31

Shot of the Month – January 2015

This month an image of one of Florida’s marquee birds. Now if you are not paying close attention you might think this is a shot of Florida’s renowned pink flamingo. Wading bird – Check. Pink plumage – Check. Florida – Check. But the giveaway that this is not a flamingo is in the bill. Check out the big spatula on Brad (pop culture reference). What we got here is a Roseate Spoonbill — Florida’s other pink bird.

This month an image of one of Florida’s marquee birds. Now if you are not paying close attention you might think this is a shot of Florida’s renowned pink flamingo. Wading bird – Check. Pink plumage – Check. Florida – Check. But the giveaway that this is not a flamingo is in the bill. Check out the big spatula on Brad (pop culture reference). What we got here is a Roseate Spoonbill — Florida’s other pink bird.

Myth Buster Alert: I, like most Americans I imagine, associate flamingos with Florida. Turns out that the American Flamingo does not breed in Florida and the occasional sighting is most likely that of a bird that escaped from captivity. In lower Florida, in the southern reaches of the Everglades, you may see a flamingo that is a vagrant from the Yucatan Peninsula. When Europeans first discovered Florida there was a small breeding population but that population either died off or migrated to other locations further south. So, despite all the flamingos in the souvenir shops, flamingos are not really part of Florida’s natural landscape. Wow, mind officially blown. (source)

But we are here to talk about a true Floridian — the Roseate Spoonbill. There are six species of spoonbill around the world and the Roseate is the only one that is pink. And it is the only one found in the Western Hemisphere. Roseate Spoonbills are typically found in Central and South America as far south as Argentina and Chile. They can also be found in the Bahamas, the Caribbean, and Cuba. In the US the breeding range is limited to coastal Texas, southwestern Louisiana, and Southern Florida. A popular place to see the Roseate Spoonbill is in Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge where I photographed this fellow.

The Roseate Spoonbill uses that signature bill to good use — it is a very effective tool for catching dinner. In the early morning and late afternoon the spoonbill can typically be seen wading through shallow water, head down, as it sweeps its bill from side to side near the bottom of the water with its mandibles slightly open. The bill has very sensitive nerves and will snap shut rapidly if prey is felt. Notice the two narrow slits near the top of the bill? They allow the bird to continue breathing even while the bill is submerged looking for prey. Pretty smart. Minnows comprise 85% of the spoonbill’s diet though they also eat shrimp, mollusks, frogs, newts, and some types of aquatic plants. Like flamingos, the spoonbill gets its pink color from the algae that is found in the crustaceans that the bird consumes.

Florida was almost left completely pink-free in the 1800s as the population was decimated by professional plume hunters to make hats and fans for stylish ladies of that era. By 1930 only 30-40 breeding pairs remained. Fortunately, action was taken and hunting of the bird was banned and special conservation areas were created to protect the bird. Since then the population has rebounded and about a thousand breeding pairs live in Florida. Today the main threat to the spoonbill is the loss of habitat as Florida continues to expand human settlements into coastal areas where spoonbills typically live.

Well, at least for the moment it is great news that the Roseate Spoonbill is literally, and figuratively, “in the pink.” (collective groan)

Until next month….m

Shot Information:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm w/ 1.4 x TC (effective 850 mm), f/5.6, 1/750s, ISO 200,

31

Shot of the Month – December 2014

The Pronghorn is a one-of-a-kind, American original. Though we sometimes call it the “Pronghorn Antelope” or “American Antelope,” and despite his looks, the Pronghorn is not an antelope. Pronghorns are the only surviving member of its family (Antilocapridae) and has no close relatives on this continent or any other. In case you were wondering, there are no antelopes in the New World.

The defining characteristic of the Pronghorn is its speed — it is the fastest land mammal in North America. We all know that the fastest animal in the world is the cheetah (see my write-up here). While difficult to measure the cheetah may be able to reach speeds up to 75 mph. The top speed for the Pronghorn is believed to top out around 53 mph. However, one could make an argument that the Pronghorn is the fastest animal alive. How so? Well, the cheetah can only maintain his top speed for a few hundred yards while the Pronghorn can reach 53 mph for a few hundred yards but then cruise at 30 mph for miles and miles. And miles. No other land mammal can keep up with the Pronghorn over a long distance.

