaws to the skull. By contracting these muscles a millisecond before contact the woodpecker diverts some of the impact to the base and rear of the skull.

- Accurate Strike: The woodpecker does a very good job of whacking (yes, that is the technical term for it) his target at a very precise ninety degrees. This perpendicular strike reduces torque which could cause a concussion.

- Small Brain: Woodpeckers have relatively small brains for birds of their size. The small ratio of brain weight to brain surface area allows for the impact to be spread over a large area, reducing the risk of damage.

Hmmn, thick-skulled and small-brained…make your own joke here ____________

Other nifty adaptations:

- Safety goggles: Just before contact a nictitating membrane (a transparent third eyelid) closes, protecting the eye of the woodpecker from flying wood chips. This membrane also acts like a seatbelt holding the eye in place – given the tremendous deceleration of the head the bird’s eye could literally pop out without this extra support.

- Kick Stand: Woodpeckers have a stiffened tail that is useful for climbing and foraging. They can use the tail as a prop.

- Knarly feet: Woodpeckers have zygodactyl feet, allowing them to walk up a tree easily. If you look closely at the image you can see these feet in action. Zygodactyl feet have 2 toes that point straight forward and 2 that point backward.

The wondrous woodpecker. Probably not the bird to call if you need help with your homework, but definitely look him up if you want help remodeling the kitchen.

Until next month… 🙂

15

Shot of the Month – November 2011

This month we visit with one groovy, chillin canine – a Black-backed Jackal (BBJ) sitting in the sun in the Kalahari Desert in Botswana. Look closely at his face. His serenity appears sublime.

I have seen many black-backed jackals and such moments are rare. More typically I have seen them, usually two, as they tend to form life-long partnerships, scampering along with great purpose. No time to spare. Looking for the next meal. Perhaps hurrying home to feed the pups. Other times scampering to avoid danger from a leopard or other predator. Occasionally a restive jackal, but more often than not — scampering.

BBJs are cunning and exceptionally quick. They can dash in and steal a morsel of food before a dining lion has noticed what happened. Ok, that is quick, but these guys are QUICK. Our guide Simon told us about the time he was asked to help sedate a few jackals with a dart so a local scientist could take some measurements. For this exercise, they had to use blow guns to deliver the darts as a rifle would generate too much force on a canine that only weighs about 20 pounds.

Simon loaded the long tube, found his target, and fired. Pfffft. And the dart was off – faster than anything you or I could see. The jackal, hearing the sound, looked over and at the last instant, scooted his butt out of the way and seemed to watch the dart as it flew by. Ok, lucky move. Reload.

Pffft.

Again, at the last moment, the jackal stepped aside like a matador as the raging bull dart missed its mark. (Is he the “One?”)

They never managed to dart a single jackal.

Life on the plains is rarely restive, nor predictable. Dozens of times over the years I have seen lions feeding at a kill – many of those times BBJs watched from a few feet away, waiting their turn at the scraps. The lions never seemed to notice, let alone care, except one time in Tanzania several years ago. We watched as the lions finished off a carcass and then sauntered off for a nap. A BBJ finally moved in for a snack. To my amazement, one of the lions got up and began to stalk the jackal. The jackal was unaware. The lion launched his attack, but the jackal, using the above-aforementioned quickness, managed to escape. But boy, was that one annoyed jackal. He barked up a storm in the direction of that lion as if some unwritten code had been violated.

Stalking lions. Dart-zinging humans. It’s a jungle out there. When scampering along in your own jungle, remember to seek out Zen moments like the one captured here where you can.

Let’s try. Oooommmm. Oooommmm. That’s right, stop and relax. Light a candle. Sit lotus style (if your joints will allow it). Deep breath. Clear your mind. Innnnnhaaaaale. Exhaaaaaaale.

If you get it right, the only sound you might hear is that of your soul catching its breath. (I’ll keep my eye on the lion for you…)

Until next month…

15

Shot of the Month – October 2011.

Is it just me or when you read the name of this antelope does it make you think of a bumper sticker that might look something like:

Yeah, ok. Probably just me.

(For those of you playing at home, the “beast” in my bumper sticker is Dr. Henry Philip “Hank” McCoy, the Beast from the X-men comics.)

I grant you that the hartebeest is a bit odd looking but the reviews out there are tough. One site said that hartebeests are “ungainly antelopes, readily identified by the combination of large shoulders, a sloping back, a glossy red-brown coat and smallish horns in both sexes.” Another commenter said that the hartebeest, “ …at first glance seems strangely put together and less elegant than other antelopes.” Yes, all true, but not something we really say in polite company.

The taxonomy of this grass eater is complicated as it seems to be for many animals. There are about 6 sub-species and 2 separate species of hartebeest spread out in generally isolated pockets across Africa.

Roll call:

Subspecies: (this might be a good time to break out your atlas)

- Bubal Hartebeest: They used to live in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Yes, used to. We killed the last one around 1923. (Extinct)

- Coke’s Hartebeest: Found in Kenya and Tanzania

- Lelwel Hartebeest: Found in Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda (Endangered)

- Western Hartebeest: Found in limited numbers in West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo.

