31

Shot of the Month – March 2016

Fear not, this month I am not offering investment advice. Nor has my site been taken over by some spammer hoping to get you to invest in the latest “can’t miss” stock or some other illusionary fiduciary sinkhole. The Chickeree Trust Fund is an important investment strategy used by a mother to promote the success of her children — uh, squirrel children, that is.

Yes, a Chickeree is a squirrel, a Red Squirrel to be exact. They also go by Pine Squirrel, North American red squirrel, and boomers. The Chickeree moniker refers to the constant chattering or scolding you will receive from one of these squirrels if you walk into their territory. You can hear (and see) it here. The Red Squirrel can be found widely across North America wherever conifers are common.

They are one of the smallest squirrels in North America and only weigh 200-250 grams. (About as much as a roll of US nickels)

Chickerees primarily feed on the seed cones of hemlock, fir, spruce, and pine trees though they will also eat flowers, berries, bird eggs, tree sap, and sundry other morsels. These squirrels eat a variety of mushrooms – they will clip and gather truffles and hang them among the branches to dry in the sun (La-Dee-Da-Mister-Fancy-Pants squirrel…).

Now for the really interesting part — the trust fund.

Chickerees do not hibernate so they create caches of food known as “middens” to get them through the winter. Middens, found at the base of trees, usually consist of large piles of shredded cones and stems. The squirrels place green cones in the middle of the pile to keep them hidden and fresh. Red squirrels may have several stashes of food but they tend to have one main midden centrally located in their territory. The middens can grow in size over the years as the squirrel will often sit on the top of the pile as it feeds and the inedible parts of the cones will drop onto the pile (here is a picture of a large midden). These piles can be a few feet in height and 10 feet wide or more though most are 2 to 3 feet in width. A midden may contain 2,000 to 4,000 cones or up to 18,000 cones in the main midden. (Source)

In order to survive their first winter, a juvenile American red squirrel must acquire a territory and a midden. Some will go off and compete for a vacant territory. In some cases, the mother squirrel will grant part or all of her territory to an offspring. Sometimes the mother will create extra middens before giving birth and then she will bequeath these middens to her youngins.

Wow, how cool is that?

This behavior is known as “breeding dispersal” or “bequeathal” and is a form of maternal investment in offspring. This behavior seems to only occur in about 15% of litters and depends on the availability of food and the age of the mother squirrel.

There you have it, the amazing Chickeree — the tiny squirrel with the big heart.

Until next month….m

Nikon D4S, Nikkor 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), 1/180 s, f/8, ISO 400

29

Shot of the Month – February 2016

This month a serene swamp scene with the “Devil Bird.” No insult intended toward our fine feathered friend but that is what Anhinga means in the Brazilian Tupi Language — but I am sure that you knew that. The Anhinga is also known as the “Snake Bird” or the “Water Turkey.” What gives with all the nicknames? Well, each refers to different characteristics of this bird which is a type of darter. Darter? Sigh….so many things to learn in life. Darters are made up of 4 species of birds found in the Anhingidae family. The American darter, or Anhinga is found in the Western Hemisphere. The Oriental darter is found in Asia. You can guess where the African darter and Australian darter can be found, respectively. Zero points for creativity on the naming front.

This month a serene swamp scene with the “Devil Bird.” No insult intended toward our fine feathered friend but that is what Anhinga means in the Brazilian Tupi Language — but I am sure that you knew that. The Anhinga is also known as the “Snake Bird” or the “Water Turkey.” What gives with all the nicknames? Well, each refers to different characteristics of this bird which is a type of darter. Darter? Sigh….so many things to learn in life. Darters are made up of 4 species of birds found in the Anhingidae family. The American darter, or Anhinga is found in the Western Hemisphere. The Oriental darter is found in Asia. You can guess where the African darter and Australian darter can be found, respectively. Zero points for creativity on the naming front.

I photographed this Anhinga in Corkscrew Swamp in Florida. These birds prefer hot climates and their range includes the southern United States and extends south into Mexico, through Central America down to Argentina. (See a Range Map here)

So what gives with the Snake Bird reference? Anhingas are waterbirds that hunt for fish while swimming underwater or at the surface. They can dive quite deep as they have rather dense bones and their wings are not very waterproof so the soaked feathers help weigh the birds down reducing their buoyancy even more.