The speedy nature of the Pronghorn is a bit of a mystery as none of its current predators, cougars, wolves, coyotes, or bobcats can run that fast. Some scientists posit that Pronghorns developed their speed in response to now-extinct predators like the American cheetah.

In the fall of 2014, I visited Yellowstone NP and spent some time among a herd of Pronghorn during the rut. I was able to see up close the explosive speed of the Pronghorn male as he would chase off rivals or corral errant females. I wanted to try and make an image that would convey the speed of the Pronghorn. Ironically, to demonstrate speed, the trick is to slow the camera down. I normally obsess about ensuring that I use proper technique and camera settings to allow for the sharpest images possible. For this image, I had to fight all my instincts and lower my shutter speeds to allow blur into the photo. I normally shoot with a shutter speed near 1/1000 of a second to stop the action and ensure razor sharpness; for this image, the shutter speed was 1/30 of a second. The key is to pan the camera at the same speed as the subject to try and keep it at least partially in focus while the background blurs with the motion. I experimented with shutter speeds of 1/15s, 1/30s, 1/45s, 1/60s, 1/90s, and 1/125s. The slower the shutter speed the more dramatic the effect. And all the harder to get something pleasing.

A few examples of how shutter speed can change the look of the image:

Here the shutter speed was 1/500s. Fast enough to completely stop the running Pronghorn. It is a decent photo but the image is oddly static given that it is a picture of a running animal.

Here the shutter speed was 1/125s. A bit of background blur is introduced while the Pronghorn is still quite sharp. Starting to get a sense of motion.

A shutter speed of 1/45s was used for this shot. More blur with the background and now the legs are starting to blur.

Here a shutter speed of 1/15s. The image is becoming more abstract.

I had a blast experimenting with the new approach and exploring new ways to communicate the story I was trying to tell. So, which image do you like best?

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm w/ 1.4x TC (850mm), 1/30s, f/11, ISO 200, +0.5 EV

30

Shot of the Month – November 2014

Course Title: Photography 101

Lecture #1: Composition

Rule #1: Never put your subject in the center of the image. (Yes, this will be on the final)

Ooops.

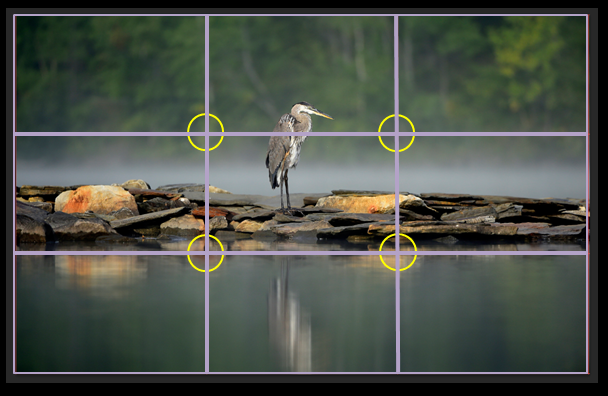

In the above photo I have broken a cardinal rule of photography composition — don’t put the subject of your photo in the center of the frame. Generally, photos with a dead-center subject tend to look too static, boring, dull — in a word, dead. I once read an article where the author recommended sticking a piece of masking tape in the center of the LCD screen on the back of your camera to make it hard to make that common error. It would look something like this:

It is generally recommended that you follow “The Rule of Thirds” (cue harp music). How does that work? Well, imagine two horizontal lines that divide your image into three equal parts. Next, add two vertical lines that break the image up into three equal parts. In the case of my photo, it would look like this:

To follow the rule of thirds you would align your subject along one of those four lines or at the intersection of those lines (shown by the yellow circles). If you are not sure how to compose the scene before you, start with the rule of thirds. Most cameras have a grid built into their display (check your manual folks) that you can turn on to help with composition.