- Swayne’s Hartebeest: Ethiopia (Endangered); Somalia (Extirpated)

- Tora Hartebeest: Found in Eritrea and Ethiopia (Critically Endangered); Sudan (Extirpated)

Separate Species:

- Red Hartebeest: Found in Namibia, Botswana, South Africa

- Lichtenstein’s Hartebeest: Found in Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe

I photographed this Red Hartebeest in the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park in Botswana.

So what is the difference between a species and sub-species? Animals from different subspecies (of the same species) are capable of inbreeding and producing fertile offspring. They usually don’t interbreed due to geographic isolation. For example, Coke’s Hartebeest, the most prevalent version found in Kenya and Tanzania, could breed with Swayne’s Hartebeest, found only in Ethiopia, but they don’t as their territories do not overlap and these antelope do not move around much.

I think the hartebeests have developed a bit of chip on their shoulder about what us humans have been saying about them. Time for a little payback from a Red Hartebeest. (Note: A male hartebeest can weigh up to 350 pounds).

Follow this link

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2oymHHyV1M

or watch here:

Ouch. How is that for elegance? Now that’s one badass even-toed ungulate.

Until next month…. J

15

Shot of the Month – September 2011

I never could really keep it straight in my head what the difference was between a stork, heron, egret, and, well, between just about any other tall and lanky feathered thing. I have just done a bunch of reading on the subject and I would like to say that it is now all perfectly clear. It isn’t. I have learned however that the whole naming-of-animals thing is a rather messy affair. Here is what I know.

There are 64 species of birds that are considered herons. We call some herons, others egrets, and the rest bitterns. But they are all herons.

I photographed this elegant heron in Botswana. Given that it is predominantly white we call it an egret, even though there is no real biological distinction between a heron and an egret. But if a heron is white, or has some decorative plume feathers, we usually call it an egret. For the record, this is the Great Egret, aka, Great White Egret. There are four sub-species of Great Egret spread across the globe with one in Europe, one in the Americas, another in Africa, and the fourth found in India, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

And what about bitterns? “ Webster says that they are “any of various small or medium-sized usually secretive herons.” LOL. Well, that sounds pretty scientific. Probably more useful for identification, bitterns tend to have shorter necks than most “typical” herons.

Another useful tidbit. Herons fly with their necks retracted as opposed to storks, ibises, and spoonbills which fly with fully elongated necks

And remember, when all else fails, “Look at that pretty bird” works just fine.

Until next month… 🙂

15

Shot of the Month – August 2011

No introduction is required for this fellow.

The tiger is one of the most widely recognized animals in the world. Humans have been mesmerized by this apex predator for thousands of years. You could spend a lifetime cataloging all the historical, mythological, religious, literary, and cultural references to the tiger.

The tiger is one of 12 Chinese zodiac animals. It is an earth symbol. Tigers are the national symbol for at least 6 countries and are found on many national flags. Tigers are an important symbol in Buddhism. Tigers play every sport you can imagine: the Detroit Tigers (baseball), the Balmain Tigers (Australian Rugby), the Sunipret Ice Tigers (German Hockey), the UANL Tigers (Mexcan soccer), and well, there are hundreds more. Elvis thought they played a bit rough and the “Eye of the Tiger” gave Survivor a #1 song in 1982. A tiger was an important character in The Jungle Book, was a buddy of Pooh, and a tiger was found on a lifeboat in the Life of Pi. Calvin’s best friend was a tiger and a tiger named Tony helped sell a lot of cereal. From cultural god to Wall Street hawker, the tiger has been voted, at least in one poll that included 73 countries, as the world’s favorite animal. Yes, even more popular than Lassie and her canine brethren.

Normally from here, I would attempt to beguile you with a host of fascinating facts and tidbits about the tiger’s amazing physical traits or abilities. Or regale you with the challenges and risks of getting this photo of a Bengal Tiger in Ranthambore National Park in India –there were a few.

But none of that matters. What matters is that you understand how completely and utterly we have destroyed a species that we seemingly love and admire so much. Take a marker and color in most of Asia on a map – a huge swath of the land mass of our planet. That is where tigers used to live. Now tape that map on the wall and throw 6 or 7 darts at that colored area. That will give you a sense of the space where tigers now have to live.

In 1900 there were 100,000 tigers in the wild. There are now around 3,000.

In just more than a lifetime 97% of tigers have been wiped off the planet. The Bali tiger went extinct in the 1940s. The central Asia tiger vanished in the 1970s. We killed the last tiger in Java in the 1980s. The South China Tiger was killed off in the 1990s (a few still exist in zoos). The six remaining subspecies are struggling to survive.

We are destroying the forest they need to live in. We hunt and kill them to make aphrodisiacs. We kill them to make coats.

Wow, imagine how we would treat the tiger if it wasn’t our “favorite” animal!

People are finally starting to notice. Leaders from the 13 countries where tigers still exist attended the Global Tiger Summit in St. Petersburg, Russia in late 2010 to launch a campaign to try and double the population of tigers by 2022. India has been working for quite a few years to try and protect its tigers from poaching and has been increasing the areas that are protected for tigers. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has been working tirelessly to raise awareness.