Like all darters, Anhingas use that sharp beak to spear fish. The devil bird is not a fast swimmer so its hunting style is more stalker than chaser. He mostly swims slowly underwater waiting for a fish to come near, then he impales the fish with a lightning-fast thrust of the beak. The neck is specially adapted for this kind of rapid thrust — the 8th and 9th cervical vertebrae create a hinge-like apparatus that allows for quick action. The bird usually stabs a fish through their sides with both mandibles open though he may just use the upper mandible for small fish. (Source)

That’s all very interesting, but I still haven’t explained the snake reference. OK, here is it. The Anhinga swims lower in the water than many birds due to its reduced buoyancy, a result of its dense bones and wetted plumage. When at the water’s surface, typically only the long neck and head are visible and the bird looks like a snake gliding across the water. Mystery solved.

Ok, and what about “Water Turkey?” Turns out that Anhingas lose heat quickly while in the water due to their lack of an insulating layer of body feathers. To deal with this they spend much of the day, like cormorants, perched on a snag with their wings spread and feathers fanned out to dry and raise their body temperature. Their wide, fanned-out tail reminds folks of another large, dark bird with a large tail — yep, da turkey.

Male Anhingas are glossy black and have silver patches on their wings. The female Anhinga looks similar though her head, neck, and upper chest tend to be pale gray or light brown. From this, we can see that we have a female snake bird in my swamp image. In the below image, we see a male Anhinga catching some rays.

There you have it, the American Darter, the shapeshifter of the swamp, aka, Anhinga, part turkey, part snake, and definitely the devil if you are a fish.

Until next month….m

Here is a good video on the Anhinga in action.

Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm (@ 380mm), f/4, 1/400 s, -0.5 EV, ISO 1100,

31

Shot of the Month – January 2016

If you just look quickly at this shot you might think, “Huh, nice goat thing” and move along. But if you look a bit closer you will see that we have a lovely mountain maternal moment going on here. See the dining lamb? Lower…..bingo, there you go.

If you just look quickly at this shot you might think, “Huh, nice goat thing” and move along. But if you look a bit closer you will see that we have a lovely mountain maternal moment going on here. See the dining lamb? Lower…..bingo, there you go.

As it turns out, the goat is actually a sheep, a Bighorn sheep to be exact. I photographed this one in Yellowstone NP. The name is a bit of a misnomer for the ewe as you can see that her horns are not all that big. As it often goes with species naming, the glory goes to the Y chromosome holder. The Bighorn males get all of the attention due to their massive horns and tendency to want to smash them into another ram to prove who’s the biggest and baddest ram in town. The last sheep standing gets the right to date all the cute ewes in the hood. It’s a dramatic show to be sure, but that is a story for another day.

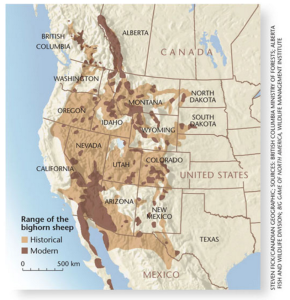

Bighorn sheep can be found in the mountainous regions of North America from southern Canada to Mexico. At the beginning of the 18th century, there were about 1.5 to 2 million bighorn sheep in North America. Then humans did what they do and by 1920 the sheep had been wiped out in Washington, Oregon, Texas, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and part of Mexico. So, in about 120 years the number of Bighorn Sheep dropped from a couple of million to a few thousand. There are about 70,000 sheep left on the continent now and about 400 Bighorn sheep remaining in Yellowstone NP. Sigh. (Source)

The map below shows the historical range of the sheep and their current locations.