To follow the rule of thirds you would align your subject along one of those four lines or at the intersection of those lines (shown by the yellow circles). If you are not sure how to compose the scene before you, start with the rule of thirds. Most cameras have a grid built into their display (check your manual folks) that you can turn on to help with composition.

I photographed the Blue Heron above from a kayak in Vermont over the summer. I took a variety of images, some closer, some further, some with the heron centered, others with him off to the left, then to the right. I oriented some in landscape and others in portrait. I really liked the color and texture of that narrow band of rocks and this centered composition allows the rocks to be the dominant element. For this scene, I think the symmetry works.

I have a similar image where I more closely followed the rule of thirds. But with that compositional change, I find that the heron becomes the dominant subject. A pleasing image, I think, but it tells a different story.

If we always followed the rules, life would be kinda boring, wouldn’t it? And all of our photos would look the same. Of course, there are no rules. A professional photographer told me once, “The only rule is that if it looks good, shoot it.”

Now that’s a rule I can live by.

Here is a fun video explaining the rule of thirds.

Until next month….michael

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm f/4 (@400mm), f/5.6, 1/1000, ISO 400

31

Shot of the Month – October 2014

I highly recommend that you check out the bugle concert series held in Yellowstone National Park each fall. To be honest, the music is really just so-so — the event is more operatic than philharmonic. But you will be spellbound just the same.

As the dawn sun fights its way up, through the chilled air the mountains surrounding us slowly ignite with color. Laden with tripods, cameras, and lenses we clamber over hill and dale in search of the best balcony seats to catch the show. We wonder when, even if, the event might start as we drive our hands deep into our coats to fight off the cold.

And then, at the edge of the sky, the silhouette of a 700-pound bull elk blocks out the light.

Dramatic entrance indeed. The melee begins.

Standing five feet at the shoulder, with another four feet and forty pounds of antlers the rogue towers over 9 feet tall. Wide-eyed, he thrusts his chest forward as he peers down on the hills and valley below. His body is an endless twitch as testosterone courses through him. The chemical transforms him into a maniacally focused beast. He is driven to conquer his rivals and win the right to pass on his genes.

The elk rut has begun. Each day over the next 4-6 weeks he will repeatedly bugle, unleashing a loud, screech of a wail to attract female herds and warn off other male suitors. It can be heard for miles.

During this period the bull will eat little, bugle often, and continually……endlessly…..relentlessly chase and test cows for their readiness to mate. Cow elks only come into estrus for 1-2 days so the male must be ever diligent. In a word — obsessive.

The dominant bulls will protect a harem of up to 20 cows from competing males and predators. When necessary, the bulls will fight. Rivals bugle at each other. If both are of similar size they approach.

Males may walk in parallel sizing each other up while trying to intimidate. If neither backs down then they lock antlers and wrastle it out. These fights are rarely fatal but they take their toll.

The bulls are frenetic, rarely relaxing even for a moment. Constantly watching over the herd. Endlessly chasing and scolding cows that dare wander too far. Warding off lesser males. I was exhausted just watching. During the rut, a bull can lose 20% of his body weight. After such a tremendous effort some bulls will not recover in time and will perish during the winter.

For two fortnights, the continual call to arms leaves some victorious, others vanquished. And for this observer, it left a memory made up of surely more than just sound, but also fury, firmly etched into my being.

The below video, shot in the Rocky Mountain National Park, gives a sense of the bugle boys in action.

Nikon D4S, Nikkor 600mm, 1.4x TC, (850 mm) f/5.6, 1/750 s, ISO 400, +0.5EV

25

Shot of the Month – September 2014

The Common Loon is the epitome of style and grace — most of the time. Loons spend most of their time on water and their bodies are exquisitely designed to make them powerful and effective swimmers and divers. Most birds have hollow bones while loon bones are solid. This extra weight enables loons to dive to depths of 250 feet in search of fish – the mainstay of their diet. They have large, powerful feet that propel the bird through the water like a torpedo. The bird’s feet are located unusually far back on the body which enable powerful underwater thrusts (imagine the avian version of Michael Phelps and his size 14 feet ). In the air loons are regal athletes that can fly hundreds of miles and reach speeds of more than 70 mph.