Unless we take action soon, tigers will become our favorite memory.

Want to do something to help? Click here for ideas from WWF on actions you can take.

15

Shot of the Month – July 2011

For five days and nights, our wooden boat worked its way up the Sekonyer River through the oppressive heat and pallor of the Kalamatan jungle on the Island of Borneo. (If you can remember Martin Sheen’s trip up the Nung River in the Cambodian Jungle in “Apocolypse Now” you will have a good sense of what the conditions were like – though, luckily, without the gunfire.)

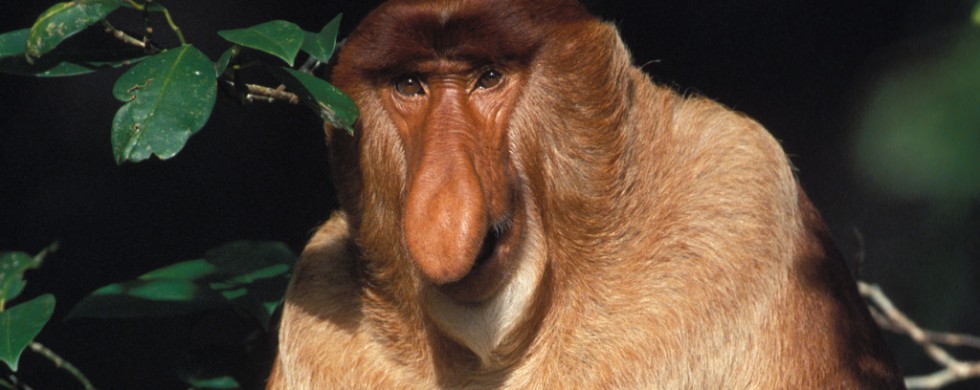

The primary goal of the trip was to see orangutans but along the way, we spotted this homely fellow, a Proboscis monkey, among the trees along the river’s edge.

Pro-what? New word for Michael. For you other non-scrabble players:

Proboscis: /proʊˈbɒsɪs/) an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate, e.g. the trunk of an elephant or the feeding tube of a butterfly.

Scientists aren’t sure but they assume that the larger the nose, the better the luck in attracting the lady monkeys. Go figure. The females also have largish noses but they are not as pronounced as in the males. Proboscis monkeys have the largest noses of any primates. The male vocalizes through the nose with a kee honk sound. Really, I couldn’t make this stuff up.

And a gentle reminder, it is not polite to stare.

Adding to the Homer Simpson look, the Proboscis monkey has a pot belly. Their stomachs are large to accommodate several compartments that use bacteria to digest the cellulose of the leaves of mangrove and pedada trees. When full, the stomach can represent 1/4th of the animal’s body weight! These leaves represent 95% of their diet.

Dining primarily on leaves allows the monkeys to remain safely high up in the trees and avoid predators lurking on the ground.

Proboscis monkeys are agile climbers but they are also quite at home in the water. They can often be spotted walking upright across stretches of water in the mangroves. Fishermen have even spotted the monkey swimming up to one mile offshore in the ocean. Proboscis monkeys actually have partially webbed feet – a testament to how much time they spend in or near the water.

In Indonesian (Borneo is part of Indonesia) this monkey is named orang belanda which means “Dutchman.” Seems the locals thought the Dutch, who colonized this part of the world, often had large noses and pot bellies like their local monkey. Sounds like payback if you ask me.

There you have it, the web-footed, pot-bellied, elephantine-esque primate otherwise known as the Proboscis monkey. Another beautiful, uh, well, striking sight from the natural world.

15

Shot of the Month – June 2011

This month we visit with the (Southern) Pale Chanting Goshawk (SPCG). Doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, does it?

I had never heard of such a bird and I was surprised when I first spotted this striking fellow while visiting the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana. SPCGs are distributed across southern Africa and prefer dry, open semi-desert environments. That would explain my lack of exposure to this fellow — I had not visited many southern African countries and I had explored even fewer game parks located in or near the deserts of these countries.

You can see in this lower photo the dapper marking of this raptor. Take note of the fine striped chest and leggings. His chest is an exquisite, delicate grey. And throw in a striking dash of color with those orange legs and black and orange beak. On several occasions, I almost injured my neck as I snapped my head around as my eyes were drawn to an orange beacon at the top of a tree or bush. Each time it was an SPCG. In the late afternoon light, already rich with hues of orange from the sun, his beak and legs seemed to glow with an other-worldly force.

SPCGs dine primarily on lizards, but will also eat small mammals, birds, and large insects. When hunting the SPCG will often land near his prey and then chase his victim down on foot.

It’s a ridiculous sight really, watching such a large bird sprint from here to there and back again like something out of a keystone cop film. The effect is even greater given that the bird is gussied up like some gangster from the 1940s. Throw in a pair of suspenders and his retro mobster look would be complete.

And who says that Mother Nature doesn’t have a sense of humor…?