The sheep were saved from extinction, in part, thanks to the efforts of the Arizona Boy Scouts. Major Frederick Russell Burnham, a famous conservationist and renowned “Father of Scouting” noticed that less than 150 sheep were remaining in Arizona in 1936 (I never heard of the guy but he had an amazing life. Learn more about him here). He called George Miller, the head of the scout movement in Arizona at the time, and told him that he wanted the scouts to save the sheep. What Fred wants, Fred gets — The scouts started a “Save the bighorns” poster campaign in schools across the state and other conservation groups joined the effort (i.e. The National Wildlife Federation, the Izaak Walton Foundation, and the National Audubon Society). These efforts led to the creation of two protected parks in Arizona and conservation efforts in other states began to improve the situation for the sheep. (Source)

Bighorn sheep are well adapted to life in the mountains and they can traverse ledges that are only 2 inches wide. Bighorn sheep are related to goats (you can certainly see the resemblance in my photo) and their split hooves make them quite sure-footed. The outer hooves are modified toenails that are shaped to snag any slight protrusion, while soft inner pads provide a good grip on uneven surfaces. In the winter the sheep descend to lower-elevation mountain pastures to find food and avoid the deep snow found higher up. During the summer the sheep will return to higher elevations to avoid the heat and predators typically found in the valleys (wolves, cougars, coyotes, bears, etc., oh my)

We almost pushed Bighorn Sheep off the evolutionary cliff but they have made a bit of a comeback thanks to recent conservation efforts. However, given the rising pressure from human encroachment, climate change, and poachers the future for these alpine sheep is still a cliff-hanger at best.

Until next month…..m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/5.6, 1/250 s, ISO 800

09

A couple of days ago I posted 10 of my favorite images from 2015. There were all color photos. Here is a sample of 10 of my favorite black and white images from 2015. Is that cheating?

This actually is a color photo that lacks color. This image was shot on a foggy, early morning pond looking into the sun. I love the back-lit water splash.

Another early morning shot. There was not much color to be seen at this hour and converting to B&W set a great mood.

I shot this photo with a point-and-shoot camera. I love the multi-layered, diagonal transition from pure white in the upper left corner to pure black in the lower right corner.

Harsh light when I shoot this image. But in B&W the image suddenly seems to become a timeless ode to familial love. (Its more an ode to hungry teenager, but let’s not ruin the moment…)

I like how this young moose really seems to pop in 3D with the different focal planes of the shot.

These birds were harshly back-lit and I almost didn’t take the shot. But then I realized what a great silhouette it would make. Glad I saw the light before it was too late….so to speak.

Another pair of courting waxwings. I shot this image while lying on the ground and supporting my 600 mm lens on my raised knees. I had to shoot through many layers of leaves and branches. I love the resulting effect. Stealing a secret moment among the trees…

Really harsh mid-day light. Converting to B&W really brings out the menace in this alligator.

I like the mixture of different hues and textures. A lovely dreamscape…

I like how the bird really pops against the background.

Bonus Images for making it to the end:

More loon love.

I love the color version of this image. I converted it to B&W on a whim and to my surprise I like this version very much also. The sky and ocean merge into one as the lighthouse beacons at the edge of the world.

03

It seems all the vogue with nature photographers these days to post their best shots from the previous year. I figured I would give it a go. Well, these are not all of my best shots but each is special to me for a range of reasons. I will provide a quick explanation for each image and why I chose it.

The images are not in order by preference. Please click on an image to see it larger (It is the best way to view them… :-))

#1 Fall Abstract

#1 Fall Abstract

Despite living in Vermont for the last 5 years I haven’t had much luck in getting good fall foliage shots. This year I had some great luck but I am most pleased with a series of shots where I experimented with a new technique (for me) that produced some nice abstract shots – to me they seem to really capture the explosion of color that happens here during this magical time in the Northeast.

I don’t shoot landscapes very often so my skills are pretty basic. This year I managed to spend only one full day in Acadia National Park but still managed to get this respectable shot. In this image I experimented with an HDR technique (I will explain this in a later post) that allowed me to capture the full dynamic range of the image. Another experiment that went surprisingly well!

2015 was the year of the Loon for me. After 4 years of trying I finally managed to get some very nice images of loon chicks riding on the adult’s back. The series of shots I got this year is definitely my best accomplishment of the year. (I still need to get these images on my website…)

I have never had much opportunity to photograph osprey diving for fish. This year I found an osprey family that lived near a fish hatchery and I was rewarded with a few new images to add to my portfolio.