Now for some of those less stylish moments in loon life.

Loons have a very difficult time walking on land given the placement of their feet on their bodies. In fact, the name, “loon” most likely comes from either the Old English word lumme, meaning lummox or awkward person, or from the Scandinavian word lum, meaning lame or clumsy. Both of these names refer specifically to how loons look when hoofing it on land. To avoid such embarrassment loons rarely venture on terra firma except to nest and even then their nests are usually found only a few feet from the water’s edge to make for a short commute.

And while loons are powerful flyers they have a bit of a struggle in the transition up and down. Loons are unable to take off from land and on the water they need a long distance as they run across the surface building up momentum. Loons need anywhere from 30 yards to a quarter-mile of running and flapping before liftoff. In my photo above you can see those large feet in full force as he runs for the sky. The need for such space for takeoff means that you will never find a loon in a very small pond or lake as they do not provide enough of a runway for Loony Airlines.

And then there is the landing. Oh boy. Again, as the feet are so far backward loons are unable to land feet first like your typical bird. When they land on water they fly in head first and skim along on their bellies until they slow down. It is a sight to behold.

Incoming……. ……Outgoing

In their formal black and white dress and powerful moves, the common loon has a James Bond mystique. I have to admit a certain schadenfreude in knowing that these superstars also have their Mr. Bean moments like the rest of us.

Until next month…

Exposure:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm f/4 (@400mm), f/4.8, 1/1000 s, -0.5 EV, ISO 400

31

Shot of the Month – August 2014

If bird watching was like surfing, then in mid-to-late August wise birder dudes and dudettes would start paddling hard to catch the rising crest of the next big wave that is coming. (Click here for the appropriate soundtrack for this posting)

Birding? Surfing? Huh? Let me elaborate on my strained analogy.

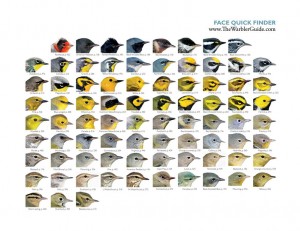

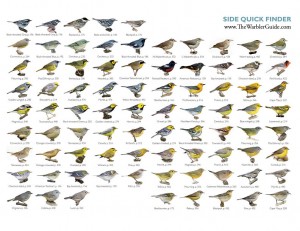

In late summer (if you are living in Vermont like me) or early fall if you are living further south, the fall migration of warblers is taking off (so to speak).

What’s a warbler? Well my dear non-ornithologically minded friend, warblers are a group of tiny (smaller than a sparrow), winged jewels of the bird world. In the New World we have about 113 species of warblers; of these 56 species can be found in the United States and Canada. Many of these fellows have striking colors and patterns. The visual treat is often fleeting as these guys are insectivores – they are always on the go darting from tree to tree, from leaf to limb, in search of the next bug to munch on. Trying to photograph these minute, energetic fellows is a recipe for hysteria as they flit hither and thither. By the time you snap the shutter they are gone (I have lots of shots of empty branches if you would like to buy one or ten). At best you tend to catch a glimpse of a wing, or a tail, or other assorted bird bits….

Back to the wave. The warbler diet requires that they stay on the move. There are no insects to feed on in areas that experience winter so warblers spend the cold months in Central or South America (the other 60 or so species of warblers live there year-round). This constant movement results in two glorious waves of warblers each year in the US — first there is the spring migration as the birds move north to their breeding sites; and then again in the fall as the birds head south before the chill sets in. The spring migration is a source of rapture for birders who have been suffering through long, mostly avian-free winter landscapes. The fall migration is also fun as it is like a lottery as you never quite know what migrant might stop by from one day to the next. This wave is bittersweet however as it is also a signal of the exodus of wildlife from the area for months to come.

Already by mid-August, we started to see the trees in our backyard come alive with shaking branches and flashes of color as warblers began to arrive. A bird may stick around a day or two but then they continue on their way. This wave will hit its peak in September and then the action will quickly fade away into October.

In the above photo, we have a Common Yellowthroat (CYT), the masked bandito of the warbler world. The CYT was one of the first warblers cataloged when a specimen in Maryland was recorded in 1766. I photographed this fellow in Baxter State Park in Maine. I made dozens and dozens of attempts to capture this guy before he finally sat in one spot long enough to get this image. While still numerous, the CYT population has been dropping by 1% per year since 1966 – so the population has declined 33% during this relatively short timeline (source). This trend is sadly, generally true for many songbirds across the US.

Here is a nice video of a CYT and a chance to hear his song:

Below is a quick guide on the breadth of warblers you might see. If you are really interested in learning more check out The Warbler Guide. It is an insanely detailed book on warblers and probably the definitive guide on identifying which bird is which.

Surfs Up! The crest is peaking as I write this. Grab your board, uh binoculars, and get out there and ride this colorful wave while you can.

Nikon D4S Nikon 600mm f/4; 1.4x TC (850 mm), f/5.6, 1/1000 s, ISO 2800

31

Shot of the Month – July 2014

This month a visual “snow cone” to help get you through the dog days of summer. As the sweat runs down your back, soak in this image and let the cooling begin.

Creating snow sculptures out of trees requires juuust the right sequence of weather events. First, you need a lot of snow. This image was taken at Targhee National Forest in Montana which is right next to Yellowstone National Park so the snow part was not too hard to come by in January, when this photo was captured.

Next, you need the temperatures to stay below freezing to keep the snow from melting. And lastly, you need the clouds to move off so you can have clear, blue skies.

Mother Nature smiled upon us and the elements all fell into place near the end of our one-week stay. On the last day of our trip, we climbed 9,000 feet to the top of Two Top Mountain and found this spectacular, Daliesque winter scene.

I have never seen a sky so Blue. Nor Whites, so white. As the morning sun rose, so did the temperatures, and the magic quickly began to melt away. But for a few hours, we had the fortune of visiting a special place that only exists, ever so briefly, when imagination and meteorology become one.

Until next month…michael

Nikon D4, Nikkor 70-200mm f/2.8 VRII (@ 78mm), f/16, 1/350s, ISO 200

30

Shot of the Month – June 2014

Whoever named the Red-winged Blackbird (RWB) didn’t take much time at the task. Sure, the name is accurate, but come on, really? By that measure, the American Robin would be called the Orange-bellied Thrush. Where’s the creativity?

Whoever named the Red-winged Blackbird (RWB) didn’t take much time at the task. Sure, the name is accurate, but come on, really? By that measure, the American Robin would be called the Orange-bellied Thrush. Where’s the creativity?

A more interesting nom de guerre perhaps? How about the Spartacus Swamp Sparrow? Yes, that has a certain ring to it.

Let’s Break it Down (Hammer style?):

Spartacus: RWBs are the gladiators of the cattails. During the breeding season, a male spends at least a quarter of the daylight hours defending his territory. Each day the male finds the highest nearby perch and rigorously calls out his claim on the surrounding little piece of the Earth as he provocatively flashes his red epaulets for all to see. (To be completely accurate, one must acknowledge that the epaulets often have a yellow or orange border)

Check out this video to hear and see one in action.

Females are attracted to the males with the brightest and biggest epaulets (hmmp, typical).

From his perch, the male aggressively defends the nest from all adversaries. These guys are known to take on animals, and certainly birds, much bigger than themselves as you can see here. This bald eagle apparently came too close to the RWB’s home turf and Spartacus came at him with a vengeance – I have a whole sequence of images of the RWB dive bombing and circling the eagle. Alas, the eagle never took notice of the robin-sized warrior.

Such an antagonistic attitude is well founded given the dangerous world RWBs live in. Just about every North American raptor preys on RWBs — short-tailed hawks are particularly fond of dining on them. Even barn owls who normally prey on small mammals are in on the take as are Northern Saw-whet Owls who are barely bigger than the RWB! Crows, ravens, magpies, and herons sometimes prey on blackbird nests. Other predators of the nest include raccoons, mink, foxes, and snakes. Marsh wren will destroy the eggs and peck the nestlings to death. You can see why RBWs have a chip, albeit a colorful one, on their shoulder.