I had never seen this stunning bird until we moved to Vermont. I also never had much luck in getting an image that came close to conveying how beautiful these birds are. This year my luck improved.

This year I finally got my first decent image of a calf moose with mom.

My final 4 shots are from a trip to Florida that I took in December. (I just got back a few days ago)

I was able to capture a nice collection of behavior shots of Blue Herons at a rookery in Venice, Florida. This couple displayed a fascinating range of courting rituals. Here we can see the male giving a stick as a gift to his partner. She will then add it to the nest that they were building for their new family.

#8 Roseate Spoonbill

I love this shot of a Roseate Spoonbill in flight.

I have always admired images like this where the background is all blacked out. I was able to experiment with this technique on the recent trip and I was pleased with a few of the images.

This lighting on this pelican is exquisite! The colors blow me away. Love it!

Bonus item for those making it to the end of this post:

#11 Moose Trip Video

This year I made my first video…not professional by any means but I think it does a good job of giving a sense of what it was like trying to photograph moose in Maine from a canoe.

Have a great 2016!

31

Shot of the Month – December 2015

Ok, their official name is Burrowing Owl (BO) but my title better captures how most people react to this pint-size beauty. I posted this image on my Facebook Photopage and the reaction was off the charts even though the photo is really just so-so in my opinion. That damn grass in the foreground!

Ok, their official name is Burrowing Owl (BO) but my title better captures how most people react to this pint-size beauty. I posted this image on my Facebook Photopage and the reaction was off the charts even though the photo is really just so-so in my opinion. That damn grass in the foreground!

Here we have a static bird staring at the lens in “just ok” light — but here is an example where excessive cuteness (owfully cute?) wins out over composition. And those EYES…I could get lost in there for days…..swoon…

While most birds spend most of their time in the trees, these owls, as you may have gleaned from their name, actually spend the majority of their time on the ground and live underground in, yep you guessed it, burrows.

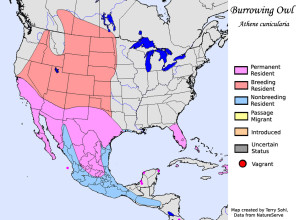

In the US, Florida is the only east coast location to see a Burrowing Owl. Otherwise, head west or south, and depending on the time of year, you can find them in Canada down through Mexico into Central America. Some species can also be found on various Caribbean Islands and others in parts of South America.

Historically BO’s prefer open prairies and cleared areas with short grass. In modern times they can be also found in pastures, farm fields, golf courses, airports, and vacant lots in residential areas. I actually photographed this fella in an empty lot in the suburbs of Cape Coral, Florida.

Florida BOs usually dig their own burrows, but those in the western part of the US typically use old burrows left by prairie dogs, ground squirrels, kangaroo rats, armadillos, or other animals. Burrows excavated by the owls may be up to 6-10′ long, with a nest chamber at the end.

Burrowing Owl Range (Source)

Burrowing Owls are some of the smallest owls in North America. These guys stand about 7-11 inches tall and weigh about 4-8 ounces. To give you a sense of scale, the BO is slightly larger than an American Robin!

Despite their small size these guys seem to have a Big sense of humor — did you notice the bird in the lower right corner of the picture?

Boom! Photobombed, baby!

Until next month….michael

Extended Range of Burrowing Owl (Source)

Nikon D4S, 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, 1400 ISO, +1 EV

30

Shot of the Month – November 2015

Could this be a wanted poster for one of nature’s craftier criminals? Or just a cute poster of a cuddly critter?

Could this be a wanted poster for one of nature’s craftier criminals? Or just a cute poster of a cuddly critter?

Just like a canine Jesse James, there is no shortage of tall tales that cast the fox’s character across the spectrum from saint to sinner and everything in between.

Regardless of your particular point of view, there is no disputing that humans are fascinated by this little fellow and use him as a foil for human fortitude and frailty alike.

Foxes got their first documented curtain call in 4 BC in Aesop’s fables in The Fox and the Grapes. Greek mythology engaged the Teumessian fox to devour children, and foxes appear in Celtic mythology as shapeshifters.

In Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (Kumiho) folklore foxes are powerful spirits that are known for their highly mischievous and cunning nature, often taking the form of female humans to seduce men.

In Arab folklore, the fox is weak and deceitful. In the Bible, the word “fox” is applied to false prophets (Ezekiel 13:4) and the hypocrisy of Herod Antipas (Luke 13:32). Foxes are very popular in Native American mythology and can be found in Achomawi, Yurok tribe, Inuit, and Menominee folk stories (But, you knew that…)

Our lexicon is riddled with foxy lingo.

- “fox/foxxy” = slang for someone with sex appeal

- “outfox” = means to beat in a competition of wits

- “vixen” = a female fox is called a vixen, it is also used to describe an attractive woman, though implies some questionable character traits…

- “shenanigan” = (as in deceitful confidence trick, or mischief) is derived from the Irish expression sionnachuighim, meaning “I play the fox”

In World War II, Erwin Rommel, the German commander in North Africa, was called the “Desert Fox” by his British adversaries, as a tribute to his operational cunning and skill.

I could go on and on. Foxes can be found on every continent except Antarctica and basically, just about every culture has assigned the fox archetype traits or powers. Foxes can be found in plays, novels, children’s books, TV shows, video games, movies, anime, music (Foxy Lady), opera, and well, just about everywhere. Go here to see an amazingly long and comprehensive list of all the cultural references through the ages.

Ahh, the crafty fox, the Dr. Who of the natural world….he is the lingua franca across countries, culture, time and space. And very cute.

Nikon D70, Nikkor 80-200 f/2.8 (@ 80mm), 1/1000s, ISO 200

31

Shot of the Month – October 2015

As you can see, the Rose-breasted Grosbeak (RBG) is a striking-looking fellow. And not only is he good-looking, this guy has a lovely voice. His double threat traits strike a chord with the ornithological crowd and stir flight of fancy and poetic prose.

As you can see, the Rose-breasted Grosbeak (RBG) is a striking-looking fellow. And not only is he good-looking, this guy has a lovely voice. His double threat traits strike a chord with the ornithological crowd and stir flight of fancy and poetic prose.

A few of my favorite turns of phrase:

“Bursting with black, white, and rose-red, male Rose-breasted Grosbeaks are like an exclamation mark in your binoculars.” (source)

Nicely done, sir. I love that visual.

Another, albeit a bit more gruesome nickname is “cut-throat.” I find that visual much less pleasing, though one can’t argue with the logic.

And for the bird’s lovely song? A couple of early twentieth-century naturalists said it is

“…so entrancingly beautiful that words cannot describe it….it has been compared to the finest efforts of the Robin and…the Scarlet Tanager, but it is far superior to either.”

Ouch, it seems that the robin and scarlet tanager will not be going to the next round of the competition.

Even the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (home of smarty-pants-bird geeks) was getting all artsy-like in its description of the RBG’s lovely fine voice:

“They sound like American Robins, but listen for an extra sweetness, as if the bird had operatic training…”

Operatic training? Oh, so high brow of them…

Here you can hear his lovely call in action:

If you want to catch this lovely star in action your best chance is to visit northeastern forests in the US and Canada during the spring and summer; the cut-throats spend the winter in Central and South America.

Ahh, the life of a celebrity…..until next month. 🙂

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm f/4 (@f/5.6), 1.4x TC, 1/2000 sec, ISO 800,

30

Shot of the Month – September 2015

I have taken liberty with what is perhaps Shakespeare’s most famous line to highlight the plight of one of humanity’s oldest partners — da bee. A recent study indicates that humans have benefited from the bee’s labor for at least 8,000 years. However, since 2006 or so bee populations have been crashing (Colony-Collapse Disorder (CCD) is the scientific lingo for it) around the planet and this beautiful relationship is in serious peril.

Why should we care?

Well, bees are expert pollinators and we rely on them to produce much of our food — some estimate that 1 in every 3 mouthfuls of the food you ate today was pollinated by a bee. Of the 100 crops that provide about 90% of the food eaten in 146 countries, 71% are bee-pollinated. Did you know that the ENTIRE almond crop in the US relies on bees for pollination? Me neither.