Swamp: RWBs prefer wetlands and can live in both freshwater and saltwater marshes. That being said these guys are adaptable and can be found in just about any open grassy area and can even be found in dry upland areas where they will live in meadows, prairies, and old fields. They have a massive range and can be found as far north as southern Alaska and as far south as the Yucatan peninsula. Those living in the north will migrate to the southern US and Central America in the winter.

Sparrow: RWBs are not really in the same family as sparrows – I took some artistic, alliterative license with that one. In my defense, however, the female RWB looks like a large sparrow. The bland colors of the female allow it to blend in nicely and not draw any undue attention to the nest.

Given the relentless onslaught from predators and rivals, from both land and air, one has to admire the plucky Red-winged Blackbird. In my book, he has definitely earned his stripes.

Until next month….m

31

Shot of the Month – May 2014

Having moved to Vermont a few years ago I knew that one of my photo projects would be to try and get a decent image of one the marquee mammals of the American Northeast – da moose. Such projects begin with desk research, or more accurately nowadays, Google search. I scoured the internet for images of moose to get a sense of what’s possible, the best places to go, when to go, and so forth and so on. I was surprised by how few, really interesting images that I could find. Moose are large, rather gangly, and brown (similar to my dilemma with elephants, err, large and gray). Moose are most active in the early morning or late afternoon so the light can often be very dark, which is not good when your subject is already brown. A brown moose, standing still, in lackluster light. B-O-R-I-N-G. Fun to see in person, but not a recipe for a noteworthy photo.

The best images I found were either taken with a moose in water or with a moose captured among the fall colors.

Based on my findings I imagined the “ideal” shot — I wanted to get an image of a bull moose standing in the water (lake, pond, or river would do) with water cascading off his massive antlers with a mountain forest covered in glorious autumn colors as a backdrop. Piece of cake…

I learned that Maine was probably the best place to find moose in New England so I researched potential guides and called one to see if we could come to an arrangement. I described my ideal shot. The guide, admirable in his restraint, patiently explained why that combination of elements was pretty close to impossible.

What this flatlander boy didn’t realize was that Moose don’t have antlers year-round. Bull (male) moose grow antlers starting in the spring and reach maximum size in the fall — just in time to battle other bulls for the right to mate with cow (female) moose who are coming into season. With the rut over the antlers fall off at the beginning of winter as they are no longer needed and would be a huge burden (they can weigh 50 pounds) walking in the deep snow during a period when food is so scarce. During the summer moose feed heavily on aquatic plants that are rich in sodium. They will wade into a pond or lake and pull up lilies and pondweed. Some moose will even dive underwater to reach some plants.

So here’s the rub. Want big antlers and bright fall colors? Late September is the time to get that shot. Want to find a moose eating in the water? That happens during the summer, June-August. By the time fall colors have arrived, most water lilies and aquatic plants have stopped growing so it will be really, really hard to find a moose feeding on them at that time. Early in the summer moose can “regularly” be found in water dining but usually their antlers are fairly small and not fully developed.

So, there I was in Maine’s Baxter State Park, with low expectations on an otherwise lovely June day when this bull moose walked out into the pond and began to dunk his head for a meal. What he lacked in antler size he made up for in action. Every once and a while the moose would shake his head like a dog to shake the water off (Note: This was the ONLY moose I have seen do this). Just the extra element I needed to take a “nice” photo into the realm of something special.

Most of the time the moose was standing perpendicular to my position so I could not get the full effect. Mother Nature finally smiled upon me and the moose turned in my direction and decided to rinse off. I held the shutter button down and kept firing as long as I could. I instantly knew that I might have captured something special.

One may go many days, months, or even years in effort before those split-second opportunities flash by. But one of the greatest joys of photography, when successful, is that I can relieve that spectacular moment each day as I walk upstairs and pass by that image hanging on my wall. 🙂

Until next month…