Without bees forget about apples, lemons, limes, carrots, celery, zucchini, oranges, blueberries, cherries, watermelons, grapefruit, lettuce, macadamia, cashew, coriander, cucumber, buckwheat, mango, avocado, apricot, peach, pear, raspberry, broccoli, onion…and many more. See a comprehensive list here.

Much of the pollinating is done by the Western Honey bee — a species that is commonly used by commercial beekeepers. Typically a beekeeper will lose about 10-15% of his bees over the winter. Since 2006 the loss rate has been around 30%. In 2014-2015 about 42% of all honey bee colonies died off.

So what is causing all the deaths? There is no single answer but most scientists believe the mass die-off is being caused by:

- Habitat Loss: Modern agriculture is characterized by massive fields with just one crop – rarely can you find a range of flowers along fields where bees can forage. These fields are like deserts for bees.

- Pesticides: Bees are very sensitive to pesticides and seem particularly sensitive to neonicotinoid pesticides. Neonicotinoids were introduced in the mid-1990s and bee numbers began falling soon after. Over 50,000 bumble bees (like the one I photographed here) died in Oregon in 2013 after a landscaping company sprayed nearby trees. Oregon banned the use of this insecticide in 2015.

- Parasites: A microscopic mite, the Varroa destructor, surfaced in the US in 1987 and has since killed millions of bees.

How can you help? A few ideas:

- Buy Organic: Organic farms don’t use pesticides.

- Buy Local: Support your local farms, especially local organic farms (see #1 above)

- Use less pesticides: We use WAY too much pesticides. Most pest problems can be solved without pesticides.

- Plant bee-friendly plants: Start a garden and provide desperately needed food for the bees. Here is some guidance on how to start. And check out this fun tool.

And here is a good list of ideas on how to help.

A world without bees would be terribly unbeecoming and a lot less beeautiful, and dining would be a lot more boring (damn, no “ee’s” in boring, sigh).

Anyways, we really do need bees to be, so do what you can to help out.

Until next month….:-)

Nikon D5100, VR Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8, f/10, 1/250 sec, ISO 200

31

Shot of the Month – August 2015

This month’s throwback pinup beauty is a gorgeous bison babe. I don’t know about you, but I find myself getting lost in those big brown eyes (Yes, I realize it is a black and white photo — trust me on this one). That luscious nose. And who wouldn’t want to run their fingers through that luxurious black hair?

This month’s throwback pinup beauty is a gorgeous bison babe. I don’t know about you, but I find myself getting lost in those big brown eyes (Yes, I realize it is a black and white photo — trust me on this one). That luscious nose. And who wouldn’t want to run their fingers through that luxurious black hair?

No doubt about it, that is a half-ton of cuteness right there. Bob the Bison would surely be humming Bob the Marley’s “Looking in your big brown eyes” as he sauntered by this bovine beauty.

The eyes come to life in this image because I was able to capture the elusive “catchlight.” Catchlight is simply the reflection of the sun or light source in the subject’s eyes. Catchlight adds depth and dimension to the eyes and makes the subject come alive. Wildlife photographers obsess about this little dint of illumination – some feel that the foundation of a great wildlife image is catching a bit of ocular sparkle.

Without the glint the human brain seems to not respond as strongly to an image — we tend to see the photo as “lifeless.” Sort of like the difference between looking at a photo of a stuffed toy bison and a picture of well, this Yellowstone beauty. That extra twinkle can make an otherwise “flat” image seem to jump off the page…errr, screen.

The eye glint thing also works for people. So when taking a picture of friends and family, try to capture a bit of catchlight to make your evil ____ more loveable/likable/humanlike. (fill in the blank with the relative or friend of your choice).

The psychological power of catchlight is so strong that sometimes in movies the director will go in the other direction and remove the glint from the eyes of antagonistic characters in post-production to make them seem more evil or heartless.

As you can see, beauty is truly in the eye of the beholder…..or is it the beholdee? Now I’m confused…

Until next month…..michael

Nikon D4s, Nikkor 600mm f/4G ED, 1.4x TC (@850mm), f/5.6, 1/750s, +0.5 EV, ISO 640